Part 1 – What do you mean, “reconciliation”?

September 30th is the “National Day for Truth and Reconciliation.”

There aren’t enough calendar days in a year to mark the trespasses, and ensuing debts to humanity, amassed by the colonial Canadian project. For instance, when is “Compensation Day”? When is “Land Back Day”? And, “White women got Indian Status by Marriage, and Native women lost it.” Lest we forget.

For now, let’s talk about “Reconciliation.” “Truth” was abandoned fairly early on in the proceedings.

Traditionally, “reconciliation” of legal issues refers to the fulfillment of actions that will be taken to restore the peace and justice, as in a judicially prescribed schedule of reparations following a court decision.

We just don’t have the court decision, unless you count the Indian Residential Schools Survivors Settlement Agreement and the report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. But you can’t count those, because they were both mandated, conducted, written, and decided by one of the parties to the dispute. The dispute is between Canada and every Indigenous nation, so the judge can’t be one of those parties.

Imagine if somebody wrongs someone else and then conducts the inquiry as to what should be done about it. That is pretty much what Canadian “reconciliation” is.

If a judge – a court – is impartial to the outcome of a question, then they can have jurisdiction. But Canadian courts are not impartial to the outcome of the Indian land question, because those Canadian judges and all their friends and family and everyone who works for those courts have an interest in Canada winning the competition, so they lose jurisdiction because they’re not impartial.

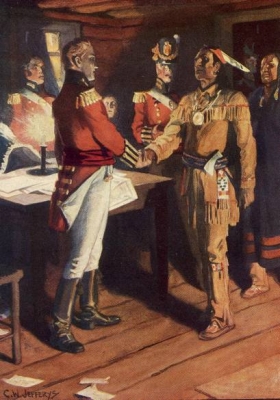

Most unbiased observers would also notice that Canada has no treaties with Indigenous Peoples that include subjugation of Indigenous Peoples to arbitrary and unilateral Canadian decisions and values, to the total exclusion of the native right of law and jurisdiction.

If there were any application of “truth” to these affairs, “reconciliation” would involve an independent, impartial tribunal. And it would be well-defined.

The Prime Minister has formally stated a national pursuit of something that has no definition. Cities and provinces use the word “reconciliation” to mean anything from “business as usual, but with a big native art motif,” to “we said reconciliation, what more do you want?”

“Reconciliation” lacks all definition.

What it is and what it ain’t: what we know for sure about reconciliation

We definitely don’t know what it is. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Canada, itself did not offer a definition and did not have one written into its mandate. In fact, the TRC’s Call to Action #65 recommends the government work with policy and educational institutes to flesh out an understanding of reconciliation.

We do know a lot about what Canadian reconciliation isn’t. It’s not a legally defined process. It’s not binding. It has not been, and will not be, overseen by an independent, impartial, third party. It clearly does not mean that the RCMP will stop terrorizing and arresting land defenders when “negotiations” reach an impasse over cutting a 150km road through pristine forest and putting an oil pipeline there. And courts won’t stop finding them guilty and jailing them, as they did to Gidimt’en defenders in 2022.

We know how the police and RCMP think about reconciliation. The cops sent to stand off against the roadblock were heavily armed, and they arrested people with guns drawn. They referred to their guns as “reconciliation sticks.” We’ll talk about the meaning of that in Part 4 – Enforcement of Reconciliation.

Canadian “reconciliation” is so different than the reconciliation articulated by an Indigenous “Reconciliation Manifesto,” written by the late Arthur Manuel in 2017, that we very quickly apprehend the double entendre of the term. Manuel made it clear that, for Indigenous nations, there is a clearly marked reality to reconciliation – if there is any point to it at all:

“We will know that Canada is fully decolonized when Indigenous Peoples are exercising our inherent political and legal powers in our own territories up to the standard recognized by the United Nations, when your government has instituted sweeping policy reform based on Indigenous rights standards and when our future generations can live in sustainable ways on an Indigenous designed and driven economy.”

There are more than two distinct uses for the word reconciliation. One use refers to the restoration of peace, as described by Manuel – in very similar terms to thousands of native leaders since 1871 – and it refers to human relations. The other use of “reconciliation” is mainly applied to non-human imbalances: while building a house, you can literally reconcile a floor joist to match the door frame. Or you can achieve reconciliation in the budget, if you make some nips and tucks.

