The Human Rights Committee questioned Canada in twenty different areas concerning the human rights of Indigenous Peoples.

The United Nations Committee members were “alarmed” by a number of basic Indigenous statistics and determined to find out “why” the state does not legislate constitutionally protected aboriginal and treaty rights; “how” the state was going about improving education and health outcomes; “what” targets the state has set for reducing Indigenous poverty; “when” the state would respond to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Call to Action; “who” was being prosecuted and investigated for the widespread violent crimes against Indigenous women and girls; “where” aboriginal titles are being recognized and affirmed.

But the state did not answer any of those questions directly.

Over the course of two public meetings, July 7th and 8th in Geneva, Canada’s lack of compliance with the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (CCPR) was exposed and explored. The state’s contempt for the Covenant, refusal to acknowledge its application in Canada, and naked disinterest in making any attempt to meaningfully live up to the standards of this human rights instrument – which it ratified in 1949, where Indigenous Peoples’ rights are concerned, were literally confirmed by Canada’s delegation itself.

Indigenous Peoples have given everything to the struggle for their future and the sustainability of their lands and cultures, and they have also given the Committee a lot of detailed information about their struggle which informed the interview this week. This article is a point-by-point review of the questions which were asked of Canada and the answers, redirections, or silences, that were provided in response.

The Committee created a List of Issues (LOI) for Canada to respond to, and Canada provided a written response three weeks before the formal, public meeting where these further questions were asked.

Many Indigenous nations and peoples do not participate in this process because they do not agree that Canada has the right to report on them, as if they were a minority population within Canada’s citizenry, to the treaty bodies. These nations would like a place for themselves, to ratify the Covenants when appropriate and to speak to the treaty bodies about their own nation’s implementation of international human rights law.

Many Peoples did participate in hopes of promoting international recognition of Indigenous Peoples’ rights beyond the minority rights outlined in Article 27 of the Covenant, where Canada reports on them, to the more appropriate peoples’ rights outlined in Article 1. The first and second paragraphs of CCPR confirm the rights of all peoples to self-determination; to freely dispose of their natural wealth; to never be deprived of their own means of subsistence; and to freely determine their political status. Unfortunately the Committee did not make this leap and concerned itself mainly with Aboriginal rights, as defined by Canada, in the following areas.

The “precarious situation” of Aboriginal peoples in Canada

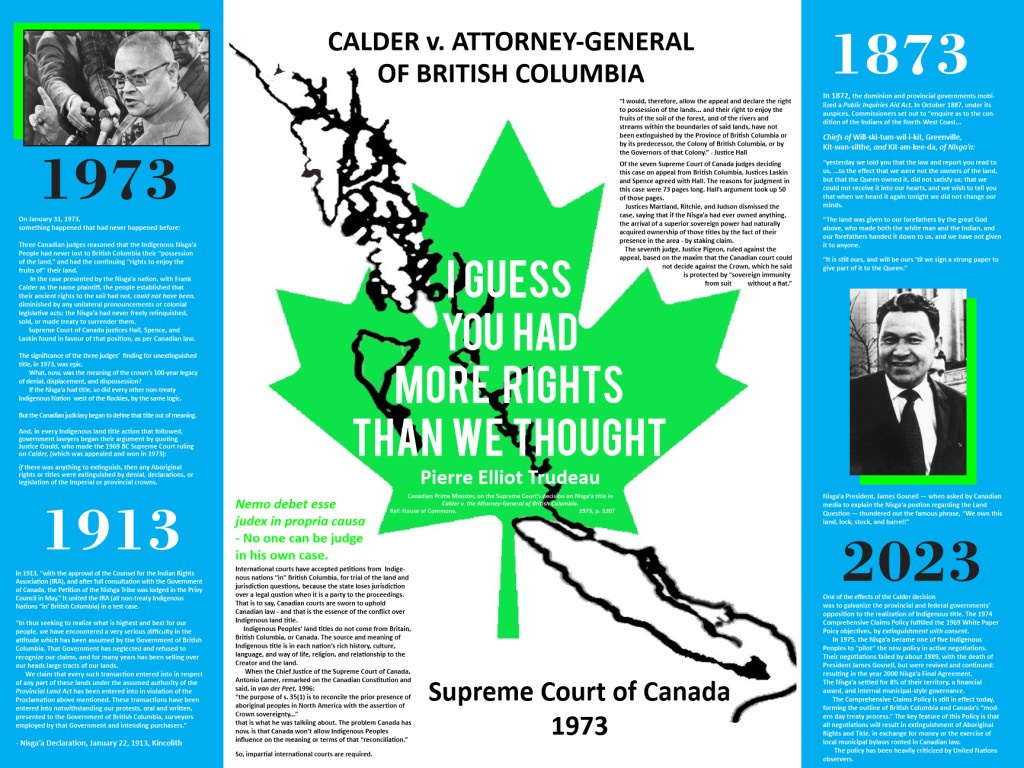

Land rights, Constitutional rights, and Aboriginal title:

