Tags

aboriginal title, Canada, Comprehensive Claims Policy, Cowichan, history, indigenous, Indigenous Peoples, Land claims, news, politics, Richmond, Tl'uqtinus

Concerning, how does a declaration of Aboriginal title affect the non-Native people now living in the ancestral village of Tl’uqtinus, where Cowichan title has been judicially declared?

Tl’uqtinus – tah-look-TEEN-oosh (*an approximate anglicism) – is a 1,846-acre area which overlaps the City of Richmond, lying along the Fraser River.

On August 7 of this year, the Supreme Court of British Columbia gave a ruling on the Cowichan Tribes’ claim to Aboriginal title to that area. This case is now the longest-ever Aboriginal title case, running over 500 days in trial.

The judge made a declaration of Aboriginal title to most of the area, which is a seasonal Cowichan fishing village. Madam Justice Young decided that, “The Crown grants of fee simple interest in the Cowichan Title Lands, and the Crown vesting of the soil and freehold interest in the Richmond Tl’uqtinus Lands (Highways) in the Cowichan Title Lands, unjustifiably infringe the Cowichan Nation Aboriginal title to these lands.” She concluded that most of the current land titles in the area are “defective.”

Since then, panic has gripped the province of British Columbia – just as it has after every successful Aboriginal rights case since the first one in 1964. The Province of BC, Canada, and the City of Richmond are appealing the ruling instead of entering negotiations with the Cowichan Tribes.

The judge suspended the effect of her declaration for eighteen months, to provide time for transition, but all levels of settler government have made it clear they intend to fight cooperation with Cowichan interests and title every step of the way – as they have after every declaratory recognition of Aboriginal land rights since 1875.

The following analysis is based on an extensive survey of Aboriginal rights litigation arising west of the Rocky Mountains; an extensive survey of the circumstances leading up to such litigation and the clear public statements made by Indigenous plaintiffs, as well as the statements of claim; an extensive inventory of provincial behaviours since colonization; and a review of non-Native reaction to the Cowichan title case.

1. Aboriginal title is not the same as fee simple title

What Canada has all along been calling “Aboriginal title” – a sui generis and abnormal concept – are actually national titles, flowing from centuries and millennia of law and governance.

“Aboriginal title” is a colonial construct used by the crown to obscure Indigenous Peoples’ land rights and subject them to the discretion of the crown. The Cowichan, among others, have now outlived that construct. They, like the Tsilhqot’in just before them, have forced the court to recognize the practical aspect of Aboriginal title. The court, in Cowichan, has ordered that the government of British Columbia must negotiate a resolution to the title conflict. (See the Summary of Declarations below)

In case after case, for fifty years, crown courts have reduced the meaning of their own invention, “Aboriginal title lands,” to mean nothing more than the right to use and occupy “small spots,” or “postage stamp title” – around fishing rocks, hunting blinds, and “fenced village sites” – as if these were private holdings on crown land.

Settlers have been left not understanding what Indigenous Peoples’ land titles really are, while the courts have attempted to define them out of existence.

2. Co-existence of Aboriginal title and fee-simple ownership

Because what “Aboriginal title” actually refers to is those national titles, and the underlying title belonging to that Indigenous Nation or People, the underlying Indigenous land title co-exists with individual property ownership in almost exactly the same way that fee simple title holders relate to what they thought was underlying crown title.

There have always been individual land titles throughout Indigenous Nations. The nations are made up of Clan and House Lands, and titles which must be upheld in regular actions of governance and social obligation. Not unlike the taxes and bylaws of today’s settler regime.

Recently, many people have piped up to the tune that Aboriginal title, as a right to the land, cannot co-exist with fee-simple property ownership. This represents a level of ignorance that has moved into the hysterically incompetent. The same people who loudly make that statement are quite happily paying their taxes to BC and Canada, in full recognition of the idea that their fee-simple ownership co-exists with underlying crown title. They also fully expect to go along with crown appropriation schemes, maybe for a hydro right-of-way, or for a city works infrastructure project; to receive their non-negotiable compensation for that part of their property that was used; and to go on with their land-holding.

3. Displacement

Native plaintiffs have never set out to displace individual property owners in title litigation.

