Tags

aboriginal title, Comprehensive Claims Policy, extinguishment policy, Reconciliation, TRC, Truth and Reconciliation

Part 3 of this week’s blog, No More “Reconciliation Sticks”

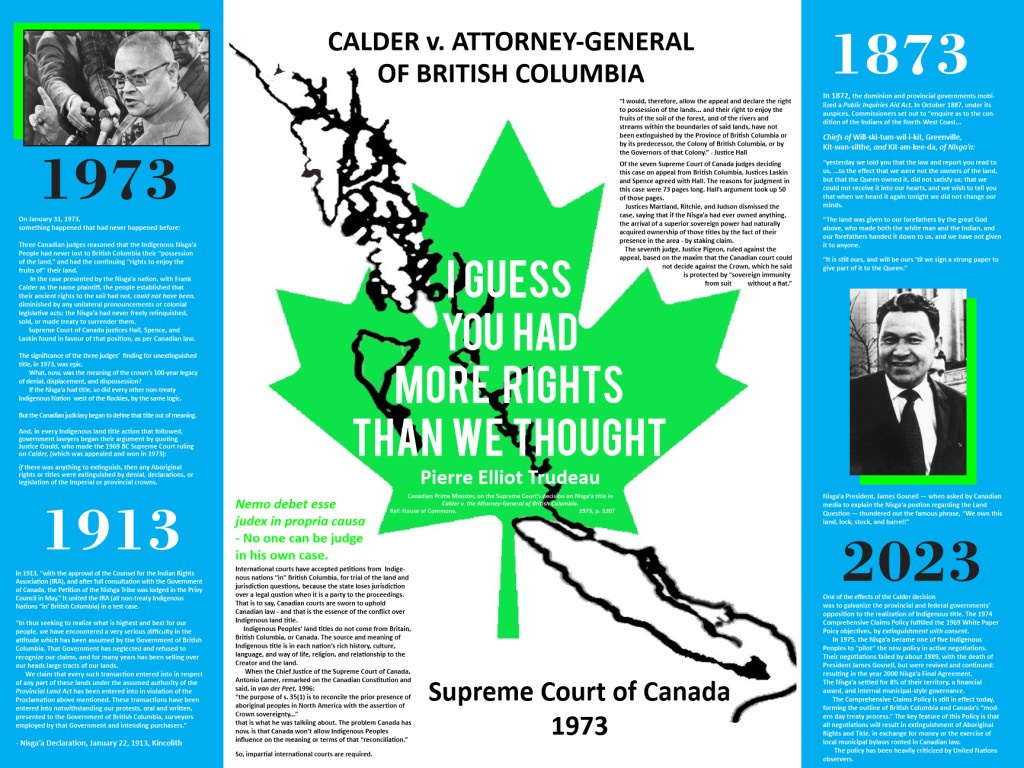

The term “reconciliation” has morphed from the 1996 Van der Peet ruling into government “Statements on reconciliation,” into the 2009 formation of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), into the judicial results of aboriginal title cases.

What has not morphed is the Canadian government’s policies.

Does the PR campaign match the policy?

“The concept of reconciliation,” as the federal government more cleverly put it in their secret policy, four years before the TRC would be mandated by the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement, might butter more toast than the reality of the government’s Comprehensive Claims Policy (CCP).

The secret policy writers noted that the concept of reconciliation would secure investment, because it sounds good, without adding any liabilities by talking about it, because they don’t mean anything good by it: just making Aboriginal societies conform and resign to colonial control.

Government policy on “land claims,” the bottle neck corridor through which any and all state recognition of Indigenous land ownership is achieved, is book-ended by discretionary suspension of Indian Act relief funds in the case of non-compliance, or roadblocking, or refusal of an Indian Band (First Nation) to negotiate its way into becoming a provincial municipality and releasing the government from liability for past harm.

“Reconciliation” has not shifted this policy.

Reconciliation in the decisions of aboriginal title cases

In 2017, the 20th anniversary of the Supreme Court of Canada’s Delgamuukw decision (1997) was marked by heavy equipment building pipeline access roads over the unsurrendered, unceded properties of Wet’suwet’en Chiefs whose title to the land was fully evidenced at trial. Any Canadian can read the transcripts and see the maps.