“I fail to understand why constitutionally protected aboriginal rights are not specifically defined in legally enforceable terms.”

Questioning the uncertainty and lack of access to justice faced by Aboriginal peoples, several Committee members asked for clarification of Canada’s written response.

“There are concerns that disputes over Indigenous peoples’ rights to benefit from and control lands are continuing,” Dr. Anja Seibert-Fohr reiterated LOI Questions 19 and 20. “Part of the problem appears to me to be the uncertainty of the scope of aboriginal titles and rights. I fail to understand why constitutionally protected aboriginal rights are not specifically defined in legally enforceable terms.”

Dr. Seibert-Fohr was following up on a request for clarification made by Committee Member Margo Waterval: “What do you mean when you say Aboriginal court cases take a long time “due to the complexity of Aboriginal law and the interests at stake”?

Frank Wheldon[i] of the Canadian delegation had answered: “Section 35 of Canada’s Constitution recognizes and affirms aboriginal and treaty rights, but they’re not specifically articulated. The Canadian courts have provided guidance to interpret that section and identify those rights as well as justifiable limitations on those rights. With that said, defined aboriginal rights are specific to an aboriginal group. In that sense, one finding of aboriginal rights does not mean that other aboriginal groups have that right. Every case is a new case. And in each of those cases there are questions of title, harvest, rights to consultation. So, recognizing the delays before a judicial resolution, the government much prefers addressing those issues through negotiation rather than letting them get to court.”

Dr. Seibert-Fohr continued her question to Canada: “It appears the “case by case” approach is the very reason for the difficulties and uncertainties faced by Aboriginal peoples. I can understand the reluctance around creating fixed definitions of titles, for fear it might limit the application of future developments, but we are all lawyers here and we know how those eventualities can be addressed.”

“But without such clarification, it is difficult to rebut the assertion that the state attempts to extinguish Aboriginal rights, and not to honour historical treaties and arrangements.”

Wheldon addressed this very accurate observation as follows: “As elegant as it may be to articulate and implement rights uniformly, what has come back to us is the diversity of rights and diversity of circumstances in which those rights are claimed, which does not lend itself well to specific articulation of rights. Government favours establishment of land claims or modern treaties with Aboriginal groups.”

“Associated with that question was extinguishment. It is in reality a question of a clarification of rights and creation of certainty. There are a range of certainty techniques (he says there are too many to mention), but the objective associated with this is to articulate rights for certain groups. These rights can evolve over time, this is a practice recently introduced into negotiations around Section 35 rights.”

It is a fact that in the early days of the BC Treaty Commission their website featured a glossary. Under the entry “certainty,” it said “See extinguishment.” And nothing about that has changed.

The unqualified remark about evolving treaty rights must be checked: only rights pertaining to law making powers, or civil, social, cultural rights, may evolve. Land rights and rights to resources are specifically exempted from any evolution post-Final Agreement, according to the federal government’s commissioned study by Douglas Eyford, “A New Direction: Advancing Aboriginal and Treaty Rights.”

Missing and murdered women, violence against Indigenous women and girls and… domestic violence?

The Committee spent a great deal of energy asking and repeating questions to the state delegation to get information about whether there would be a national inquiry into the missing and murdered women and how, for example, the Pickton murders continued unchecked for so long. They asked what the state is doing to address the high levels of violence against Indigenous women and girls, “and my question is not only about impunity, it’s structural. What is the state doing to address this elevated level of violence against Aboriginal women in society at large?” They asked, repeatedly, whether the recommendations made by visiting human rights bodies, the report by the Committee for the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) and the report of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) would be implemented, and how and when that would take place.

Canada’s response was not immediately believable, and Committee members repeated their questions during the first opportunity for follow-up.

