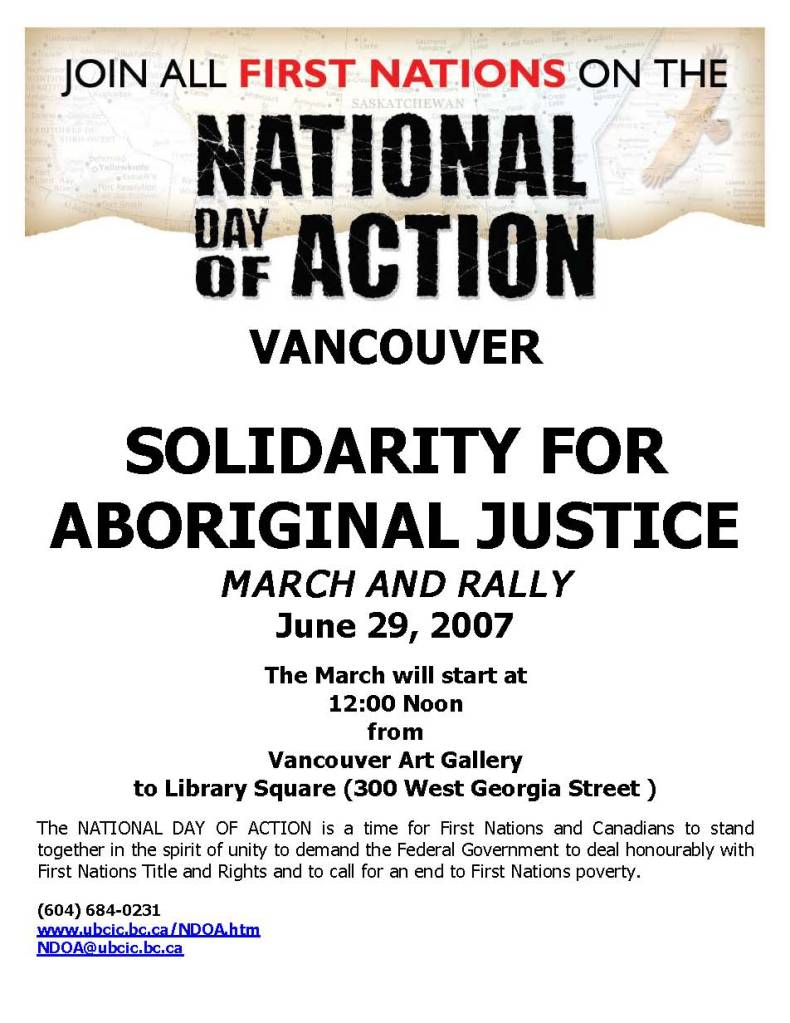

The Assembly of First Nations called for a National Day of Action in 2007. The call was answered in over 100 locations across Canada, where people stopped traffic, trains, and TV news on June 29th.

AFN Chief Phil Fontaine made the call for immediate action to address the situation of Indigenous Peoples in Canada.

At the end of the first National Day of Action, June 29, the AFN press release explained:

“The national chief called on the federal government to honour its promises to First Nations; to implement the plan agreed to at the first ministers meeting on aboriginal issues in Kelowna, BC; to apologize to survivors of residential schools; and to work with First Nations to give life to their rights as recognized in Canada’s constitution.”

Indigenous communities and organizations took the chance to promote the urgency of issues on the ground, while they could rely, for the day, on “law enforcement officials for their commitment to a measured and non-confrontational approach,” according to the AFN Chief’s press statement, June 2007.

A second National Day of Action was called for May 29, 2008. And a third – unannounced – continued in their tracks in June 2009.

“The message we gave was, our rights are being trampled on and Canada goes out to international governments and makes it look like everything’s alright, and it’s not. Canada is actually in denial. The government may put out a positive message, but if you go back to the First Nations, they’re not happy with any of it.” Chief Desmond Peter, pictured, at an information roadblock on Highway 12 through Tsk’wáy’laxw. May 29, 2008. (The St’át’imc Runner newspaper, July 2009)

On June 19, 2009, Canada’s Governor General broke in to what was becoming an annual thing: 24-hour roadblocks truly marking the solstice season with “the longest day of the year” for Canada.

