Tags

aboriginal rights, Deb Mearns, Indigenous Peoples, Louis Cameron, Native Peoples Caravan, Parliament Hill 1974, Vern Harper

“The RCMP had the guns, the bayonets and the tear gas; we had a drum and a sheet of paper with our demands.” – Louis Cameron, Ojibway Warriors Society.

On September 29, 1974, the Native Peoples Caravan arrived in Ottawa. From uprisings that summer at the Two Springs occupation in Secwepemc and the reoccupation of Anishinaabe Park by the Ojibway Warriors Society, the Caravan was joined by people from coast to coast.

The next day, Monday September 30, they marched to Parliament Hill.

“The myth of a non-violent Canadian society was smashed to pieces in front of Canada’s Peace Tower on Parliament Hill on September 30th.”

Gary George’s 1974 article in “The Forgotten People,” reported the event, continuing:

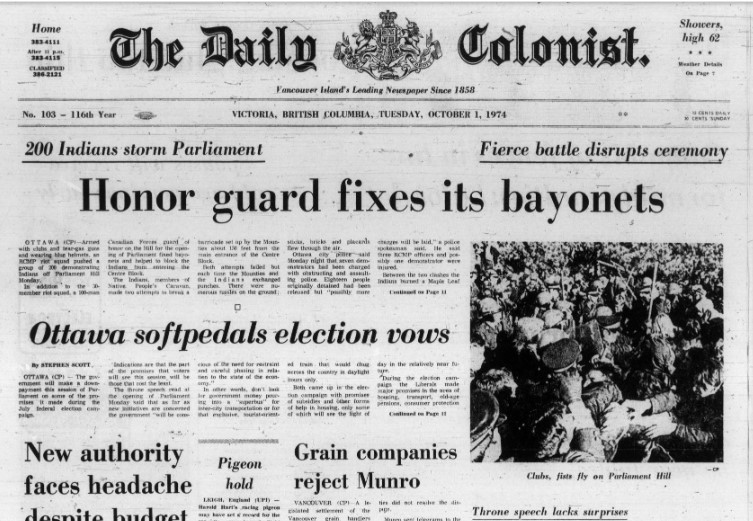

“The clash was between club-swinging, helmet-wearing, riot-trained RCMP and placard-carrying Native men, women, children and non-native supporters, all calling for positive action to end the oppression of Native people in Canada. This incident marked the 30th opening of the Canadian Parliament, the official beginning of the Trudeau government’s rule with a majority of seats in the House of Commons.

“The violence started when government officials refused to recognize the presence of the demonstrators. The pomp and ceremony of Parliament’s opening continued with few changes in tradition. When the estimated 200 demonstrators reached the stairs on Parliament Hill leading to the Centre Bloc they were stopped by RCMP and wooden barricades.

“As more people marched up the stairs, the front line of Native people was forced against the barricades. This clash lasted for about twenty minutes before both sides stopped physical conflict. When it finally quieted down the police moved back about a foot and stood four men deep, arms locked, facing the demonstrators. Directly behind them were the press and white spectators. The Native drummers started beating out the American Indian Movement’s rally song. Men, women and children joined voices in the song, filling the air with the chant. …”

Deb Mearns, part of the reoccupation at Two Springs and one of the coordinators for the Caravan, recalled the many events leading up to the Caravan:

“When we were surrounded by the RCMP up in Cache Creek and we negotiated an end to the roadblock and we didn’t get charged, I remember being told by a reporter that managed to sneak into the roadblock that he saw and heard the townspeople in Cache Creek were going up to the police roadblock on Highway 12 and telling the police, “just go in and shoot them.”

“It was not just the housing crisis. There were a number of issues involved. Louis Cameron came out after they had shut down their occupation, in Kenora, and we had already shut down the roadblock at Cache Creek, and we met in Vancouver at the Indian Center.

“They were talking about doing a caravan so we started working on that very quickly. I was one of the front runners, going ahead and organizing where we would go and where we would stay. We were flying by the seat of our pants, I tell you. I don’t know how we made it.

“When we got to Kenora, we used the last of our money to fly me to Ottawa, to make arrangements for us, and a Mohawk person met me there, picked me up at the airport. He told me the police were all inside the Indian Affairs office, expecting that’s where we were going to go. But he knew a place, and we went straight there – the old Union Carbide building that was owned by the federal government. It was abandoned. And it was perfect, you could see Parliament Hill from there.”

Vern Harper, one of its members and co-founders, gave a first-person account of the Native People’s Caravan in his 1979 book, “Following the Red Path ~ The Native Peoples Caravan 1974.” It begins with a quote to capture that day on Parliament Hill:

“The RCMP had the guns, the bayonets and the tear gas; we had a drum and a sheet of paper with our demands.” – Louis Cameron, Ojibway Warriors Society.

“The Caravan had set out from Vancouver only two weeks before, with little advance planning and no official funding. It had come to talk about housing, education and health care, but when the people of the Caravan arrived on Parliament Hill the Prime Minister refused to meet them.”

– Harper, Following the Red Path.