The Canadian representative said, “I’ll be speaking to statistics from an RCMP perspective.” She read from the 2014 RCMP national overview report, and came to an unexpected conclusion. The Committee was told that Canada would be launching an extensive action plan, in fact it had been launched in April this year, featuring the key elements of addressing domestic violence on reserves, building more shelters for victims of domestic violence, supporting families with getting information on cases of missing women, and delivering programs for men and boys to help them stop acting out intergenerational displays of abuse.

Once the Canadian delegation was invited to respond to the follow up questions, the same questions as were asked in the first place were repeated, the Canadian delegate repeated her list of action items grounded in the RCMP’s 2014 report – support for victims, community based programs aimed at domestic violence, and better information sharing with victims’ families.

The question of implementation of the IACHR or CEDAW reports was not broached, not until Martha LaBarge, Canadian Heritage, touched on the matter of the Human Rights Committee’s rightful ability to give Canada direction on Civil and Political Rights implementation – being the treaty body constituted by the Covenant, populated by independent experts, and therefore capable of making recommendations to states.

LaBarge responded to the Committee’s questions about how Canada views the Committee and its recommendations; whether the state intended to act on the forthcoming concluding observations which it is about to offer the state. She noted that there has not been a First Ministers’ conference since 1988. “We may have another one soon. This may help Canada receive and use the recommendations of the UN, including the IACHR report on missing and murdered women.”

LaBarge elaborated on the Missing Persons Acts of British Columbia and Manitoba, carefully explaining police protocol and special powers in the case of a missing person, which, she said, “may include a missing or murdered Aboriginal woman.” British Columbia has developed standards for reporting a missing person, effective in 2016. There is also state support for bias-free policing.

Canada’s response to the most outrageous, long-term ongoing crimes against Indigenous Peoples on the most painful subject of their oppression, the violence against the women and girls by non-Indigenous men who dump their bodies in shallow graves, was stunning in its bald refusal to address the questions being put directly to it. Questions the RCMP themselves, not their 2014 report, helped form by their well-known complicity in ensuring impunity for perpetrators of this kind of crime, if not actively participating themselves. The Oppal Commission featured a Coquitlam cop who couldn’t help staging the abduction of a dark haired woman from the downtown Eastside of Vancouver, and then a series of torture pictures, all while working directly for the BC Commission of Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Women.

Canada’s refusal to acknowledge the depth and breadth of this issue may be one of the most revealing actions of the “systemic discrimination” reported by the IACHR earlier this year.

The state representative named only “Jessica” (Laurie Wright, head of the delegation, did not introduce her colleagues especially extensively), told the Committee: “Canada has already provided the Committee with extensive reports and information on programs to address and prevent these crimes, including the RCMP overview which provides facts on which to base ongoing efforts.” She added information about a $200million program over five years to build shelters and carry out the “priorities” mentioned above by the state delegation. A new program for victims of violence “nationwide” has earmarked $30 million of a total $100 million over ten years to go to First Nations and Inuit health – that fund is now receiving applications from organizations that deal with domestic and family violence.

A Canadian delegate named (approximately) Lily Paul Nieuwe explained the “third government plan of action, 2012-2017, to address domestic violence and children exposed to it. This plan includes measures for aboriginal people. The plan is the result of broad consultations by government with 75 organizations, including women’s groups and Aboriginal women’s groups.”

The plan is apparently designed “to meet the needs of Inuit and First Nations; older persons; members of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender communities; as well as men who are victims.” Lily Paul says building shelters is an urgent priority: “there are only one hundred shelters in Quebec, which is an aboriginal area.”

Miss Waterval had been one of the first Committee members to question Canada on the level of violence against Indigenous women: “You stated the RCMP released a national operational overview; so what was the legislation adopted in British Columbia and Manitoba in response to the report? And you did not answer, in the written report, the number of investigations, prosecutions and sanctions imposed in cases of disappearance and murder of Aboriginal women. Please reply to that. And is it true that most disappearances and murders remain unsolved?”

Legislation which impacts Aboriginal peoples, without consultation

Dr. Seibert-Fohr: “Could the delegation explain specific cases of consultation with Aboriginal peoples regarding the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act, the National Energy Board Act, the Fisheries Act, the Navigable Waters Protection Act, and the Jobs and Growth Act.* What remedial measures have been taken since the complaints we have heard that there were no consultations on changes to those federal Acts?”