GG Michaelle Jean declared, in a three-paragraph news release, that “National Aboriginal Day is celebrated on June 21, 2009.”

Remarking on the first anniversary of Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s formal apology to Indian Residential School students in 2008, Jean said:

“The time has come to move beyond the injustices of the past and build a future together that history will show brought us together in respect, dignity, equality and solidarity. This is how we will break down the solitudes that, for too long, have isolated us from one another. In the spirit of this new age, let us look to our youth, whose full participation in creating a new era of harmony is our best chance for success.”

Ever after, Canada looked to the youth and funded all manner of song and dance displays, made funds available for celebrations in every town and city, and called it reconciliation in action.

The National Day of Action was displaced from the calendar, as communities supported their young people to enjoy some pride in their identity and talents, and pick up a cheque for their otherwise little-noticed culture.

The issues which brought out the information roadblocks, signs, banners, speeches, and occupation of railways, were not reconciled.

In Vancouver, 2009, an “Aboriginal Solidarity Day” took place at Trout Lake on June 29th, and on June 24th the Olympic Resistance Network marched downtown; but by June of 2010 there was no continuation of the coast-to-coast-to-coast event.

The first National Day of Action got results. Federal damage-control went into effect within days of the first call to action in 2007.

“Indian Affairs Minister Jim Prentice has been conducting a cross-country campaign to deflect wide-spread direct action campaigns during the June 29 Day of Action. In particular, a long-outstanding specific claim has apparently been settled, expanding the Roseau River First Nation reserve territory on the eve of June 21, National Aboriginal Day (although important questions have already been raised about the future uses of the land parcel). Chief Terrance Nelson has publicly acknowledged this settlement. While he has emphasized that problems with Ottawa remain, he has called off his threat to block major rail lines. This use of recent specific-claims reforms as an immediate tool to neutralize protest this month reflects the wider tendency of the present government to drive policy change primarily in response to immediate political embarrassment.” So reported James Lawson, a teacher at UVic, in the Socialist Project’s “The Bullet.”

The 2007 Day of Action had raised the visibility of severe circumstances, endured under protest, for generations. They are circumstances that have been rationalized all along by Canada’s quest for development, and to “build this country.”

Land claims negotiations were going nowhere. In BC, $975million in funding to the BC treaty process over 15 years (most of it to federal and provincial teams), had settled nothing.

Canada’s Supreme Court continued in its unilateral and assimilationist strategy to turn “Aboriginal title” into “the right to be consulted,” confirming the “pleasure of the crown” over poorly defined rights in its 1997 Delgamuukw ruling and subsequent interpretations; and in its Haida and Taku, ruling, 2004; and in Tsilhqot’in Nation, 2007.

Prime Minister Paul Martin’s very brief attempt to release $5billion in Transformative Change Accord funding, to housing, education, land issues, and more, had just brought down his government. The Liberals were swept away by a vote of no-confidence in Parliament just days after the first chapter of that Accord was signed in BC, the Kelowna Accord, at the end of 2005. Martin tried to push a Private Member’s Bill through to disperse the assembled budget, but it failed and suddenly in its place – six months later – a $2billion Indian Residential Schools Survivors Settlement Agreement was presented.

One of the cringey details amplified in the call for action was the federal government’s ongoing 2% limit on annual funding increases to Aboriginal communities, clamped on in 1986 at a time when the housing deficit in Native communities was estimated to be worth $400million, and climbing. Reckoning by the federal subsidy of about $10,000 per new house build, at that time, those 40,000 houses still haven’t been built. The 2% cap didn’t move until 2016.

The National Day of Action was called to touch the brakes on Canada’s relentless extractive industries, shipping the natural wealth of Indigenous Nations off the continent by the super tanker, and leaving First Nations futures in the clear-cuts, toxic tailings dumps, encroaching settler suburbia, and hydro and pipeline rights-of-way.

The unmitigated Canadian legacies were then, and are now: denial of the registrable values of their land titles; running circles in policy whirlwinds around education and child welfare – that all puffed out before any traction was gained; virtual landlessness; and the shackles of an Indian Act which, to date, prevents all manner of economic development on-reserve.

