Tags

aboriginal rights, aboriginal title, Federal Liberals Comprehensive Claims Policy, Indigenous Peoples, Land claims, Reconciliation

Part 5 of this week’s blog, No More “Reconciliation Sticks”

In the 1970s, at least one informant in the Canadian government was relaying the state’s plans to Indigenous political leaders.

The obvious question is, why did the Governors Attorney and General, the Superintendents, judges and Ministers have secret plans?

In one easily cracked nutshell, the Canadian state was already wildly liable for attacking the British Crown’s “Allies; the Tribes and Indian nations with whom We are Connected” – and fur trading partners – in their own protected territories, so peace and good faith would be hard to recover. And because, in the case of the Colony of British Columbia, the British wouldn’t give them any money for Treaties. So the politicians and judges could not very well speak out about what they had in mind – at least not plainly.

The many-headed word “reconciliation” aids them there.

In Canada, it has taken three centuries of brutal tactics, and the martial law of Indian Act Band Councils, and the colony has still not convinced the nations to become consenting colonial districts.

Today, Canada is more desperate than ever to manufacture this consent.

Using the “concept of reconciliation,” among many coercive tactics, a replacement Indian Act targets Indigenous communities under duress.

Attempting to transform constitutionally and internationally protected peoples, owners of rich and substantial land bases, into virtually landless provincial municipalities, Canada has passed into law an entire framework to replace the Indian Act. You may remember the First Nations Governance Act, revised; the First Nations Fiscal Accountability Act; the First Nations Land Management Act, et al, as the omnibus Bill C-45, 2012, which sparked the Idle No More protests.

The crucial difference with this municipalization plan, is that the present day First Nations’ entry into confederation would be achieved by consent. Consent to the state and recognition of “crown interests” are achieved incrementally in delegated jurisdiction agreements concerning education, child welfare, housing, health, and such; as well as in negotiation of land claims under the 1974(78) Comprehensive Claims Policy and the 1995 Inherent Rights Policy (the leading extinguishment programmes in Canada today),

There, reconstituted under Canadian law – having ratified an individual First Nation constitution; having released and indemnified the colonizers; having accepted cash as the full and final settlement of Aboriginal rights – the First Nations will be outnumbered in provincial unions of municipalities. There, First Nations will be dependent on five-year provincial funding agreements and occasional aid for natural disasters, and will not retain their autonomy, or sovereignty, or even those controversial Aboriginal rights.

Today’s article looks at the mechanism of the “concept of reconciliation” at play in the municipalization of Indigenous communities. Municipalization is the only future, under Canada’s runaway judges, consistent with their regularized practice of complete abrogation and derogation from “Aboriginal and treaty rights.” It is the only possibility that conforms to the reconciliation program, as described by the Supreme Court of Canada.

It will not be achieved by any means consistent with the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

But hey, if First Nations want to make Final Agreements that extinguish their rights, who’s to stop them.

From unilateral legislation to coercion

So, in the 1970s, Walter Rudnicki was working for the federal government. He shared confidential information with the leaders of the Union of BC Indian Chiefs. He confirmed the intention of Canada to finally coerce the assimilation of every Indian Band as a provincial municipality, and thereby liberate itself from the burden of acquiring title. A consensual union would also indemnify the state of past harms.

Here’s the setting.

The legendary 1969 White Paper, the Statement of the Government of Canada on Indian Policy, had just failed spectacularly up: forging extensive political allegiances from coast to coast to coast. It had been a play to unilaterally assimilate the nations by legislation, demolishing the Indian Act and every line of constitutional ink that described the burden of legally acquiring title to the Indian territories.