The Indian Act was also referenced in the context of the report of the Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples’ visit to Canada in 2013. “The Indian Act was described as a rigidly paternalistic law at its inception, which structures aspects of Canada’s relationship with Aboriginal peoples.” The Committee expressed the view that amendments to the Indian Act have not remedied sex discrimination in the Act, where male Status Indians’ grandchildren have full Status but female Status Indians’ grandchildren have second-class Status.

Wheldon replied to this, “The government is committed to an incremental approach to reform and to give First Nations more control over their day to day affairs.” The state representative indicated that there are too many recent changes to the Indian Act to mention but that these are easily accessed (online). He redirected the Committee’s attention to the recent adjustment of the Indian Act to recognize the matrimonial property rights of women on Indian Reserves, and then replied to the “number of issues regarding discrimination in the Indian Act. Bill C-3 was a significant step forward for that. A Special Rapporteur has been appointed by the Minister to look into grievances in the registration process.” He characterized this form of resolution as an ongoing process, with discussions ongoing.

Abiding the Human Rights Committee, in Canada

At least three of the Canadian delegates repeated the statement that the CCPR has no force or application in Canada. This Covenant was ratified by Canada in 1949, and the government’s website indicates compliance with international human rights treaty bodies.

In his closing remarks, the Chair of the Committee reminded the assembled that it is the Treaty Body’s interpretation of the issues at hand, and their concluding observations and recommendations, which carry weight; not the state party’s interpretation of those observations.

Deprivation of liberties of persons of Aboriginal heritage

Canada readily agreed the number of Aboriginal inmates in prisons is disproportionately high compared to the Aboriginal population in Canada. When asked how the state was addressing this over-representation, Canada’s delegation told the Committee they were building more facilities to hold all the prisoners. They said the same thing in response to the Committee’s “alarm” at the high rate of Aboriginal youth in prison. The Committee’s question was presumably aiming at how the state would address the root causes of the criminal activity, obvious causes like poverty and powerlessness, and thereby decrease participation in the criminal justice system.

The committee member’s question, pursuant to an area of the LOI, was: “In view of the statistical over-representation of Indigenous people in jails, and that statistic on the rise, please describe the effectiveness of the programs put in place. What measures has the government taken with Aboriginal communities to prevent over-representation?” Miss Cleveland asked for this clarification, and continued, “What steps are taken to implement alternatives to imprisonment?” She echoed the earlier written request for disaggregated data on Aboriginal individuals who had benefitted from community-based corrections. Noting the over-representation of Aboriginal women in prison, she asked for data on those numbers since 2013 and asked, “how many are in maximum security? How does this compare to the classification of non-Aboriginal female prisoners in maximum security? What steps are taken to address this?”

The state did not reply.

The Committee was informed that in Canadian prisons, “disciplinary segregation” has a maximum extent of 30 days, for one offense (committed while in detention), or 45 days for multiple offenses. This information is not, however, consistent with incidences of segregation and solitary confinement which, although these matters were not raised in the CCPR review, are reported to be a regular Aboriginal experience in Canadian prisons. According to a recent report by CBC news, some Aboriginal inmates at the Regina Correctional Centre are confined to their cells 21 hours a day sometimes for months and even years. One former inmate did not set foot outside for several years.

Meanwhile, the Committee was told that the Corrections Release Act provides a framework for engaging with Aboriginal communities, and sections 81 and 84 of that Act allow that at any time, an Aboriginal inmate can be transferred to the care of a community. However, another recent CBC report indicates that nearly 85 per cent of aboriginal offenders are detained in federal prisons until they have served two-thirds of their sentences, at which time most offenders are entitled to statutory release, compared to 69 per cent of non-aboriginal offenders. Apparently, problems with securing housing and high caseloads for legal aid lawyers contribute to longer wait times for release of aboriginal inmates in federal prisons.

Committee members asked about the effectiveness of the Aboriginal Court Worker program and they were assured by the Canadian delegation that its clients have reported a satisfaction rate of over 95%; the program has reduced times for court processes and that courts themselves commend the program. Canada’s delegation stated that the Aboriginal Justice Strategy reaches 800 Aboriginal communities (“Aboriginal” includes Inuit, First Nations and Metis), and a recent review of the program shows recidivism among those who used it.

“Canada is committed to culturally appropriate (incarceration). Canada recognizes that Aboriginal people are over-represented at all stages of the criminal justice system, including as victims. Judges take into account an offender’s Aboriginal heritage and accompanying circumstances during sentencing.” While Aboriginal persons are in custody they have access to cultural programs, Elders’ visits, and community re-integration support. Canada continues to develop community based solutions.”