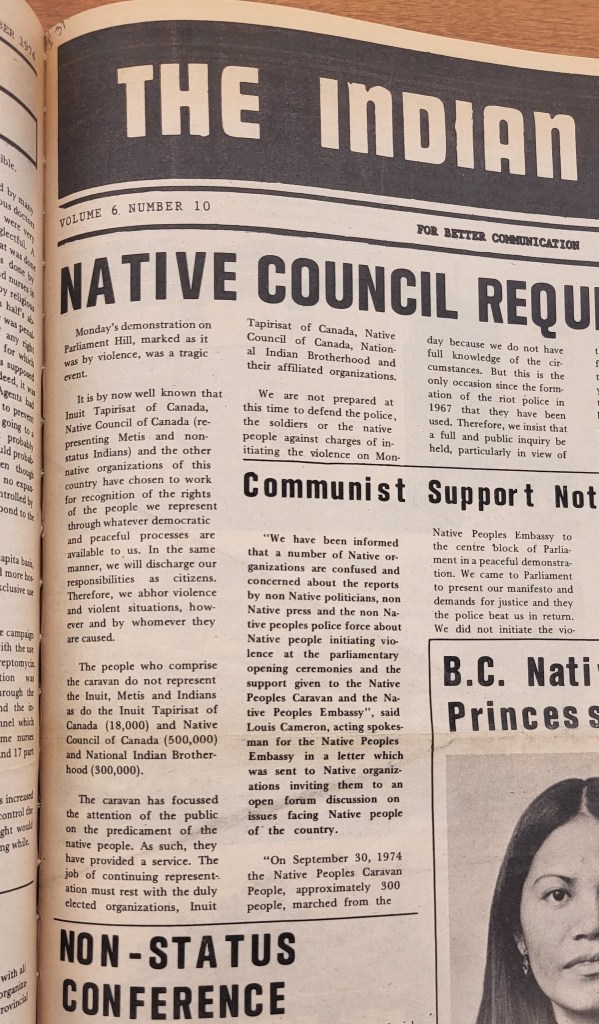

The Native Peoples Caravan had clearly distinguished itself from government-funded, centralized Indigenous organizations. In the UBCIC’s newspaper, The Indian Voice, the editors acknowledged and thanked the Caravanistas, but distanced their Union, the Native Council of Canada, the Inuit Tapirisat and others from the grassroots caravan at the same time. See the newspaper clipping from The Indian Voice, below.

Vern Harper described the difference this way:

“We knew that official Native organizations like the National Indian Brotherhood and the Native Council of Canada weren’t being listened to. It was quite clear to us that these national Native organizations, which had been created by the government in the first place, were just being used. On the one hand, the government would say, “We’ll only talk to your leaders,” but when the leaders tried to talk to them the government wouldn’t listen. And so we decided that we would organize to bring Native people themselves to Parliament.

“We knew that they were ineffective, and that they were not really helping to change things for Native people. In fact, their main role seemed to be to keep the lid on Native protest and Native demands. The government had … funded these organizations in the first place, and it was able to use them to protect itself from any kind of confrontation or direct criticism. When Native people tried to go around the organizations, the government’s line was always, “We can only talk to your official representatives.” Even this was false, because the government wasn’t talking to the official Native leaders. But in 1974, the reality of Native organizations was well established. Many of the people on the Caravan had been in government-funded organizations and gone through that whole frustrating experience.”

The Manifesto, that piece of paper Louis Cameron mentioned, was four pages long.

“The hereditary and treaty rights of all Native Peoples in Canada, including Indian Metis, Non-status and Inuit, must be recognized and respected in the constitution of Canada. It is the continuing violation of our hereditary rights that has resulted in the destruction of the self-reliance of the Native peoples. We are …the most impoverished peoples of Canada.

… the Department of Indian Affairs operates to serve business and government interests – not the interests of the Indian people. We demand a complete investigation of the Department of Indian Affairs by Native People and the transfer of its power and resources to Native communities. …”

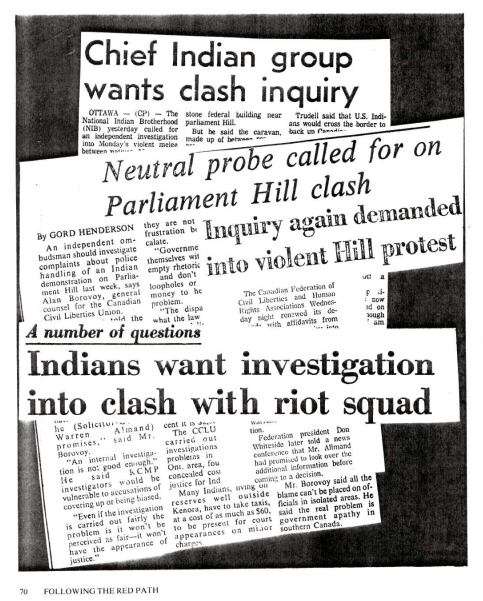

Deb Mearns explained the effect of the September 30 event in news media:

“It was a huge eye-opener for the Canadian public because we were an invisible people, and all of a sudden they were faced with us, the Anishinaabe, the Caravan to Ottawa – and how we were treated when we went to Parliament Hill to demonstrate, it was all over the media in Canada and the United States. It was a real awakening – they didn’t know anything about us. There was racism, and there was also a real shock for people to find out that we exist, and the conditions in which people lived.”

*

The Summer 2024 issue of Archive Quarterly features the reoccupation of Two Springs, Secwepemc, and the armed highway toll there, and how it led into the Native Peoples Caravan.

*

The following images from Vern Harper’s 1979 book, “Following the Red Path ~ The Native Peoples Caravan 1974.”

The following images from newspapers at the time:

The Manifesto of the Native Peoples Caravan: