Tags

Aboriginal Peoples Family Accord, aboriginal title, Indigenous child welfare, Indigenous Peoples, Sovereignty

WARNING – this article refers to abuse of children

Two Indigenous people, a married couple, were sentenced on Friday June 23, the foster parents of young Indigenous siblings. They were charged with assault and manslaughter and sentenced to ten years in prison.

Our deepest condolences go to the children’s family, the perpetrators’ families, and the Sto:lo people in whose community these events – which are not unique – have unfolded.

That Sto:lo community is not alone, not in any part of this tragedy. The incomprehensible hurt and loss of innocent Indigenous children is part of a much larger, much older, ongoing and world-famous Canadian assault on Indigenous Peoples.

Another Indigenous mother presented her petition against British Columbia and Canada to an international arbiter, in 2007, for the senseless, routine, and indefensible apprehension of her children and their subsequent abuse in Ministry “care.”

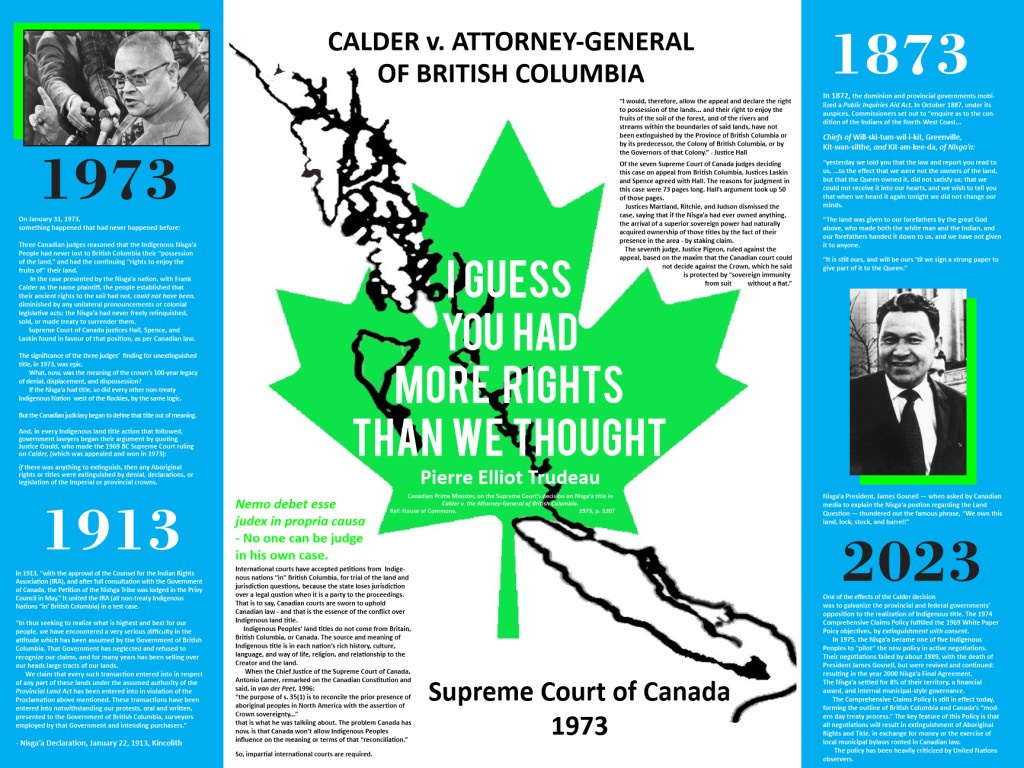

Her case was admitted to the Inter-American Court in 2014: not only do Indigenous Peoples suffer for a lack of jurisdiction over their own children and families, but they suffer from the total denial of their title and rights over everything else – their land and jurisdiction – that would allow them to maintain their children and families according to their own traditions.

That is, losing children to the state is the direct result of the state’s denial of Indigenous Peoples’ land titles and the accompanying rights, wealth, national identity, authentic governance, and social and cultural structures.

The Lake Errock case in the news

The First Nations Leadership Council has called for the resignation of the Minister of Child and Family Development, Mitzie Dean, and the Premier of BC snapped back that the Ministry has his full support and confidence. The BC Greens Caucus has now backed them up on the demand for a resignation.