Poverty and Food Shortages

Mr. Wasawa: “The problem of food shortages among Aboriginal peoples has been raised. How does the state address this? The UN Special Rapporteur, James Anaya, reported alarming data on poverty among Aboriginal peoples. Does the state party have a specific target for poverty reduction in tackling this area?”

The state reply was delivered by Wheldon, who identified Canada’s first priority as the Nutrition North food subsidy program, which serves Inuit regions. This program has an annual budget of $60million and has recently been increased by $11million. “More broadly, regarding food security, it is addressed through a broad range of programs: Income Assistance on reserves; economic development initiatives, a framework set out on the economic development side; Aboriginal entrepreneurship programs and the development of Aboriginal human capital; development of Aboriginal assets; facilitating partnerships with other communities; strengthening the federal role in economic development: and there is the bedrock of strengthening Aboriginal food security.”

It is interesting to note that Article 1.b of the Covenant on Civil and Political Rights declares that “in no case may a people be deprived of their own means of subsistence,” and yet this is exactly what is being described by Mr. Wheldon. The total economic assimilation of Aboriginal communities. He does not mention anything about restoration of the decimated deer herds, salmon runs, or optimal berry producing areas.

UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

Frank Wheldon, Aboriginal Affairs, addressed the Committee’s questions about Canada’s approach to the Declaration: “Regarding the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Persons,” he began.

The state party’s deliberate and pervasive use of inaccurate and derogatory terms when referring to Indigenous Peoples deserves its own unique examination. The number of instances of misuse of the term “Aboriginal peoples” in Canada’s written response, for example: “Aboriginal peoples off reserve are eligible for programs and services available to all Canadians,” paragraph 111, makes any accurate use of the internationally legally defined term “peoples” absolutely meaningless.

The state representative’s reference to a non-existent Declaration on the rights of “Persons” was not well received by the otherwise silent public audience of about 60 people, but was rejoined with an uncontrolled fit of derisive laughter. It sounded like a deliberate insult.

Wheldon then said, “The Declaration is not legally binding nor does it reflect customary international law. We are in partnership with Aboriginal people to make a better Canada, within the framework of the Canadian constitution and the 2010 statement of support for the Declaration. It’s an aspirational document.”

The Aboriginal Title Alliance submitted an extensive report to the Committee with further information and documentation on the List of Issues, as well as a brief memorandum on the importance of Article 1 to Indigenous Peoples. The report was driving to the need to have Canada report on implementation of self-determination by Indigenous Peoples, not to continue reporting on each aspect of daily Aboriginal life as if the dozens of distinct nations were ethnic minorities needing program management.

The Indigenous Peoples and Nations Coalition delivered a message to the Committee regarding Canada’s public session. Referencing the Report to the General Assembly of Alfred de Zayas, the independent expert on the promotion of a democratic and equitable international order, the statement reminded the Committee that the Indigenous nations “in” Canada may be referred to the Special Committee on Decolonization. Referencing the report of Miguel Alfonso Martinez on Indigenous treaties and constructive arrangements, Ambassador Ronald Barnes reminded the Committee that the burden of proof is on the state to show how it acquired jurisdiction over Indigenous Peoples, and that they do have the right of Article 1, the right to self-determination and equality as peoples.

“Engagement”? Or “Consultation” and “Accommodation”… or “Consent”?

Free, prior, informed consent is one of the provisions in the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. The Declarations announces that Indigenous Peoples have the right to be so informed and to consent before any developments take place in their lands.

“When Canada issued its statement of endorsement (of the DRIP, in 2010) it reiterated concerns regarding the provisions of free, prior, informed consent.” Frank Wheldon, replying to one of Mr. Yuji Wasawa’s questions.

Mr. Wasawa prefaced his question by explaining that he is a former member of the Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, and during his time there he “learned a lot.” He asked a string of questions further to LOI #19.

“Canada was one of only four countries who voted against the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in 2007. However, in 2010 Canada endorsed the Declaration. What made the government change its position?

“It is reported that Canada endorsed the Declaration with many reservations. How does the state party view the Declaration now? Has it changed its policies in light of the Declaration? In particular, how does the State apply the principle of free, prior, informed consent with respect to lands development and impacts on Aboriginal communities?”

Dr. Seibert-Fohr: “We are aware that consent is not happening in all areas although the Supreme Court of Canada acknowledges this right. As a consequence, Aboriginal peoples are forced into long court processes to protect their rights. Is it true that the state allows developments to continue in cases where consent has not been acquired?”