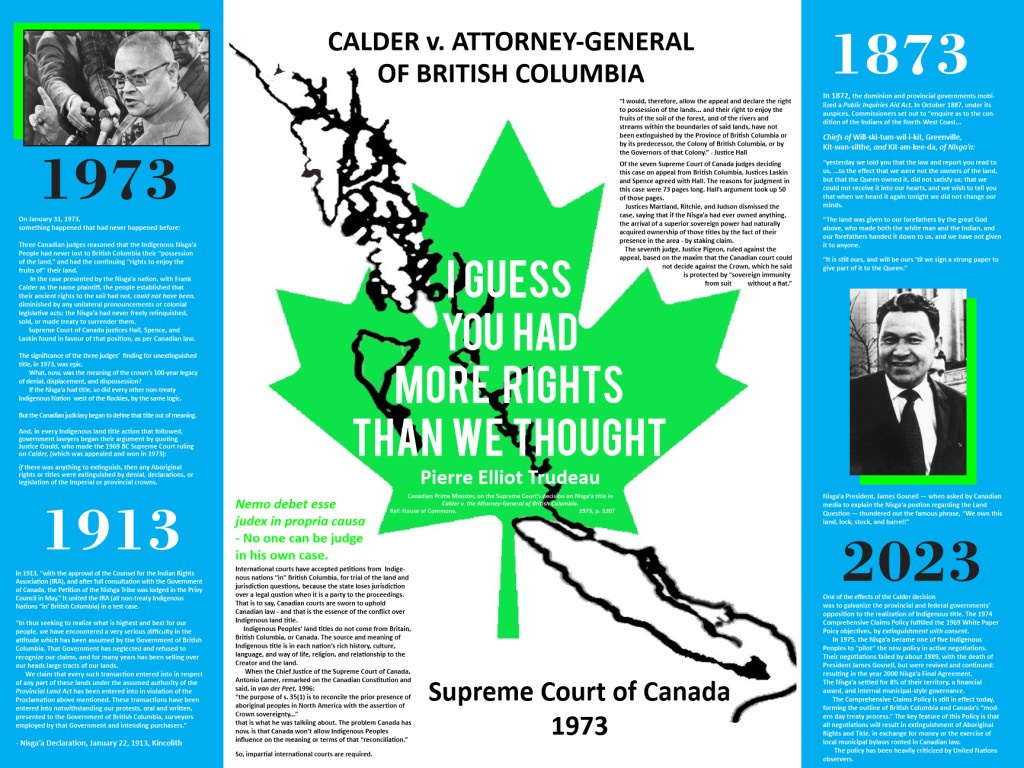

Ever since the Nisga’a title case in 1973, every court action has specifically excluded claims to ownership of the fee-simple title of individual homes and properties. This includes the Cowichan claim.

Indigenous Peoples demand recognition of their underlying title.

In this way, Native communities have protected settlers from their own colonial government’s theft, bad faith and lies.

In many instances, First Nations have attempted to negotiate with the crown for the buy-out and return of lands which the crown sold to settlers or developers. These negotiations were not litigation.

4. Cowichan fishing rights

Tl’uqtinus is a fishing village. A thousand Cowichan people would go there – well into the 20th century – to harvest salmon returning up the Fraser River. They navigated the Salish Sea from their main territory on “Vancouver Island” with enough people and provisions to live for the season. Their big houses and a few residents stayed year-round on the lower Fraser at Tl’uqtinus.

As of this decision, the Cowichan are one of only five Indigenous Peoples west of the Rocky Mountains to have a judicial declaration of their right to fish for food. This fact is provided to assist non-Native readers understand the extent of colonial repression of economic, social and cultural rights which they must now correct along with land title.

The other peoples with recognized Aboriginal fishing rights – not just the very recent legislative “accommodation” of Aboriginal rights without explicit recognition and protection, or the modern-day treaty provisions by agreement – are the Musqueam (Sparrow 1990); the Heiltsuk (Gladstone, 1996); the Saik’uz and Stellat’en (Thomas, 2024); the Nuu-chah-nulth (Nuu-chah-nulth, 2021); and the Douglas Treaty nations (1850-54).