Briefly, the head chiefs Delgamuukw (Gitxsan) and Gisdayway (Wet’suwet’en) were suing for a declaration of title and jurisdiction on behalf of their nations, with small exception. The Supreme Court of BC and CJ Allen MacEachern dispatched the Gitxsan and Wet’suwet’en claim in 1991 with some of the most racist language ever heard in a court room.

In Delgamuukw v. British Columbia at trial in BC in 1990 and 91, British Columbia had counterclaimed for a declaration that the appellants have no right or interest in and to the territory or alternatively, that the appellants’ cause of action ought to be for compensation from the Government of Canada. MacEachern agreed with them, on the whole. The province’s lawyers were, after all, from his old law firm of Russell and DuMoulin. MacEachern pointed out the impossibility of wandering “vagrants” such as the plaintiffs to have title to land. And if they ever did, he reasoned, it was displaced by the presence of the crown.

At the Supreme Court of Canada, Chief Justice Antonio Lamer didn’t declare any title either. He found a lot of errors in MacEachern’s reasons and in the province’s arguments, ultimately confirming the clear appearance of Gitxsan and Wet’suwet’en title; ordered a retrial; and took the chance to tell them:

“Ultimately, it is through negotiated settlements, with good faith and give and take on all sides, reinforced by the judgments of this Court, that we will achieve what I stated in Van der Peet, supra, at para. 31, to be a basic purpose of s. 35(1) — “the reconciliation of the pre-existence of aboriginal societies with the sovereignty of the Crown”. Let us face it, we are all here to stay.”

It’s effectively the same as the Truth and Reconciliation Commission reporting that Indigenous Peoples “must” come to “mutual respect and recognition” with the colonizer. Presumably, complete forgiveness on the part of the Indigenous goes along with that.

Neither “reconciliation” nor court rulings have altered the bottom line in Canadian policy and practice.

Antonio Lamer’s successor as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Canada is CJ Beverly McLachlin. She has picked up the torch of reconciliation with total enthusiasm, letting the truth of reconciliation’s subversive powers burn brightly.

In Tsilhqot’in Nation, 2014, she reasoned:

“The Court in Delgamuukw confirmed that infringements of Aboriginal title can be justified under s. 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982 pursuant to the Sparrow test and described this as a “necessary part of the reconciliation of [A]boriginal societies with the broader political community of which they are part” (at para. 161), quoting R. v. Gladstone, [1996] 2 S.C.R. 723, at para. 73.” [16]

Just to rephrase: infringement of Aboriginal title is a necessary part of reconciliation. Incidentally, so is impairment of Aboriginal title and rights; and, apparently, the extinguishment of Aboriginal title and rights by negotiation under the Comprehensive Claims Policy.

She further clarified:

“As Delgamuukw explains, the process of reconciling Aboriginal interests with the broader interests of society as a whole is the raison d’être of the principle of justification.” [82]

(Note: The Supreme Court of Canada devised the “justification test” in 1990, when it ruled on the Sparrow fishing case. The category keeps growing, but Aboriginal rights and titles can justifiably be infringed that Canada and the provinces want rally badly: logging, mining, the settlement of foreign populations to do those things; development; ski resorts; hydro-electric facilities; roads; etc.)

The result of Tsilhqot’in Nation was a declaration of Aboriginal title to part of the Tsilhqot’in traditional territory. It is the first and only land with such a designation, arriving 40 years since the first admission of Aboriginal title in the Canadian common law, in 1973 with Calder.

Ten years later, jurisdiction on the ground remains rather fully snarled in bureaucratic reluctance. Justifiable infringements carry on like business as usual.

This is the policy that “reconciliation” is all about.

Subterfuge is consistent with the historical record

Even in a brief survey of examples which come to mind right away, the legacy of deceit – from bad faith to fraud – make it hard to believe the idea that Canadians are going to do the right thing this time. It makes no sense to ignore the past. Indigenous Peoples aren’t going to.

To make a clean sweep that encompasses the beginning and the present, we should start with the fact that the British crown honoured none of its promises. It has never held Canada accountable to the Executive Orders it delivered by the monarchs and the Privy Councils, and, from the Canadian side, the Governors and Attorneys General have only ever stonewalled Indigenous attempts to access “British justice.”

It’s a pattern repeated around the globe, where British forces route whole villages, coastlines and interiors; supplant Chieftains with Magistrates propped up by force and coercion; populate the place with re-purposed chattel shipped out from Scotland, Ireland, prisons or orphanages; funnel resources out of the newly colonized and re-populated country; and later some Governor or judge scratches his head, for the record, and notes that the law as it was written appears to have been mislaid.