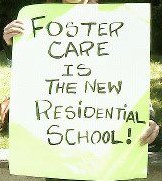

Are criminal charges pending against the Director of Child and Family Services of British Columbia? Children “in care” also died in 2020 and 2017 in BC. And 2015. And… the total lack of accountability or culpability in Indigenous child deaths “in care” is a signal from the colonial administration: they are only doing what they set out to do. This colony set out to supplant Indigenous Peoples, and the deaths of their children in mandated forcible removals is “just” a part of that mandate. It is no different from the “kill the Indian in the child” mandate established by the first Prime Minister of Canada, Sir John A. MacDonald, when he stated in 1910, “It is readily acknowledged that Indian children lose their natural resistance to illness by habitating so closely in these schools [Indian Residential Schools], and that they die at a much higher rate than in their villages. But this alone does not justify a change in the policy of this Department, which is being geared towards the final solution of our Indian Problem.”

Sixteen months after this eleven year old boy was killed in Lake Errock, by the foster mother, the Ministry’s culpability in the abuse and death is clearly a contributing factor. Seven months had passed since any agent of the Ministry, any social worker, checked the foster home or the children’s well being when the fatal events happened at the end of February 2021. There was not even a virtual check in by phone or online communication.

The trial has revealed that brutality was ongoing in that home, including coercing other children resident there to participate in abusing the 8 and 10 year old sister and brother.

While mainstream media is tip-toeing around the legendary mortality rate in Canada’s Indigenous child apprehension programs, there are some basic facts that we should be reminded of.

Aboriginal delegated agencies for children and families

There is, in British Columbia, a perpetual cycle of tragedy, inquiry, recommendation, ad hoc Indigenous involvement, delegated control capped by BC MCFD mandates, funding cuts, mismanagement, denial… tragedy, inquiry, recommendations…

The fact that this cycle has continued unchecked since the 1980s is proof positive of a mandate among BC social workers to disrupt and endanger young Indigenous families. Apprehension of children from young Aboriginal families, according to a career social worker who would rather not be named, is the unwritten but understood objective.

Indigenous communities have fought valiantly for the power to help their own families without interference. Indigenous Chiefs have rallied to several major commitments to step into roles of youth care and family support over the last four decades.

What they get is delegated powers from a colonial Ministry, which is perpetually determined to undervalue the cost of these responsibilities, and to control mandates and delivery.

The Indigenous foster parents of the two Indigenous foster children in this case were living in an area, Lake Errock, which is served by Xyolhemelh, a delegated Aboriginal child and family services society.

Xyolhemeylh is the agency that was responsible for Alex Gervais. In 2015, Gervais, age 17, died by falling out of an Abbotsford hotel room window where he had been “temporarily” housed by the society for 49 days.

The event was the subject of a February 2017 report on the dysfunction of B.C.’s Aboriginal child welfare system.

A press statement from the BC General Employees Union in 2017 explained:

“The Ministry of Children and Family Development (MCFD) is responsible for providing funding for a significant portion of the services that delegated Aboriginal agencies like Xyolhemeylh provide. A recent agreement between MCFD and the agency has brought caseload funding on par with levels within the MCFD, providing some relief from a dire recruitment and retention crisis at Xyolhemeylh.

“However, because MCFD has itself been drastically under-resourced for decades, the increase still isn’t enough to provide care that is appropriate to Aboriginal children and youth. “Unfortunately, staffing resources equal to MCFD is no answer for Xyolhemeylh workers who are desperately trying to provide services in culturally appropriate ways to children whose families are scarred with multigenerational trauma, and the dire poverty that so often accompanies it,” said BCGEU President Stephanie Smith.”

The cycle

The report, “Skye’s Legacy: A Focus on Belonging,” was submitted by B.C. Representative for Children and Youth Dr. Jennifer Charlesworth, explored the life of a youth named Skye, who died of an overdose on her 17th birthday in August 2017.

The report found that B.C.’s child welfare system left Skye without a sense of belonging, particularly as an Indigenous person, which contributed to her death. She was taken from her mother at age five and lived in fifteen different homes before her death twelve years later.

“Collaboration among ministry, Indigenous communities needed to assess living situations of kids in care: jury.” This headline refers to the death of a 17-year-old Cree teen in a group home in Abbotsford. The report recommended more family-based services for children in care and faster action when those children go missing.

Traevon Chalifoux-Desjarlais was found dead in a bedroom closet in September 2020, four days after he was first reported missing by a group home staffer.

The Timeline

2023, June 29 – The B.C. Green Caucus stands with the FNLC, calling for the resignation of Minister of Children and Family Development, Mitzi Dean, in light of the shocking and horrific systemic failures of the Ministry that have continued under their watch.

2023, June – First Nations Leadership Council calls for the resignation of the Minister of Child and Family Development, Mitzie Dean, over the 2021 death of a child in foster care in Lake Errock, after the trial and sentencing of the perpetrators. The children’s case was handled by a delegated aboriginal agency, which had not checked in for seven months when the child died.

2021, June – report by BC’s Children and Youth Advocate, “Skye’s Legacy: A Focus on Belonging,” explored the life of a youth named Skye, who died of an overdose on her 17th birthday in August 2017. The report found that B.C.’s child welfare system left Skye without a sense of belonging, particularly as an Indigenous person, which contributed to her death. She was taken from her mother at age five and lived in fifteen different homes before her death twelve years later.

2021, May – the unmarked graves of 215 children on the Kamloops Indian Residential School grounds are confirmed. This leads to examination of other Indian Residential School sites, and further confirmation of similar mass unmarked graves at every school inspected so far.

2020, September – Traevon Chalifoux-Desjarlais was found dead in a bedroom closet, four days after he was first reported missing by a group home staffer.

2020 – present: most First Nations have accepted the demise of the Aboriginal Peoples Family Accord, the Tsawwassen Accord, and the Indigenous Child at the Center Action Plan. Instead, they have implemented the recommendations of the 2015 Report of MCFD Special Advisor Grand Chief Ed John. The report called for a Social Worker on every Indian Reserve, and the January 2020 enabling legislation provided delegated agency, to fulfill the Ministry mandate, to each First Nation.

2020, January – Bill C-92, “The Act respecting First Nations, Inuit and Metis children, youth and families” applies to Indigenous groups, communities or peoples, regardless of status or residence within Canada, who bear existing and inherent Aboriginal rights as per section 35 of the Canadian Constitution.

It is designed to affirm the rights and jurisdiction of Indigenous Peoples in relation to child and family services, and to set out principles applicable, on a national level, to the provision of child and family services in relation to Indigenous children. The Act creates a set of National Standards that must apply when working with Indigenous children, youth and families, and provides for changes to jurisdiction when making decisions about Indigenous lives.

The Act contributes to the implementation of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and provides an opportunity for Indigenous peoples to choose their own solutions for their children and families. Our children, our way.

2017, August – an Indigenous youth named Skye died of an overdose on her 17th birthday. She was taken from her mother at age five and lived in fifteen different homes before her death twelve years later.

2017 – A recent funding agreement between MCFD and the delegated aboriginal agencies brought caseload funding on par with levels within the MCFD.

2016 – APFA runs out of funding, dissolves.

2016 – 2014? – termination of regional delegated agencies – consultation and development program – follows from lack of support from individual communities for the regional, not community-based, process. Instead, most Bands sign on to deliver MCFD mandate themselves, following Ed John’s report recommending a social worker / agent on every reserve.

2016, November – Indigenous Resilience, Connectedness and Reunification–From Root Causes To Root Solutions; A Report on Indigenous Child Welfare in British Columbia Final Report of Special Advisor Grand Chief Ed John. The report calls for a Social Worker on every Indian Reserve.

2016, March – The B.C. Teachers’ Federation calls for Stephanie Cadieux, Minister of Children and Family Development, to resign after Patricia “Indigo” Evoy was found dead in a Burnaby, B.C., apartment March 10. She is the third aboriginal youth, in as many years, to die while receiving help from the B.C. Ministry of Children and Family Development.

2016, March – Patricia “Indigo” Evoy died while in Ministry “care.”

2015, December – Plecas Report part 1 released

2015, December

2015, December 22 – Sto:lo Tribal Council call for Bob Plecas and Ed John’s resignations, and reports to be shelved. They cite the misleading appearance of Indigenous representation with Ed John’s participation, which was not endorsed by Indigenous groups

2015, September – Grand Chief Edward John appointed Special Advisor on Indigenous Children in Care, “to engage First Nations and Aboriginal leaders in discussions to help the Province reduce the number of Aboriginal children in care; and, to engage with the federal government in meaningful work to enhance prevention and intervention work as well as address ‘root causes,’ as discussed in the report.” 6 month term

2015, September – NDP John Horgan calls for Minister of Children and Families Stephanie Cadieux to resign, following the death “in care” of Alex Gervais.

2015, September – Alex Gervais, age 17, died by falling out of an Abbotsford hotel room window where he had been “temporarily” housed by the Aboriginal delegated authority the Xylohmelh Society for 49 days.

2015, July – “Aboriginal Children in Care” report to Canadian Premiers identified “core housing need” among 40% of single parent families living on-reserve, among other major iniquities: in 2012, 40% of Indigenous children live in poverty; 43% of women in federal prisons are Aboriginal.

2014, December – The Lil’wat petition is admitted to the InterAmerican Court of Human Rights, which waived the requirement to prove exhaustion of the domestic remedy

2014, August – Canada’s Premiers directed provinces and territories to work together on solutions to reduce the number of Aboriginal children in child welfare systems. A report was provided to Premiers at the Council of the Federation (COF)

2013, November – report: When Talk Trumped Service: A Decade of Lost Opportunity for Aboriginal Children and Youth in B.C.

Mary Ellen Turpel-Lafonde, Representative for Children and Youth, BC

The report offered critical observations on how both Aboriginal organizations and BC’s Ministry of Children and Family Development (MCFD) have failed to meet the needs of children through what she has stated is a system of “fractured accountability”.

2011 – Child and Family Wellness Accord

Between leadership of the nine south island First Nations and urban Aboriginal community, known as the South Island Wellness Society, and the Province of B.C.

– to design and develop an Indigenous child services system for the care and protection of Aboriginal children, youth and families in the region.

-to restore, revitalize and strengthen the services in an effort to address the gaps and socio-economic barriers impacting the well-being of Aboriginal children and families

2011 – The Lil’wat petition to the InterAmerican Commission on Human Rights is accepted, the Edmonds petition, concerning the lack of Canadian jurisdiction to interfere in Lil’wat families living in Lil’wat territory

2010 – termination of APFA, end of funding for Child at the Center and Interim Child and Wellness Council

2008, July – Interim Child and Wellness Council established to gather further input for the Indigenous Child at the Centre Action Plan to ensure it reflects the knowledge of front line workers, youth, the community and leadership. The Council will then develop a workplan to advance and implement the Child at the Centre Action Plan.

2008, July – First Nations Leadership Council announces the Indigenous Child at the Centre Action Plan

2008, June – Prime Minister Stephen Harper apologizes for Indian Residential Schools

2008, April – VACFSS receives mandate from MCFD for “child protection,” meaning license to remove children from their homes and place them “in care”

2008, February – Overview of the Child Critical Injury and Death Investigation and Review Process in British Columbia

Prepared by The Children’s Forum: – BC Coroners Service – Ministry of Children and Family Development – Ombudsman – Public Guardian and Trustee – Provincial Health Officer – Representative for Children and Youth

2008, January 25 – the ‘Walking Together to Keep Indigenous Children at the Centre’ Declaration of Commitment among Indigenous Peoples “in” British Columbia

2008 Aboriginal Peoples Family Accord

A process of constituting regional delegated aboriginal agencies

2007, November 29 – the ‘All Our Relations’ Declaration of the Sovereign Indigenous Nations of British Columbia

2007 – GOOD PRACTICE ACTION PLAN

Ministry of Child and Family Development, BC

“Aboriginal peoples exercising their rights to jurisdiction over their children’s well-being, through self-determination, have strong and healthy children, youth and families.”

2006 – the Assembly of First Nations settles a number of individual and class-action suits against the Canadian government for harms caused by Indian Residential Schools.

2006 – the creation of an independent advocacy and oversight body – the Representative for Children and Youth by Hughes Review

2006, April – Hughes Review released

2005 – Hughes Review commissioned

To review :

the system for reviewing child deaths, including how these reviews are addressed within the Ministry,

advocacy for children and youth;

and the monitoring of government’s performance in protecting and providing services for children and youth

2005 – Opposition BC party NDP call for review into the two Aboriginal child deaths; advocates for other youth call for supports to youth in care

2002, September – toddler Sherry Charlie died in a foster home she was placed in by MCFD / delegated USMA (Nuu-chah-nulth) child services

2002, September – 23-month-old Chassidy Whitford was killed by her father on the Lakahahmen reserve near Mission in 2002, in Xyolhemelh / Fraser Valley Aboriginal Child and Family Services care.