It is these latter, mechanical definitions which Chief Justice Antonio Lamer first used, in 1996, when he wrote that Section 35 of the Constitution is a tool with which to ensure the,

“…reconciliation of the prior existence of aboriginal societies with the sovereignty of the crown,”

Chief Justice Lamer, head of the Supreme Court of Canada from 1990 to 2000: right after Sparrow, through Delgamuukw, was talking about bringing round the as-yet unconvinced and unceded nations into Canada – whittling away the incompatible worldviews, traditions, and legal rights to the soil that don’t fit the colony’s vision for itself. He wants to reconcile those ill-fitting, autonomous Indigenous Nations, into Canadian structures. He was hardly the first.

Lamer was not interested in the way that Section 35 confirms the “existing Aboriginal and treaty rights” described in the Royal Proclamation 1763 and the British North America Act, with its Section 109. But the last time Canada tried to get rid of those, in 1976, when it made itself a new constitution that deleted those parts and any reference whatsoever to His Majesty’s independent Allies, there was an intercontinental movement called the “Constitution Express” mobilized by the Indigenous Peoples to remind their one-time Ally, Britain, about them. The British House of Lords was reminded, and forbade Canada to cut its legal roots. Hence Section 35 (1), affirming them in the Constitution Act, 1982.

So Justice Lamer said that section 35 is a “mechanism” to achieve “reconciliation.”

What he actually meant, following his wordplay through the dozens of illustrations he elaborated in the van der Peet ruling, was extinguishment of Aboriginal rights by negotiation. That was his prescription for reconciling the “pre-existing” societies with Canada, and, in the meantime, defining Aboriginal rights under the Constitution – one sockeye salmon at a time.

(Note: In Lamer’s ruling, Ms. van der Peet was affirmed in her sale of ten sockeye under an Aboriginal Food, Social, and Ceremonial fishing license. She sold them to a friend for $10 a piece.)

The only negotiations available to Indigenous Peoples are defined unilaterally by Canada, and they end in relinquishment of rights and claims in exchange for a little money and a little less land (very little) in fee simple title. This result is widely referred to as extinguishment, because… it eliminates the existing rights.

We’ll look at that more closely in Part 2, Reconciliation: Theft by Chief Justice.

Meantime, Canadians need to realize that the ‘spirit of reconciliation’ issuing from the upper echelons of their state is a mean one. That’s undoubtedly why the leaders of the society skirt the issue of defining it, and hide behind whatever hopeful face that sincere people want to project on it, and carry right on with business as usual.

The one term has so many uses

The term “reconciliation” has been wash-boarded across the media, which rolls it into play indiscriminately, no matter whether its usage is coming from the judicial, legislative, or executive branches of state; or from individual experiences; or from former Indian Residential School students’ families, who reasonably hope it means change. Unfortunately, it has two more working meanings that are really freezing cold in the shadow of Canadian denial.

Reconciliation also means “being resigned to something undesirable, or the process of reaching that state; acceptance.” And, finally, the word is used by Roman Catholics specifically to refer to penance, where perpetrators are forgiven by their god.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission explained, in one of only a handful of attempts to positively define the term they were named for, that in the case of Indian Residential Schools (IRS),

“…reconciliation is similar to dealing with a situation of family violence.”

“Reconciliation is an ongoing individual and collective process, and will require commitment from all those affected including First Nations, Inuit and Metis former Indian Residential School students, their families, communities, religious entities, former school employees, government and the people of Canada. Reconciliation may occur between any of those groups.”

This seems like a categorically inadequate and vague suggestion. But that is the strength of the concept of reconciliation, and, as such, it serves the exact purpose which Justice Antonio Lamer invented it for: to turn real, well-defined, constitutional rights – section 35 (1) – into a ‘platform for negotiation.’

It’s now a quarter century since the government of Canada’s “Statement on reconciliation,” was read out, in ceremony, by Minister of Indian Affairs Jane Stewart. It came two years after the Supreme Court of Canada’s new invention.