5. “Aboriginal title” is a politically-motivated colonial construct

What Madame Justice Young did not point out in her reasons for judgement in this case, is that “Aboriginal rights” is an invention of Imperial and Colonial British courts, along with Britain’s Privy Council and Foreign Secretary, to set aside the land rights of Original Inhabitants invaded and annexed by the British Empire.

There is currently no legal reality to Aboriginal title in Canada: it remains undefined as sui generis: Aboriginal title land can’t be (won’t be) registered by provincial Land Titles offices; the government says it has no market value because it can only be “surrendered” to the crown by agreement.

This archaic and internationally repugnant discrimination has been the subject of many UN treaty bodies’ observations concerning the situation of Indigenous Peoples in Canada. It is also the reason that the judge in Cowichan can do nothing more than urge the government to negotiate the surrender of the declared Aboriginal title lands, in exchange for rights by agreement. That is Canada’s policy. There is no mechanism to mobilize or actuate Aboriginal title land.

One participant at the Richmond City Hall meeting described the situation to a reporter, “If this brick in the wall comes loose, the whole thing’s going to come down.” That is the perspective of a non-Native person who knows absolutely nothing about the Cowichan Tribes.

A few more observations

The Richmond meeting, October 28

When Richmond’s Mayor Brodie called a little meeting for last Tuesday night, which was, in his words, “intended to influence the court,” the Cowichan representatives naturally did not attend. The Indigenous experience in the court of public opinion has been dismal: the 2002 BC Treaty Referendum; the 1992 Charlottetown Accord; etc.

Unfortunately, while the province of BC has wasted no time appealing the decision in toto, and loudly repeated its historical refusal to recognize Indigenous Peoples’ equality to other Peoples, the Cowichan Tribes are not going to make a lot of public statements to reassure the Richmond citizens (however much they undoubtedly would like to), when those political statements could then be interpreted by the appeal court to undermine their legal position.

Settlers might be interested to take their own initiative, to learn about the Cowichan Tribes, and to see if their racism survives education.

Life on Aboriginal title lands

Newcomers to BC have lived with the practical reality of national Indigenous titles underlying their fee-simple holdings since at least 1985, in the Sechelt Self-Government Agreement. Well, Indigenous titles have laid under the settler land tenure system all this time; the title-holders have just been very patient in waiting for the newcomers to gain consciousness in relation to their surroundings.

More recently, the 2014 Supreme Court of Canada Tsilhqot’in decision – for the very first time – made a declaration of Aboriginal title to marked, mapped areas on the ground. Those areas also include lands which were sold to settlers by the crown that didn’t own them. No one has been evicted (although one guy who dredged a salmon spawning stream to improve irrigation will surely be reprimanded). In the Haida Rising Tides Agreement, 2024, settlers seem to have survived provincial recognition of Haida title to Haida Gwaii. In 2002 the Haida filed a statement of claim to their entire territory with the BC Supreme Court, but, such was its indefatigable certainty, BC was compelled to provide a series of stop-gap agreements since then, Rising Tides being the most recent, which have stopped that litigation from proceeding.

Other jurisdictions where non-Native property owners have interests which are actively recognized, respected, and served by Indigenous Nations are in Tsawwassen, since the 2007 treaty; in Powell River, since the 2007 Sliammon treaty; in Nisga’a, since the 2000 Final Agreement; in Westbank, where people bought 99-year lease holds following the Westbank Self Government agreement; and in Kamloops, following an adjustment of the Indian Act to mobilize housing development on-reserve in the urban center.

The difference here is that “Aboriginal title” is an “undefined Aboriginal right.” Extinguishing undefined Aboriginal rights is the lead purpose of government Agreements with First Nations today, whether it be under the BC Treaty Commission, or in the new Sectoral Agreement Strategy where the same suite of treaty rights are determined one at a time by stand-alone deals like the “Education Jurisdiction Agreements,” or, for Children and Families, under the federal enabling legislation in Bill C-92; or, for Lands, under the First Nations Lands Management Act; or in Health, Resources, or Taxation authorities.