In the further spirit of Canada’s “reconciliation of Aboriginal societies with the sovereignty of the crown,” (Van derPeet, 1996) First Nations have since been invited to import Canadian legislation over themselves by consent, thereby releasing their own laws along with the arbitrary Indian Act controls of all manner of socio-economic development. This is not seen as a suitable resolution by many.

Arguably, the National Day of Action never completed its work.

On May 29, 2008, Ontario’s Minister of Aboriginal Affairs said of the NDOA, “I’m confident this day will serve to strengthen relationships based on mutual respect and understanding.”

“Aboriginal Day” 2025, however, brings an escalating situation in Canada’s idea that it can fast-track industrial development over Indigenous rights.

On June 29, 2007, Minister of Indian Affairs (as it was then) Jim Prentice said, “The express purpose of this day was to raise awareness of the serious issues facing Aboriginal People in this country.” But since Canada has taken charge of telling Canadians what those issues are, controlling the narrative with its flood of publicly-subsidized propaganda in aid of “Aboriginal Day,” it is made to seem that those serious issues don’t foremost include land and jurisdiction; reparation and restoration; and self-determination at an international standard of recognition, not the starvation afforded by a Canada UNDRIPA that has nothing in it.

Another consideration in taking the date was described by BC Premier Gordon Campbell in June 2009:

“National Aboriginal Day, June 21, is an important opportunity for all Canadians… In just 236 days, the eyes of almost every continent will turn to British Columbia for the 2010 Olympic Winter Games. They will see our spectacular natural environment. … And they will no doubt see, and judge for themselves, our relationships with First Nations.”

“We have signed modern-day treaties with six First Nations… We can all take pride as a province for the steps we have taken together to build a New Relationship… So as we celebrate National Aboriginal Day, and move towards Canada Day, we should recognize the tremendous contributions First Nations have made to our province and our country.”

“I congratulate the federal government on continuing this process of reconciliation by declaring June National Aboriginal History Month. The celebration of National Aboriginal Day on June 21 will now be bolstered by a month of cultural awareness.”

Campbell’s brief self-congratulatory affirmation of the announcement of Aboriginal Day was answered immediately, by many, including Chief Kakila, Hereditary Chief Clarke Smith of Tenas Lake, Samáhquam, St’át’imc:

“Mr. Premier. Your words and statements are empty. Canada and BC Government purposely created laws against us Aboriginal people for over 100 years. … How can you even think that BC is trying to build a New Relationship? … All the Supreme Court Decisions such as the Delgamuukw mean nothing to you Greedy Leaders. Court Rulings you don’t follow. … Perhaps you need to really read the Delgamuukw Supreme Court Decision, it states that the “BC Government cannot extinguish Aboriginal Title and the Rights that flow from such Title.”

“All the evidence is in the Minutes of Decisions your governments made over the last century or so. How to rid of the Indians.”

The last-minute declaration by the Governor General in 2009 didn’t change the reality.

One Tribal newspaper carried three June events which dulled the media spin.

“Ancestors Block Trans-Canada Highway Expansion. Neskonlith, Secwepemc. The disturbance of human remains believed to be more than 2,800 years old has halted work on the Trans-Canada Highway near Chase.”

“Alberta oil held up on Highway 52. On June 20, the Kelly Lake Cree Nation, near Beaverlodge, about 500 kilometres from Edmonton, began stopping all oil and gas rigs from passing along Highway 52, a remote highway mainly used by crews traveling between Alberta and B.C.”

“Mohawks at Akwesasne stop border guards. Canadian border guards at the Akwesasne Reserve international crossing are involved in a militarization of the Canada-US border. However, the presence of Canadian police carrying guns on and around the Reserve is not welcome. It has been described by Akwesasne leaders as an open conflict. Mohawk sovereigntists blocked entry to the guards. Canada and USA are also demanding new ID for natives crossing the border, apparently in violation of the Jay Treaty.”

In 2007, the Assembly of First Nations stretched its considerable wingspan to shelter more than 100 community-based demonstrations. In 2009, the unmistakeable message of the Governor General was that only celebrations of reconciliation are safe on Canadian streets.

With the T-shirt for the day, on May 29, 2008, in Ottawa. Photo by Powless, on Flickr.