Canada is no exception.

In 2007 the First Nations Unity Protocol Agreement saw the alignment of every Band involved in the BC treaty process (except one) stage massive protests: the government’s negotiating mandate was not consistent with the basis of the BC Treaty Commission, the 19 Recommendations made by the BC Task Force that formed it in 1991. Furthermore, the Delgamuukw decision, SCC 1997, elevated judicial recognition of Aboriginal title well beyond British Columbia’s working definitions, but this did not change the negotiating mandate.

The negotiating mandate follows the Comprehensive Claims Policy, 1974, updated in 1978. The province knew that was its mandate when it entered negotiations, loaning hundreds of millions to First Nations and putting them within the purview of third-party remedial management, based on their Indian Act financial responsibilities.

Now, in these times of Reconciliation, that negotiating mandate has not changed. The only possible result of a land claims negotiation between First Nations and the state is that the unsurrendered Indigenous land in question will be relinquished for a financial settlement, sometimes including fee-simple packages of land which are now the property of the province. This is extinguishment of Aboriginal title.

For three decades, UN Committees for implementation of international treaties on Racial Discrimination, Civil and Political Rights, Social and Economic Rights, and more, have made long lists of unresolved violations. Extinguishment, recently re-named as “certainty,” is one of those violations. They have little to show in response to their recommendations to Canada.

The Inter American Court of Human Rights has admitted two national Indigenous-led cases against British Columbia and Canada that there is no “domestic remedy” to the Indigenous dispute with Canada. Among many other reasons, that’s because Canadian courts aren’t an impartial tribunal. One case was brought by the Hulquminem Treaty Group when it reached the above mentioned impasses in the BC treaty process. The international court’s findings have also not affected the government’s negotiating mandate.

The Tsawwassen Final Agreement was ratified later that year, about 1% of the claimed land area, a cash settlement, and offering a $15,000 payment for every yes vote. The Minister of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada, Chuck Strahl, said “who am I to say it’s a bad deal?”

After the 2007 BC Supreme Court decision in R. v. William, the Tsilhqotin Nation case, communities across British Columbia lit up June 21 with roadblocks, information check-points on major highways, and various demonstrations. It really was meant to be the longest day of the year for Canadians.

As of 2010, Canada announced “Aboriginal Day” on June 19th. Grants and organizations piled up in displays of culture and dancing in parks, and the year that Vancouver hosted the Winter Games was cleared of protest ahead of advance delegations of international journalists preparing to cover the Olympics. Coincidence?

Can everyone remember as far back as 2012 and Prime Minister Harper’s Bill C-45? It gutted funding to Aboriginal organizations. Tribal Councils and Friendship Centers lost 75% of their income overnight. That was four years after he apologized for the Canadian government’s role in Indian residential Schools.

(Note: the funding cuts weren’t related to any corresponding reduction in diamond mining, fracking, logging, fishing, industrial agriculture, or other reduction in exploitation of unceded lands.)

But the intention of the Indian Residential Schools was exactly the same as the intention of the Bill C-45 budget cuts, and the omnibus bill’s corresponding legislative architecture to municipalize First Nations. (Check back for Part 5: Reconciliation as Municipalization)

Canada’s prima facie goal is assimilation of the Indigenous nations and polities into “the body politic of Canada. Then there will be no Indian Department and no Indian question.” The Superintendent of the Interior, as he was then, Duncan Campbell Scott, was clear and unapologetic about the goal in 1920.

The only discernible difference today is the performance of apologetic behaviour by leading Canadian politicians like Prime Minister Justin Trudeau. But the same goal is clearly defined by the only possible result of the only negotiations, and the only political or judicial recognition, that Canada will engage or afford Indigenous Nations: assimilation into the body politic of Canada.

Which brings us to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

Whose truth? And whose reconciliation?

The TRC wasn’t really looking for the Canadian government’s truth. It interviewed survivors of Indian Residential Schools; it held events for the former students and their families; it catalogued testimonials. It did not collect stories from the surviving perpetrators of the crimes, and the architects and financiers of the institutions. It did not search archived government memos concerning the receipt of visiting doctors’ reports that children were starving, being abused, and dying.