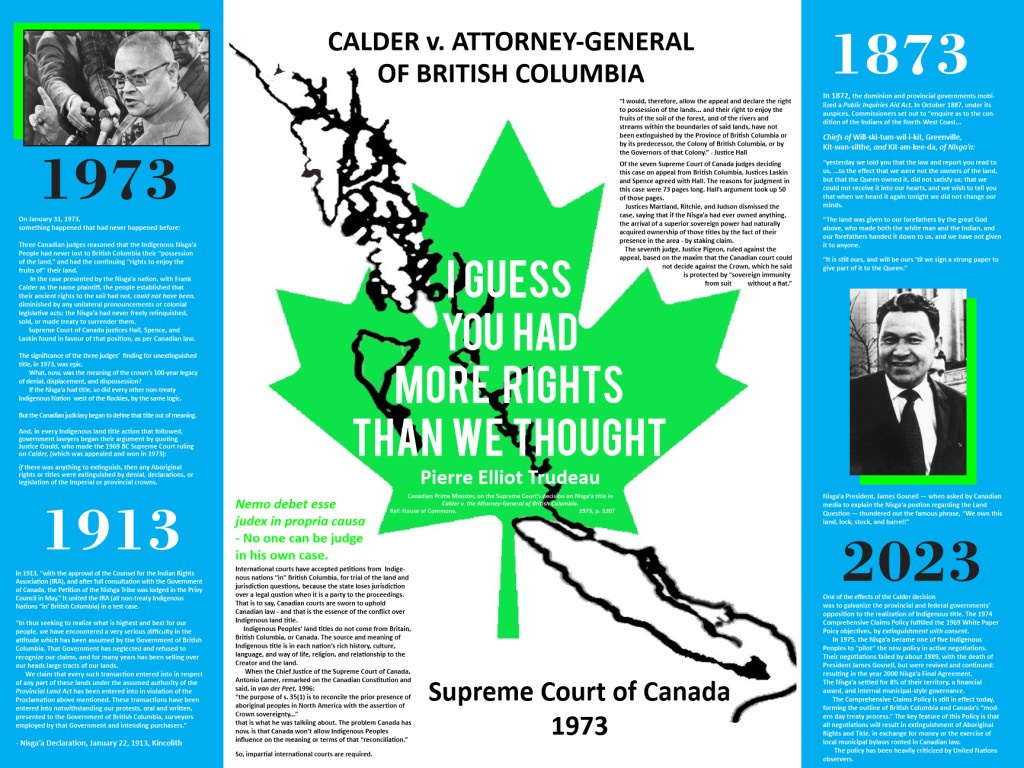

The Nishga case, Calder v. The Attorney General of British Columbia, got a 1973 admission from the Supreme Court of Canada that Aboriginal title continues to exist in Canada, unextinguished.

Trudeau the First and his Minister of Indian Affairs, Jean Chretien, passed the federal Comprehensive Claims Policy within the year. Any Indigenous nation could apply within the process it enabled, and they could get small cash and smaller land deeds as a final settlement of their title, rights, and interests in the surrendered area.

The Comprehensive Claims Policy, 1978 update, is the leading negotiating policy today.

Indigenous leaders did not particularly need an inside informant to confirm the meaning and intent of that. But it may have been helpful, in some cases, to have a little advance warning of the next strategy being formulated.

It was helpful in 1981, in the case of Trudeau’s next best plan, the attempt to get a new Constitution from Britain: one which did not include any obligations to the now occupied nations.

It was helpful in 2009, when British Columbia had tried to simply legislate the Bands under provincial jurisdiction.

Someone gave the Union of BC Indian Chiefs a copy of the September, 2004 “Secret Framework for Renewing Canada’s Policies with Respect to Aboriginal and Treaty Rights.” Emphasis in the original.

The draft Framework begins by reminding us that the Speech from the Throne, April 2004, stressed finding more efficient ways of concluding self-government agreements. (Self-government means municipalization under Canadian law and abandonment of original Indigenous titles and jurisdictions, at least the way Canada uses the term.)

It mentions the “sectoral follow-up table on expediting land claims,” which are “a key component for transforming relationships.” (That is, until First Nations abandon original claims and accept delegated Canadian authorities in Final Agreements, they won’t get any.)