“I wonder why the government uses the term “engagement,” there is no legal definition for that term, instead of “consultation”? And why is there no legal framework for consultations with Aboriginal peoples? We know there are frameworks for public consultations regarding environmental assessments, this could be possible for consultations with Aboriginal peoples too.”

Wheldon spoke to the majority of issues particular to Indigenous Peoples. “From a Canadian perspective,” he continued, meaningful consultation and accommodation is central to reconciliation, which” he then provided a familiar Supreme Court of Canada quote, “is part of the process of reconciling the pre-existence of aboriginal societies with the sovereignty of the Crown.”

“In Canada, consultation is a process by which the rights of Aboriginal people are taken into account. Canada believes in a process of consultation and accommodation where individuals and people are more fully involved and consulted where their rights and interests may be affected.”

“There are a range of consultation processes ongoing about the consultation process, to ensure adequate consultation with Aboriginal groups.”

“Growing tensions” between the state and Indigenous Peoples

“In Question #19.a, the Committee asked about the “growing tensions” between the state and Indigenous Peoples. Could the state delegation provide us with a more specific response,” Mr. Yuji Wasawa asked.**

Canada’s written response took Question 19.a as an opportunity to say that “The Government of Canada works closely with First Nations, Metis, and Inuit groups in Canada; specifically with separate Aboriginal representative organizations and other stakeholders, to address the different challenges and opportunities facing their communities.”

It is worth noting Canada’s clarification that it prefers to work with umbrella organizations – who are government funded and have no clear mandate from the voters whose elected community officials end up in “seats on the Board” out of habit or as per government expectation and accompanying per diem, as in the case of the Assembly of First Nations[ii]. The state mentioned the Crown-First Nations Gathering as an example of this good work.

The state party went on to describe how it is “working hard to ensure constructive engagement with willing Aboriginal partners,” etc, but did not, in nine paragraphs, touch on any obvious, recent conflicts and confrontations. Not even the Miq Maq crisis of Fall, 2012, regarding fracking in their territory and their accompanying rejection of their historic treaty with Great Britain; or the alliance of Nations throughout the west coast and watersheds who are preparing to blockade attempts to develop the Enbridge Gateway pipeline; or the various marches on mining companies’ AGMs in downtown Vancouver, demanding a halt to new projects and action on the Mt. Polley mine tailings spill into the Fraser watershed.

The state delegation did not respond to the question about “growing tensions.”

Over-representation of Aboriginal children in Child Welfare system

“Lastly, on the Child welfare front,” said Frank Wheldon, perhaps unconsciously slipping back into the tactical language believed to be used most often in his offices within Canada’s Department of Aboriginal Affairs, “there is a shift to move to a preventative approach. It may be too early to establish whether and what magnitude the impact might have… but signs are positive it may yield fewer numbers of Aboriginal children in the child welfare system.” The state representative did not say what those signs were, nor have there been any announcements in Canada pertaining to such a shift, or talk of a consultation process to direct that shift. The most recent and high-profile moment in Canada with regard to Aboriginal child welfare was the highly adversarial case at the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal between the state and the First Nations Caring Society, over the matter of severe under-funding to Aboriginal child welfare agencies.

The state has been asked about programs or monitoring offices which might keep in touch with young people who had been involved in the Child welfare system. The Committee was informed that no such monitoring and feedback program exists at the federal level. Although there are several community and academic research reports on this subject they were not mentioned, but according to Wheldon it would be too “complex” to attempt a follow-up program on a Canada-wide level, given the multiple jurisdictions involved. He said that there are “multiple provincial-level studies” being conducted.

Ms. Waterval had asked about the “alarming” number of Aboriginal children in state care, and the statistical likelihood of an Aboriginal child to enter that system. Wheldon said this too was “complex,” and “I would offer assurances that cases are seen on a case by case basis and decisions based on the best judgment of the people involved. Any differences that might exist there are still outstanding questions as to the full range of circumstances affecting that.”

Aboriginal languages

“According to a recent UNESCO report, of 87 Indigenous languages in Canada, 64 are definitely, severely or critically endangered. We are concerned about these alarming statistics and the state of Aboriginal languages in Canada. Canada’s written response noted the Aboriginal Languages Initiative, but made no mention of what contribution is made by the ALI and its achievements; please explain.