Wouldn’t it be helpful to know – and collect statements – whether the government of Canada knew that the schools were turning into graveyards? If the government officials in charge of those schools deliberately recruited disgraced “teachers” from the notorious Irish industrial schools run by the Christian Brothers? If there is a record of that political decision to ignore what was happening, because it was furthering the stated objective of “killing the Indian in the child”?

Keep in mind that was the mandate of the “schools.”

At some point the question has to be answered: is it really possible for the perpetrator of the crime to sit in judgment of it and prescribe the actions of atonement?

If the TRC’s report and recommendations can possibly be taken seriously, they would have to be matched equally by a Commission of the Indigenous Nations’ own making. They would have to be qualified and heavily amended to include the recommendations of the Indigenous Peoples. And Indigenous parties would have to have the power to ensure those recommendations would be met.

Alternatively, why not have an Indigenous-mandated Commission, and that party to the dispute can run the reconciliation program? Does that sound absurd? More absurd than having a Commission that’s mandated and run by Canada – one of the named perpetrators of the crimes under investigation?

But the TRC did not contemplate any crime other than what happened at Indian Residential Schools. And yet, the “reconciliation” that fills the media and the municipal, provincial, and federal government statements are made to refer to all matters of imbalance and grievance between Indigenous Peoples and the state.

Many former students and their family members attended the ceremonial report of the TRC. Many were raptly attentive to the Pope’s apology. And many of them were not able to accept the conditional, highly qualified TRC report; many found they were not able to accept the Pope’s brief apology and extended remarks on the Christian faith.

Why is that? That’s because Canada still has all the land and all the money from the resources and all the power to enforce all the decisions they make about how to exploit the land. The churches haven’t given back any land that was gifted to them, either by hopeful indigenous leaders or by the government, and the churches are not going to bat for indigenous Peoples on the broader issues.

It’s because Canada still has control of the governance structures that Indigenous nations are forced to crouch under; it has control of the fate of the little children and their families who struggle “on a weekly, daily, and hourly basis”[i] to make ends meet. It has everything – except the consent of the Indigenous Peoples.

It is a very ungainly suggestion that the TRC makes when it reports that Indigenous Peoples “must” engage “mutual respect and recognition” in order for reconciliation to work.

The TRC itself was expressly forbidden, by mandate, to engage in “fault finding” as it heard evidence of gross, mass crimes. The mandate forbade Commissioners to subpoena witnesses, to form criminal charges, and even to record the names of perpetrators proven out in testimonies.

Come a little further away from the mass media noise, and consider. Investigation of the school graveyards was Call to Action numbers 75 and 76. A Commission with no mandate to “find fault” has made itself the authority on proceedings to uncover the victims of first and second degree murder.

Is it likely that “reconciliation” proceed while “justice” is denied?

The biggest hoax since the Trojan Horse

But we have to stop talking about reconciliation as if it means anything other than what the judges said it does: making Indigenous Peoples conform to the Canadian way of doing things, at least to the point where there’s no competition or conflict for the Canadians.

This is also the “reconciliation” of the TRC, and the apologies. It’s procedural; it’s “getting over it;” it’s saying “sorry” to make the injured party say, “it’s okay,” and justifying business as usual, as if it has been consented to in the receipt of the apology.

The “reconciliation” of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s tear-stained camera opps – the imaginary world where Canadians are moved by understanding the harm they have caused, and actually change everything – is a Public Relations campaign. Not only in Canada but all over the world.

The policy is the policy, and it has nothing to do with contrition. Nothing to do with balancing the scales; nothing about Indigenous self-determination, jurisdiction, and title; nothing like reparations or cooperating with an independent tribunal. Nothing about exposing a Supreme Court that is prima facie guilty of judicial inactivity in the presence of genocide, and clearly abetting it.

The Public Relations “reconciliation” bears no resemblance to the policy. The policy constructs a funnel of release and indemnification of “the provinces, Canada, and anyone else” for any and all past harms. It requires that “this is the final settlement of Aboriginal claims.”

~

Thank you very much for reading. Today’s post has been interrupted by a computer crash, so it may be improved a little once that’s resolved!

Takem i nsnukw’nukw’a.

Check back for Part 4 – Enforcement of Reconciliation, tomorrow; and Part 5 – Reconciliation means Municipalization, Friday.

[i] The Reconciliation Manifesto, Arthur Manuel, 2017.