It says,

“The Speech from the Throne and the establishment of the sectoral table on land claims and self-government reflects the reality that establishing cooperative relationships with Aboriginal peoples on quality of life issues must be underpinned by effective policies and processes for addressing Aboriginal and treaty rights.” (That is, there won’t be any improvement in on-Reserve quality of life until extinguishment agreements are signed – as above.)

The Aboriginal participants at the same sectoral follow-up voiced the exact opposite set of priorities:

“Aboriginal groups emphasized that joint work on quality of life issues must be situated in the broader transformative agenda based on recognition and respect for Aboriginal and treaty rights.”

The secret draft writers resolved that stitch by reminding the secret reader,

“The Supreme Court of Canada has stated that the basic purpose of section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982, is the reconciliation of the pre-existence of Aboriginal societies with the sovereignty of the crown. Reconciliation has become the key organizing principle which the courts have used in addressing issues related to Aboriginal and treaty rights.” (That is, the court has taken the political lead and reduced legal rights to issues, so the government’s job is just to follow suit.)

Note: We looked at that in Part 2 – Theft by Chief Justice, where the term “reconciliation” was coined.

The 2009 British Columbia “Recognition and Reconciliation Legislation” was crafted under Premier Gordon Campbell and his cabinet of hungry skeletons, particularly Mike deJong, Wally Oppal, and former QC Geoff “they never had any title and if they did it was extinguished by the presence of the crown” Plant.

This legislative flop was certainly influenced by the 2004 secret plan – if nothing else, it must have been lent audacity. The province’s 2009 Re&Re Legislation even came with sign-off from the First Nations Leadership Council (FNLC)[i] and their lawyers from Mandell Pinder.

Only thing was, the FNLC hadn’t mentioned anything about the legislation to its members, or their respective peoples and constituents, when the right honourable Mike deJong announced to media the “seismic shift” that was about to occur in BC.

And consent is sacrosanct. The bluff was called, retracted, and turned to ash – like the White Paper Policy 1969.

The government’s only working plan now is coercion.

Instead of consent, all these years, there’s only forcible imposition

Canada has forcibly imposed the Indian Reserve and Indian Band structures – on non-treaty and treaty nations alike.

British Columbia plays a huge part in the necessity that mothered that invention.

The province of BC was written into existence in 1858, unbeknownst to any Indigenous leaders west of the Rockies, by the Queen of the British Empire – precisely one-half the circumference of the globe away. Then she forgot about it, and nobody in England wanted to pay for treaties there.

There is no need for me to re-write what happened once the Indigenous protest reached a critical level. This is from Bruce Clark’s “The Error in the Tsilhqot’in Case,” 2018:

“In 1874 British Columbia enacted a Crown Lands Act that regarded all crown land as if it were public land available for disposition, even though the land is part of the continental reserve for the Nations or Tribes of Indians, not being “ceded to, or purchased by Us.” In a report to the Canadian Privy Council, Attorney General Télésphore Fournier recommended disallowance under section 90 of the Constitution Act, 1867, on the ground of conflict with the proclamation and section 109. The report was approved in a Minute in Council dated 23rd January 1875 and endorsed by the Governor General.”

“British Columbia then made a proposal to Canada to resolve the Indian problem by establishing a commission to investigate and “set apart” provincial Crown lands as “reserves” for Indian use. This led directly to the Indian Act, 1876. The Acting Minster of Interior Affairs in a report dated 5th November 1875 recommended approval of the provincial plan, which was done by the Canadian Privy Council pursuant to Minute in Council dated 10th November 1875. This entailed leaving the originally disallowed Crown Lands Act to its operation, i.e., reviving it. Attorney General Fournier was elevated to the Supreme Court and was replaced in office by Attorney General Edward Blake. Blake reported under letter dated 6th May 1876 to the Governor General explaining that “Great inconvenience and confusion might result from its disallowance.” As recommended, on second thought, the Governor General did leave the statute to its operation. Treaties were not made thereafter in mainland British Columbia. There was no need, since all Crown land was thereafter unconstitutionally regarded as public land available for disposition. It was as if the Royal Proclamation of 1763 and the “subject to” proviso in section 109, BNA Act, duly had been repealed or had never existed.”

