Tags

In 2017, the Committee for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination made 32 recommendations to Canada that pertain directly to Indigenous Peoples.

Canada’s last review by the UN Committee for the Elimination of all forms of Racial Discrimination concluded in 2017. The UNCERD provided concluding observations and recommendations, and Canada’s next report was due on November 15, 2021. This report has not been filed, and the corresponding meeting has not been scheduled.

32 of the CERD’s most recent recommendations relate directly to Indigenous Peoples: from land rights to discrimination and racism in the public education system. They are copied below; the recommendations have not been achieved.

Furthermore, the Committee drew Canada’s attention to recommendations it made in 1997, and has repeated at every review since then, concerning:

- the right to consultation and to free, prior and informed consent of Aboriginal peoples whenever their rights may be affected by projects carried out on their lands, as set forth in international standards and the State party’s legislation;

- to seek in good faith agreements with Aboriginal peoples with regard to their lands and resources

- find means and ways to establish titles over their lands, and respect their treaty rights;

- Take appropriate measures to guarantee that procedures before the Special Tribunal Claims are fair and equitable …

That was in 2012.

When the CERD referred to its 1997 recommendations again in 2017, it got even more specific, adding the following to the list:

- End the substitution of costly legal challenges as post facto recourse in place of obtaining meaningful free prior and informed consent of Indigenous Peoples.

- Incorporate the free, prior and informed consent principle in the Canadian regulatory system

- amend decision making processes around the review and approval of large-scale resource development projects like the Site C dam.

- Immediately suspend all permits and approvals for the construction of the Site C dam.

- Conduct a full review in collaboration with Indigenous Peoples of the violations of the right to free prior and informed consent, treaty obligations and international human rights law from the building of this dam and identify alternatives to irreversible destruction of Indigenous lands and subsistence which will be caused by this project.

- Publicly release the results of any government studies of the Mount Polley disaster and the criminal investigation into the disaster, before the statute of limitations for charges under these Acts expires.

- …take measures to mitigate the impact through … fair remedy and reparations.

As we all know, Site C is going ahead and BC media shut out Indigenous opposition. We also know the BC government took over a private prosecution of Mount Polley mine’s owners – and dropped the charges. West Coast Environmental Law wrote a great article about that.

As for “costly legal challenges,” they are the only way to identify Section 35 Aboriginal rights in Canada, on a case-by-case basis, unless you surrender your rights in toto and accept a deal with Canada instead.

No review of violations of free, prior, informed consent have gotten underway since 2017.

What will Canada tell the Committee this time?

That on top of a new record-breaking trial over Aboriginal title – the Cowichan 2025 decision is now the longest, at five years of trial – the positive decision in favour of the Tribes was appealed by settler governments before they could have possibly had time to finish reading it?

And then every purveyor of news media – state or commercial – hammered the incitements to hatred spoken by ignorant civilians, on repeat? To the point that the Cowichan Tribes had to issue a statement concerning the “Misleading and False Information Regarding Aboriginal Title Case,” (October 27) tantamount to a cease and desist order? (October 27)

UN treaty bodies make a difference

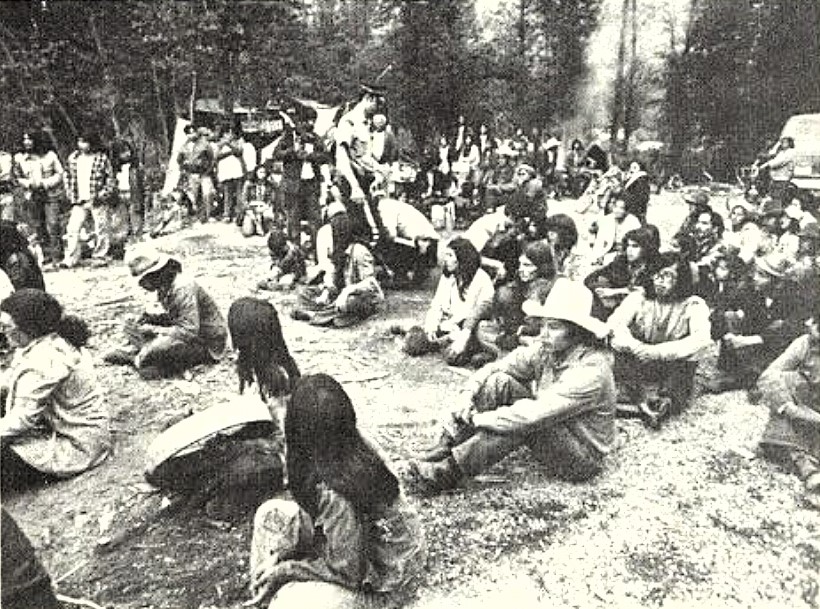

In the last reporting cycle to the CERD treaty body, 75% of the reports from Non-Governmental Organizations and civil society were sent by Indigenous organizations – fifteen of them.