She was announcing Canada’s response to the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, RCAP 1992-96, and their 4,000 page report. The government’s “Gathering Strength” action plan, 1998, was focused on issues raised by the Commission like early childhood education for Aboriginal communities; housing, water and sewer systems; welfare reform; major injections to the land claims negotiation process, to produce final agreements; and a $350m healing fund – the Aboriginal Healing Foundation.

Keep in mind that the RCAP was forced by an armed stand-off at Oka, where control of the land was at issue – not preschools; not increased welfare relief; not affirmative action schemes; not expediting land claims, but jurisdiction over the land.

Minister Stewart famously announced that the government of Canada “regrets” its role in the Indian Residential School system. The government demonstrably regrets nothing: Canadian money is still a solid eighty-cents-on-the-dollar coming directly out of the land. Indian Residential School enforced every child’s attendance for fifty years, and was one of the most effective strategies to destroy Indigenous groups, right along with smallpox, wiping out the buffalo, and the Indian Act. It’s one of the main reasons Canada gained access to their lands.

By the time Canada stated its “regrets,” every church involved had already given public apologies. But the Indigenous people had to wait until 2008 – after the ratification of the IRS Settlement Agreement – before Canada apologized.

Why is it that Indigenous Peoples, or individuals, have to sign something in order for Canada or provinces to apologize, or recognize, or “reconcile”? We’ll look at that more closely in “Part 4 – Enforcement of Reconciliation,” where the business-end of Canadian reconciliation is mutual recognition.

Canada has been importing and exporting its Indigenous title workarounds for decades. They echo back, and British colonies support each other. Hey, the first treaties in British Columbia were signed blank by Snuneymuxw Chiefs with “X”, and sent to New Zealand for the most current Imperial text. Australia cottoned on to ‘reconciliation’ by the year 1991. They made up a Bill,

“To establish a Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation (the Council) to promote a process of

reconciliation between Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders and the wider Australian community.”

The Bill passed. Today, they use it in a very similar way to Canadian “reconciliation,” with “Reconciliation Australia” providing online portals for Australian businesses to post slides about mounting native art in the lobby, or Aboriginal customers – but not about justice, land back, compensation, reparation, or restitution. On October 14 this year, Australians voted overwhelmingly against giving Aborigines a voice to their Parliament.

There is something called “Global Affairs Canada’s action plan for reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples 2021-25.” They mean Indigenous Peoples all around the world. Presumably they want to make Indigenous Peoples everywhere conform to their interests, as per “reconciliation Def. #2 – to make compliant with” like they do here.

GAC says, “Global Affairs Canada is committed to applying a reconciliation lens across its diplomacy and advocacy, trade and investment, security, international assistance, and consular and management affairs.” This will be informed by the TRC’s Calls to Action, and the Report on Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women. Suffice to say neither of those Canadian commissions’ reports deal with land title, self-determination, jurisdiction, or reparation either.

Canada and British Columbia have both unilaterally passed legislation concerning the UN’s Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. The Canadian UN DRIP Act is a fretful talk-and-log strategy which does nothing to improve Indigenous rights, but legislates that Indigenous Rights should be observed, whenever Canadians and the Indigenous agree on how that should be done. Canada ratified the International Declaration almost ten years after it first passed the UN General Assembly – but not before getting a few sub-standard “reconciliation” issues entrenched first in the 2015 TRC report. We look at that in Part 4 – Enforcement of Reconciliation.

Although they do not act like it, “…all Canadians are treaty people, bearing the responsibilities of Crown commitments and enjoying the rights and benefits of being Canadian.” That is how George Erasmus put it, when he was longtime-President of the Aboriginal Healing Foundation, in “Cultivating Canada; Reconciliation through the lens of cultural diversity.” It’s a 2011 Aboriginal Healing Foundation publication.1

The treaty people aren’t acting properly: they pass legislation and think it should affect the self-determining people.

The self-determination of Peoples means that which is arrived at, by Indigenous Peoples, freely determining their political status, on their own territories. And not by any means to be coerced out of their natural wealth. It’s in the International Bill of Rights, 1969, which is two Conventions: one for the rights of Peoples to Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (CESCR), and one for Civil and Political Rights (CCPR). Canada hasn’t come around to recognizing that Indigenous Peoples are “Peoples” within the meaning of such international treaties and statutes.