When Canada passed the Indian Act, everything an Indigenous nation would need to do to survive was criminalized. In the legislation, Indians were defined negatively as “a person is anyone other than an Indian.”

If Indigenous Nations didn’t consent to be governed by the Indian Act, why go along with it?

Because someone had to take those roles in the leadership and administration of the office; in the Band Council.

No, they really had to.

You can’t have an economy based on the resources in a few acres of Indian Reserve, and you’re not allowed to sell anything anyway. Not even vegetables or produce, when it makes competition for settlers at their markets.

In 1935 the Indian Act was amended to reflect that there must be one (1) Chief Counselor per Band, and that he should be elected by popular vote, in the prescribed fashion. This did not resemble any Indigenous structures.

But without that, the Band can not receive the relief funds provided by the government which took their land. That relief program started approximately at the time the plains peoples were starving because the settlers wiped out the buffalo… to make sure they would starve.

In BC, it started in 1927, after DC Scott and his colleagues in the Judicial Committee, in Ottawa, dismissed the Claims of the Allied Indian Tribes, formally. The relief was the “BC Special” – $100,000 per year, “In lieu of treaties.”

There were more than 200 Bands at that time. The <$500 per Indian Band per year, a pittance – and most of it paid to the Minister of the Interior to administrate the fund, hasn’t quite kept up with inflation here in 2023.

This is what makes things like “economic reconciliation” sound attractive to First Nations. This is how “the reconciliation of aboriginal societies with the sovereignty of the crown” is achieved: under duress.

Pitawanakwat, 2000

In an Oregon County court, Justice Stewart compared OJ Pitawanakwat’s situation in Canada with members of the Irish Republican Army in Ireland. She found it was manifestly the same. Just as Spain refused, in the 1990s, to extradite IRA members to Britain, Justice Stewart refused Canada’s extradition request.

Pitawanakwat was present at the Gustafsen Lake police siege, 1995, and had subsequently been charged, detained, and released on bail after two years. He fled to the USA.

Now, because of the facts that “his conviction was of a political character,” and in a “politically charged climate,” were recognized by an American judge, he lives there still, unable to return home to Anishinabek territory.

At Gustafsen Lake, they said no to the Indian Act; they said no to municipalization; and they said no to extinguishment in full and final settlements. The Attorney General declared war on them.

“We’re not going to agree to anything that will affect our economy.”

Thus spake the province’s negotiator at the St’át’imc Chiefs Council protocol table, in 2008. He might as well have been speaking on behalf of the Canadian state.

The “reconciliation” proposed by Canada would be achieved, if ever, because it is the only prescription for change that Canada will agree to. And that change is: Indigenous nations must submit to their bisection and reduction to scattered postage-stamp communities, where less than a quarter of their own Band membership has room (or housing) to live. They also must relinquish all claims against the province, the state, and “anyone else” for past harm. They must reconstitute themselves, starting with a new Constitution for each First Nation, and enter the hallowed halls of the Union of BC Municipalities.

The conditions under which that kind of “consent” would be achieved, would not hold up under international scrutiny.

It would be achieved under a colonially imposed, extra-legal regime, rather than by authentic governance procedures. It would be achieved by denying Indigenous titles, and capitalizing on the financial ruin which has resulted from this. It would be achieved by refusing to recognize authentic and legitimate holders of the rights to political decisions, who can be marginalized by the imposed ratification procedures.

But, to the great credit of humanity – which will go down in history forever – Indigenous Peoples may be cash poor, but they’ll surely survive these lean, mean years and live their own way.

Thank you very much for reading. Takem i nsnukw’nukw’a.

[i] Executives of the First Nations Summit (BC Treaty Process); Assembly of First Nations (BC region); and Union of BC Indian Chiefs.