UN treaty bodies make a difference, even though Canada does not take its Charter obligation seriously when it comes to educating the public about international human rights law generally, and UN mechanisms in particular.

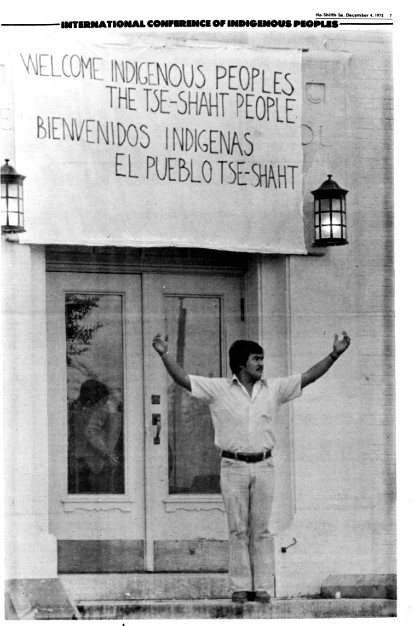

The CERD passed remark on the BC treaty process in 2007:

“While acknowledging the information that the “cede, release and surrender” approach to Aboriginal land titles has been abandoned by the State party in favour of “modification” and “non-assertion” approaches, the Committee remains concerned about the lack of perceptible difference in results of these new approaches in comparison to the previous approach.

“The BC Treaty Commission version of the Canada comprehensive claims extinguishment policy has all but collapsed since then. Only one Final Agreement was completed after Tsawwassen and Maa-nulth were heavily lubricated through ratification – within weeks of the CERD report – in 2007, and BC has had to reinvent (yet again) the Indigenous surrender policy that has been formally in place since 1914.”

They call them “reconciliation of rights” and “jurisdiction” agreements now.

Reinvention is at the center of all Canada’s reports to treaty bodies, when it comes to Indigenous Peoples.

Right before the August 2017 date for Canada’s appearance before the CERD, it sent four federal ministers to the Assembly of First Nations annual assembly, July 25-27, where they told everyone that Ottawa is going to rescind the Indian Act. Bennett (Minister of Indigenous Affairs), Wilson-Raybould (Minister of Justice), McKenna (Environment) and Goodale (Public Safety), all described a bright new future to come.

They did this moments before the in-person report to CERD in Geneva, allowing Canada to reply to all of the issues raised in the fifteen Indigenous reports by referencing the July meeting and the appearance of an announcement there.

However, the only substance to Ottawa’s mission to the AFN Chiefs in July – half of whom boycotted the all-expense-paid meeting in Regina – was that the Ministry of Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Development will no longer claw back unused capital funds after twelve months.

An excerpt from one of the independent reports to the last CERD review of Canada:

“Skeena watershed and coastal Indigenous communities depend on the salmon for food, their economies and cultures. This (LNG, Prince Rupert) project is a prime example of what’s wrong with Canada’s approach to engaging Indigenous communities in large-scale industrial developments: It continuously fails to honour the legal obligations to Indigenous Peoples in protecting their traditional resources; The Canadian government generally consults with Band Councils, which were created under the colonial Indian Act, and often fails to consult hereditary leadership or respect traditional governance systems; …”

- Skeena Indigenous Groups Submission to UN CERD. July 6, 2017

It is interesting to note that only weeks after this report to the CERD was posted for the Session, Petronas announced its withdrawal from this proposed project, “Pacific NorthWest LNG.”

About the UNCERD:

The International Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Racial Discrimination was adopted in UN General Assembly in 1965, and entered into force on January 4, 1969.

The Committee is the treaty body which oversees compliance, receiving reports from states and civil society; meeting with states parties at UN headquarters to discuss their progress; and making observations that other states and corporations take into consideration.

The Convention, among all the UN treaties, establishes certain human rights norms which are considered essential for fulfillment of the goals of world peace identified in the UN Charter.

Colonialism, for instance, is identified as a threat to world peace in that Charter.