The Standing Committee on Indigenous and Northern Affairs has, this year, embarked on a study of Restitution of Land to Indigenous Communities. A similar investigation was called for by the former Prime Minister, John Diefenbaker, fifty years ago. At that time, for the first time, three Supreme Court of Canada judges ruled that Aboriginal title exists in Canada and it hasn’t been, couldn’t have been, shifted by any unilateral action of the state.

Will restitution be made to self-determining Peoples and nations? Or to treaty First Nations which have traded their sovereignty (in exhaustion and duress) and unextinguished land claims for a few acres and municipal status? “Reconciliation” doesn’t say, it doesn’t offer guidelines consistent with international law and convention; it says wait and see.

We’ll look a lot more closely at that in Part 3 – Reconciliation as Subterfuge.

In 2004, the feds lost track of a secret policy document, it was leaked, and it explained all about how “the concept of reconciliation” would “secure investment, stabilize certainty,” and – always last in line – “promote socioeconomic development in Aboriginal communities.” The government has told us what it wants out of this reconciliation project, and it has a lot more to do with starving-and-coercing Indigenous leaders into major releases.

How should Canadians understand their role, or their government, and the urgent task of averting genocide before them, when their elected leaders are clearly using a term of utmost importance in a duplicitous way?

For too long Canadians have been slaves to greed and desperation, partly informed, no doubt, by many of their own flights from genocide and colonization. The Sto:lo word for the white people, when they arrived in the Fraser Valley, translates as “the hungry ones.” But not just hungry; “insatiably hungry and never satisfied.”

When Canadians talk about “reconciliation,” they should be specific:

“I mean hurrying up land claims so we have certainty for investment,” as per federal policy.

“I mean enacting Canadian legislation to improve the way native families interact with social workers in the Ministry of Children and Families,” as per the TRC calls to action.

“I mean forcing impoverished communities to relinquish their rights, under duress, in the only negotiated land claim settlements Canada will offer,” as per the Supreme Court of Canada.

“I mean redecorating the academy, you know, and making a list of Indigenous gift shops so professors can buy suitable thankyou presents for guest speakers,” as per university ‘decolonization handbooks.’

“I mean hurrying up self-government agreements with the First Nations, following Canada’s “Inherent Rights Policy,” and as augmented by the First Nations Governance Act, the First Nations Fiscal Responsibility Act, and the First Nations Land Management Act,” as per federal policy. “You know, to reconcile their pre-existence with the sovereignty of the crown.”

Or maybe they mean something sincere, but on a personal level:

“I mean – holy cow – I have sat up all night and all day all week and just tried to come to grips with the realization that everything that happened to us in Ireland, the British took our worst monsters – graduated up through the Christian Brothers industrial schools, and brought them here to do the same to these people,” as per the individual journey.

And even,

“I just heard about “Namwayut” and I’m learning to be reminded that: “we are one in the universe, and we are one with the universe,” as per readers of Chief Robert Joseph’s book, “Namwayut ~ A Pathway to Reconciliation.”

But …

If Canadians want to talk about unqualified Land Back; if they mean RCMP out; if they mean recognition of and restitution of authentic governments; justice for crimes of genocide; and if they mean reparations and compensation, they are not talking about the reconciliation promoted by Canadian institutions and the legal and executive branches.

The “True Reconciliation” sticks are rattled to drum out and silence unassimilated, autonomous people who want to determine their own future: who know their rights come from their Creator and ancestors – not from Canada.

Peace and justice are the more appropriate objectives.

Tsawwassen, Musqueam, Tsleil Waututh, and Squamish Peoples, among others from Sto:lo to Tagish, are internationally protected people. They are protected from us – Canadians – and you can see why.

Let’s reconcile, and I mean here, “accept the very uncomfortable fact,” with that: Canada does not have the treaties – it does not have the consent or agreement – with Indigenous land title holders.

Currently, “reconciliation” is a coercive process, enforcing colonial control and interference, and denying the Peoples’ rights.

Thank you very much for reading. Takem i nsnukw’nukw’a.

Check in tomorrow for Part 2 of No more “Reconciliation Sticks” – Theft by Chief Justice.