“We note the state has not moved forward on implementing the results of its Task Force on Aboriginal Languages and Cultures, 2005, and has not followed up since the “stakeholders” could not agree on a method of implementation of the recommendations. Please explain this lack of agreement.”

Martha Labarge, Director General of Canadian Heritage, replied for Canada. She read from a recent press release summarizing the purpose and objectives of the ALI, but did not answer the question concerning the lack of agreement by the 87 different language speaking peoples, nor did she clarify that Canada had imposed the condition of a single, agreed implementation strategy on those 87 peoples, or it would not fund implementation of the Task Force recommendations at all. Not surprisingly the 87 peoples, ranging from east coast to west coast, across the Great Plains and up into circumpolar regions, could not come up with a single implementation strategy that would suit all their needs. The Task Force report sits on a shelf. The federally conceived ALI has $5million annually, and apparently the expected results of the ALI program include: “Aboriginal people have access to community-based projects and activities that support the preservation and revitalization of Aboriginal languages and cultures; Aboriginal communities are assisted in their efforts to enhance languages and cultures; and Aboriginal languages and cultures are preserved and enhanced as living cultures.”

The ALI and its $5million annually is the sole federal funding source for language revitalization in Canada.

Some Indigenous observers were concerned when the Indian Residential Schools Survivors Settlement Agreement compensated people, through the “Common Experience Payment,” for “loss of language, culture and family life.” They seem to have accurately predicted the end of federal funding for language revitalization. Even the Board of the BC First Peoples’ Heritage, Language and Culture Council is getting advice from its Board of Directors to accept financial support from such unlikely places as Enbridge, since government sources are evaporating.

In a Note to Canada concerning Laurie Wright’s opening remarks about Canada, the Indigenous World Association observed, “We could not help but notice in your opening remarks to the Human Rights Committee that Canada had two official languages, English and French, and about 200 ethnic languages. We were very surprised at this. We didn’t think Canada had so many ethnic languages so we started to list them: Italian, German, Dutch, Russian, Welsh, Spanish, Portuguese, Greek, Slovakian, Latvian, Estonian, Lithuanian, Irish, Turkish, Hebrew, Arabic, Persian, Polish, Hindi, Bengali, Punjabi, Tamil, Burmese, Vietnamese, Cambodian, Mandarin, Japanese, Filipino and Swahili. These are all that we could list. We would like to see the list of 200 that you have.

We were very disappointed that you did not mention Indigenous languages to the Human Rights Committee. I am sure they would like to know that Canada has not wiped out all the Indigenous languages in Canada. After all, the Truth and Reconciliation Report of June, 2015, states that the purpose of the residential schools was to “through a process of assimilation, cause Aboriginal peoples to cease to exist as distinct legal, social, cultural, religious, and racial entities in Canada.”

If we can be of assistance, here are some Indigenous languages that you should know are still being used: Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca, Tuscarora, Cree, Micmac, Algonquin, Ojibway, Innu, Inuit, Dakota, Blackfoot, Dene, Haida, and many more.

We are very insulted… since you said that you take reporting to the Committee very seriously we have to conclude that your omission of Indigenous languages was deliberate.”

Canada’s choice to define Indigenous languages as ethnic languages is consistent with the condescending tone the written report takes in regard to Indigenous Peoples. Ethnic minorities do not have rights to self-determination which are connected to a land base: Indigenous Peoples do.

TRC

Margo Waterval followed up with questions about the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which Canada mentioned in its June 15, 2015 response to the LOI: “Canada continues to make progress on all aspects of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement. This includes financial compensation and the establishment of a Truth and Reconciliation Commission.” These efforts build upon the Prime Minister’s historic apology in June 2008, on behalf of the Government of Canada, to former students, their families, and communities for the abuse experienced by many who attended…”.

Waterval asked, “How many children died? Those who survived were estranged from their language and culture. Has the Commission completed its report? And what is the follow up? Is the government intending to accept and implement the recommendations in the report?”

Wheldon replied for the state delegation, “There was a report submitted in June. It’s not the full report, that is expected sometime by the end of the year. The initial report is something governments, not only the federal government, are studying carefully. There are multiple and far-reaching recommendations in the Call for Action. This is a process which will take some time to develop a government position on, and one which will require careful study once the final report is released.”

The reluctance to respond to the TRC report was also notable throughout Canadian media. The Minister’s office turned down a CBC interview; there was no media statement; and politicians were curiously reluctant to step into the news media’s quote-seeking searchlights. To date the government has made no statement to even formally accept or acjnowledge the report.