The CERD includes clarification in the preamble like,

Considering that the United Nations has condemned colonialism and all practices of segregation and discrimination associated therewith, in whatever form and wherever they exist, and that the Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples of 14 December 1960 (General Assembly resolution 1514 (XV)) has affirmed and solemnly proclaimed the necessity of bringing them to a speedy and unconditional end,

Convinced that any doctrine of superiority based on racial differentiation is scientifically false, morally condemnable, socially unjust and dangerous, and that there is no justification for racial discrimination, in theory or in practice, anywhere,

and provisions like,

Article 2, 1.a)

Article 2 1.(a) Each State Party undertakes to engage in no act or practice of racial discrimination against persons, groups of persons or institutions and to ensure that all public authorities and public institutions, national and local, shall act in conformity with this obligation;

(b) Each State Party undertakes not to sponsor, defend or support racial discrimination by any persons or organizations;

(c) Each State Party shall take effective measures to review governmental, national and local policies, and to amend, rescind or nullify any laws and regulations which have the effect of creating or perpetuating racial discrimination wherever it exists;

(d) Each State Party shall prohibit and bring to an end, by all appropriate means, including legislation as required by circumstances, racial discrimination by any persons, group or organization;

Article 5

…equality before the law, notably in the enjoyment of the following rights:

(a) The right to equal treatment before the tribunals and all other organs administering justice;

(c) Political rights, … (v) The right to own property alone as well as in association with others;

The UN treaty bodies play a key role in international human rights law. Many international conventions joined by members of the UN Charter have Committees attached to the treaty, and they review the states on a five-year cycle to monitor compliance and implementation. Other treaty bodies pertain to the Convention Against Torture; the Convention on Civil and Political Rights; the Convention on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights; and so on.

Canada is not a member of the Global Alliance of National Human Rights Institutions, formed in 1993. Of the 192 member states in the United Nations, 110 of them have National Human Rights organizations with membership in GANHRI. The Global Alliance works in concert with the United Nations system, mobilizing human rights education and development within states.

Canada’s next review in Geneva, UN Headquarters, is in March 2026 with the Committee on Civil and Political Rights. The Committee for the CCPR has presented some informed questions to Canada, ahead of its review, about the implementation of Indigenous Peoples’ rights to self-determination. The reports that Canada has posted ahead of the meeting only mention Indigenous communities in terms of health measures that were taken during the COVID pandemic: to prevent transmission of the virus and promote safe operation of schools and daycares; emergency funding for basic needs; and “additional supports to Canada’s network of existing shelters on reserve and in Yukon to help manage or prevent outbreaks in their facilities.”

You can find out more about the UN system at www.ohchr.org

Quotable Concluding Observations of the CERD:

CERD/C/CAN/CO/18, 25 May 2007

21. While welcoming the commitments made in 2005 by the Federal Government and provincial/territorial governments under the Kelowna Accord, aimed at closing socio-economic gaps between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Canadians, the Committee remains concerned at the extent of the dramatic inequality in living standards still experienced by Aboriginal peoples. In this regard, the Committee, recognising the importance of the right of indigenous peoples to own, develop, control and use their lands, territories and resources in relation to their enjoyment of economic, social and cultural rights, regrets that in its report, the State party did not address the question of limitations imposed on the use by Aboriginal people of their land, as previously requested by the Committee. The Committee also notes that the State party has yet to fully implement the 1996 recommendations of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (art. 5 (e)).

In light of article 5 (e) and of general recommendation no. 23 (1997) on the rights of indigenous peoples, the Committee urges the State party to allocate sufficient resources to remove the obstacles that prevent the enjoyment of economic, social and cultural rights by Aboriginal peoples. The Committee also once again requests the State party to provide information on limitations imposed on the use by Aboriginal people of their land, in its next periodic report, and that it fully implement the 1996 recommendations of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples without further delay.

22. While acknowledging the information that the “cede, release and surrender” approach to Aboriginal land titles has been abandoned by the State party in favour of “modification” and “non-assertion” approaches, the Committee remains concerned about the lack of perceptible difference in results of these new approaches in comparison to the previous approach. The Committee is also concerned that claims of Aboriginal land rights are being settled primarily through litigation, at a disproportionate cost for the Aboriginal communities concerned due to the strongly adversarial positions taken by the federal and provincial governments (art. 5 (d)(v)).