2002, June – Formation of the First Nations Leadership Council, under the Tsawwassen Accord between the province of BC, BC region Assembly of First Nations, First Nations Summit, and the Union of BC Indian Chiefs.

2000-2001 – Ed John, an Indigenous Chief of the Carrier Sekani Tribal Council, is made the Minister for Children and Family Services, BC

2001, December 14 – VACFSS and the province sign the Delegation Enabling Agreement (DEA). VACFSS can provide a full range of delegated Resource and Guardianship services. It also provides non-delegated services through Indigenous Family Preservation and Reunification Services.

2000 – First Nations child and family services, national policy review – report by DIA and AFN

2000 – the Nisga’a Final Agreement includes agency over Children and Families, and the Nisga’a Child and Family Services is an extension of the provincial Child and Family Services law.

1999 – VACFSS began negotiations with the Ministry to deliver delegated services under the BC Act. The VACFSS Guardianship Pilot Project began.

1998 – A Review of the Implementation of the Report of the Gove Inquiry into Child Protection

1996 – creation of the Children’s Commission to review child deaths and oversee the activities of the new ministry

1996 – a series of community consultations leads to VACFSS receiving Indigenous support to get “designation status” – providing advocacy to families and notifying First Nations when their children were removed from their member families in the Lower Mainland

1994 – Gove Commission announced following murder of Matthew Vaudreille

1994, May – creation of Child, Family and Community Service Act, and the Child, Youth and Family Advocacy Act

1992 – “Liberating our Children, Liberating our Nation” – legislation review report calls for Indigenous jurisdiction over Indigenous children

(Community Panel Child Protection Legislation Review, British Columbia Report of the Aboriginal Committee: Eva Jacobs, Kwakiutle Nation and Lavina White, Haida; Fred Storey, Project Manager; Loretta Adams, Researcher; Faye Poirier, Administrative Support)

1989 -The Nuu-chah-nulth Department of Family and Child Services (Usma) becomes the first Aboriginal agency in Canada to exercise full delegated authority for child welfare.

1988 – the off-reserve advocacy union, United Native Nations, work in family reunification, and volunteerism spreading to child care and protection, is formalized as the Mamele Benevolent Society to facilitate in-home support programs, advocacy for families with children seized by the BC Ministry. This organization becomes the Vancouver Aboriginal Child and Family Services Society in 1992.

1986 – Child Welfare Committee

1980 – Child, Family and Community Service Act BC

1980 – Spallumsheen bylaw; child protection is carried out by the Band

1980 – Indian Child Caravan took place over Thanksgiving weekend, October 9-13, 1980. The Caravan began in Prince George and picked up more people along its route. The group advanced to Williams Lake and Mount Currie, and merged with people from the Interior and Vancouver Island communities before culminating with a rally in Vancouver. And sit-in outside the Minister’s house

1972-73 On March 9, 1973, the National Indian Brotherhood appeared at the Standing Committee of the House of Commons on Indian Affairs. Joe Clark, then a Member of Parliament from Alberta, moved that the Committee recommend to the House of Commons that the NIB’s

1972 Aboriginal Rights Position Paper be adopted as a description of aboriginal rights. It includes control of children and families.

1969 – Moccasin walk of a hundred miles, Indian Homemakers Association of BC,

raise funds for the British Columbia – wide Indigenous leadership gathering, which becomes the Union of BC Indian Chiefs, with a mandate to pursue the Indian Land Question.

1960s – “60’s scoop” indiscriminate and mass seizure of Indigenous children to state “care” and adoptions outside Canada. Follows delegation of social services from federal to provincial, and decriminalization of keeping children out of Indian Residential Schools

1920 – Indian Act amended to require Indigenous child attendance at Indian Residential Schools, on pain of imprisonment of the parents for non-compliance

BC’s first Superintendent of Neglected Children, 1919

1910 – Prime Minister John MacDonald: “It is readily acknowledged that Indian children lose their natural resistance to illness by habitating so closely in these schools [Indian Residential Schools], and that they die at a much higher rate than in their villages. But this alone does not justify a change in the policy of this Department, which is being geared towards the final solution of our Indian Problem.”

- end list *

Please find archival material at: ihraamorg.wordpress.com and check the archive in “Children” on this site.