Education

Mr. Wasaba questioned the state’s written claim that education and training for Aboriginal people was achieving results; he asked for concrete examples. The state delegation did not provide any, but Wheldon said:

Mr. Wasaba also noted that the plan for First Nations Control of First Nations Education was also off track beause of lack of First Nation support. He asked, “why does this Act (FNEA) not have the support of the First Nation Chiefs? Does the government plan to change the Act?”

Frank Wheldon replied, among a long list of very quickly-spoken rote answers, “It’s difficult to say at this stage why the Act did not pass.” Mr Wheldon could have at least referred the Committee to dozens of news articles quoting leaders in education and elected Indigenous leaders as to exactly why the strictures, lack of funds, concessions, release of fiduciary obligations, and side-agreements contained in the First Nations Education Act caused it to lose all support and even caused the resignation of the AFN National Chief who publicly supported it, but he did not. “The act is in abeyance now, suspended actually, but it’s not off the table completely. There are a number of aspects of the Act which government is willing to advance with willing partners. There are communities willing to work on elements of the education Act, regarding infrastructure and building, which can be inserted into other Acts to continue support for Aboriginal education initiatives. Still, on many of the Act’s priorities there are individual communities and groups if communities and First Nations organizations willing to work to reform the education system on reserves.” Wheldon did not name any of them.

Other instances of no reply.

Any developments on the protection of Indigenous Peoples’ intellectual property?

In many cases, such as with the above question, the state did not reply. In some cases the delegates simply repeated the same press-release quality text which gave rise to the question for clarification or specific examples in the first place. They did not run out of time, however. The Chair had plenty of time to fill as the session expired on Wednesday at 1pm after two three-hour sessions beginning Tuesday afternoon.

The Committee asked the Canadian delegation whether the national First Nations organization, AFN, had been involved in the production of the state response to the Committee. It is rumored it was not, but Canada did not answer.

Concerning the land rights of Indigenous Peoples, one Committee member asked: “what steps have been taken and has there been a policy change since the Supreme Court of Canada ruling on the Tsilhqot’in land rights?” No one from the Canadian delegation answered that.

Although Canada fleshed out its response to number 19 in the List of Issues by noting a lot of program funding for such ventures as various self-government programs and First Nations delegated health authorities, they did not reply to this question: “Are self-governing agencies of this kind provided with sufficient resources to carry out these services?” The answer to that question is actually “no.”

In Summary

A 17 year old Líl’wat’s observation of Canada’s statements during the CCPR meeting:

“You know you’re in trouble when your entire race is lumped in a category with handicapped people, the elderly, offenders and pregnant women.”

The Canadian delegation:

Led by: Laurie Wright, Assistant Deputy Minister for the Public Law Sector at the Department of Justice

Paul MacKinnon, Assistant Deputy Minister | Public Safety

Martha Labarge, Director General at Canadian Heritage

Bruce Scoffield, Minister Counsellor at Permanent Mission of Canada to the United Nations

“Jessica”

And Lily Paul Nieuwe,

Apparently representing in sum the: Department of Justice, Portfolio Affairs and Communication, Aboriginal and External Affairs, Strategic Management and Human Rights, Trade Commissioner Services and Operations, International and Intergovernmental Relations, Human Rights Law Section, Ministry of International Relations and Francophony of the Government of Quebec, and the Permanent Mission of Canada to the United Nations Office at Geneva.

* A question which was asked in the List of Issues but not answered by Canada’s written reply.

** A question which was repeated during the two-day public meeting.

[i] This spelling is an approximation based on the sound of the speaker’s name being announced by the head of the Canadian delegation, Laurie Wright. No searches of any spellings of this name which sound close produce any results in searches of Aboriginal Affairs websites from Canada.

[ii] The Assembly of First Nations is populated by the elected Chief of every Indian Band (or First Nation). However, it is a rare thing for elected Chiefs to bring home AFN business and hold community referendums on those issues and then return to AFN to represent their community’s interests on the matter at hand. The Recently failed First Nations Education Act, which the national Chief of the AFN participated in developing, is one example of the disconnect. Another example is the “Crown First Nations Gathering” in January of 2015, which produced a “to-do” list that left grassroots and urban aboriginal people amazed at the gap between themselves and the “willing partner” attitude displayed by their Chiefs towards the state government.