In line with the recognition by the State party of the inherent right of self-government of Aboriginal peoples under section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982, the Committee recommends that the State party ensure that the new approaches taken to settle aboriginal land claims do not unduly restrict the progressive development of aboriginal rights. Wherever possible, the Committee urges the State party to engage, in good faith, in negotiations based on recognition and reconciliation, and reiterates its previous recommendation that the State party examine ways and means to facilitate the establishment of proof of Aboriginal title over land in procedures before the courts. Treaties concluded with First Nations should provide for periodic review, including by third parties, where possible.

CERD/C/CAN/CO/21-23, 25 August 2017

Truth and Reconciliation Commission and UN DRIP

17. While welcoming the commitment made to implement all of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s (TRC) 94 Calls to Action, the Committee is concerned at the lack of an action plan and full implementation. The Committee is further concerned that the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UN DRIP) Action Plan has not yet been adopted, while noting the Ministerial working group established in 2017 to bring laws into compliance with obligations towards Indigenous Peoples.

18. The Committee recommends that the State party:

(a) Develop a concrete action plan to implement the TRC’s 94 Calls to Action, in consultation with Indigenous Peoples.

(b) Implement the UN DRIP, and adopt a legislative framework to implement the Convention including a national action plan, reform of national laws, policies and regulations to bring them into compliance with the Declaration, and annual public reporting.

(c) Ensure that the action plans include regular monitoring, evaluation, and annual reporting of the implementation, including the use of statistical data to evaluate progress.

(d) Develop and implement training programs, in consultation with Indigenous Peoples, for State officials and employees on the TRC’s Calls to Action and the UN DRIP, to ensure their effective impact.

(e) Ensure that the Ministerial working group is transparent and inclusive of Indigenous Peoples. Land rights of Indigenous Peoples

19. Taking note of the recent release of a set of 10 Principles Respecting the Government of Canada’s Relationship with Indigenous Peoples in 2017, the Committee is deeply concerned that:

(a) Violations of the land rights of Indigenous Peoples continue in the State party, in particular environmentally destructive decisions for resource development which affect their lives and territories continue to be undertaken without the free, prior and informed consent of the Indigenous Peoples, resulting in breaches of treaty obligations and international human rights law.

(b) Costly, time consuming and ineffective litigation is often the only remedy in place of seeking free, prior and informed consent, resulting in the State party continuing to issue permits which allow for damage to lands.

(c) According to information received, permits have been issued and construction has commenced at the Site C dam, despite vigorous opposition of Indigenous Peoples affected by this project, which will result in irreversible damage due to flooding of their lands leading to elimination of plants medicines, wildlife, sacred lands and gravesites.

(d) According to information received the Site C dam project proceeded despite a joint environment review for the federal and provincial governments, which reportedly concluded that the impact of this dam on Indigenous Peoples would be permanent, extensive, and irreversible.

(e) According to information received the Mount Polley mine was initially approved without an environment assessment process, consultation with or free, prior and informed consent from the potentially affected Indigenous peoples, and that the mining disaster has resulted in a disproportionate and devastating impact on the water quality, food such as fish, fish habitats, traditional medicines and the health of Indigenous Peoples in the area (art. 5-6).

20. Recalling its general recommendation No. 23 (1997) on the rights of Indigenous Peoples and reiterating its previous recommendation (CERD/C/CO/19-20, para. 20) the Committee recommends that the State party:

(a) Ensure the full implementation of general recommendation 23, in a transparent manner with the full involvement of the First Nations, Inuit, Metis and other Indigenous Peoples with their free prior and informed consent for all matters concerning their land rights.

(b) Prohibit the environmentally destructive development of the territories of Indigenous Peoples, and allow Indigenous Peoples to conduct independent environmental impact studies.

(c) End the substitution of costly legal challenges as post facto recourse in place of obtaining meaningful free prior and informed consent of Indigenous Peoples.

(d) Incorporate the free, prior and informed consent principle in the Canadian regulatory system, and amend decision making processes around the review and approval of large-scale resource development projects like the Site C dam.

(e) Immediately suspend all permits and approvals for the construction of the Site C dam. Conduct a full review in collaboration with Indigenous Peoples of the violations of the right to free prior and informed consent, treaty obligations and international human rights law from the building of this dam and identify alternatives to irreversible destruction of Indigenous lands and subsistence which will be caused by this project.

(f) Publicly release the results of any government studies of the Mount Polley disaster and the criminal investigation into the disaster, before the statute of limitations for charges under these Acts expires.

(g) Monitor the impact of the disaster on affected Indigenous Peoples as a result of the disaster, and take measures to mitigate the impact through provision of safe water and food, access to healthcare, and fair remedy and reparations.