The written decision in Cowichan

The decision in Cowichan Tribes v. Canada makes excellent reading. The judge has included many selections from the Quw’utsun Elders’ testimony at trial. Their way of life is truly awe inspiring, and the many descriptions of Quw’utsun ways of governance are enlightening. Justice Young has also included much of the pivotal evidence concerning the history of Tl’uqtinus, such as descriptions of the village provided by Captains of the British Navy, maps of the area made by colonists and showing the village site, et cetera.

At the same time, Young has included all the parties’ positions on the issue, and the real extent of institutionalized settler denial and racism is there for all the world to read, in the Province, Canada’s, and the City of Richmond’s outrageous statements.

Title Insurance

The State of Hawaii has adapted to a similar stolen-and-settled land situation by enabling “Title Insurance.” In the same way that homeowners buy fire or flood insurance, they also buy title insurance specific to mitigating the inevitable recognition of underlying Indigenous title to their property.

This development followed a successful Indigenous Hawaiian title case against the state in about 2004.

Pleading ignorance

Pleading ignorance is very rarely a reasonable explanation for illegal behaviour with ongoing harms. What plagues the people of Richmond today is not Aboriginal title, but racist denial and the courts’, politicians’, and media’s refusal to do anything more than insult the title holders.

The Supreme Court of Canada first swerved to avoid even hearing the title argument in 1965, in the Snuneymuxw hunting case, White and Bob. The courts have protected settler ignorance for as long as possible, but perhaps the Cowichan decision is a watershed moment – following many precipitous moments.

The Tla-o-quiaht won an injunction against logging Meares Island in 1985 on the basis of their Aboriginal rights. The Nisga’a started negotiating their land claim in 1976 on the basis of their 1973 Calder ruling. The BC Treaty Commission was formed in 1992 to settle land claims. By 1981, Native claims were being pursued by almost every Indigenous tribe “in” BC, under the Office of Native Claims Commission, 1974. Canada’s policy on Native Claims has been so unfair that few agreements have been reached, west of the Rockies.

No one can claim to be surprised that Indigenous Peoples have land rights.

Helpful quotes from previous rulings:

“The province has been violating Aboriginal title in an unconstitutional, and therefore illegal, fashion ever since it joined confederation”

- Justice Vickers, BC Supreme Court, Tsilhqot’in 2007

“Aboriginal title and rights have never been extinguished by any action taken by the province of British Columbia.”

- BC Court of Appeal, Delgamuukw, 2003

“The domestic remedy has been exhausted.”

- Inter-American Court of Human Rights, Washington DC, Hunquminum Treaty Group v. BC 2009 (Note – the Hunquminum Treaty Group is a Cowichan organization)

EXCERPTS from the decision in Cowichan

Cowichan Tribes v. Canada (Attorney General), BC Supreme Court, August 7, 2025

The Full Ruling:

From the Introduction to the case, by Justice Young:

• Between 1871–1914, Crown grants of fee simple interest were issued over the whole of the Claim Area, including the Cowichan Title Lands.

The first purchase of Cowichan Title Lands was made by Richard Moody who was the first Chief Commissioner of Lands and Works for the Colony of British Columbia and was tasked with ensuring that Indian reserves were created at sites of Indian settlements. Because occupied Indian settlements were appropriated, and could not be sold, most of the Crown grants in the Cowichan Title Lands were made without statutory authority.

• British Columbia was admitted into Canada on July 20, 1871 under the BC Terms of Union. The effect of Article 13 of the BC Terms of Union was to extend appropriation of Indian settlement lands post‑Confederation, limiting the Province’s ability to sell the land without first dealing with the Cowichan’s interest. As a result, the post-Confederation Crown grants in the Cowichan Title Lands were made without constitutional authority because they were made under legislation that was constitutionally limited by Article 13.

• The Crown grants of fee simple interest deprived the Cowichan of their village lands, severely impeded their ability to fish the south arm of the Fraser River, and are an unjustified infringement of their Aboriginal title. Subsequent dispositions of the Cowichan’s land, including BC’s vesting of Richmond with fee simple interests and the soil and freehold of highways, are also unjustified infringements. Additionally, some of Canada and the VFPA’s activities on the Cowichan Title Lands unjustifiably infringe the Cowichan’s Aboriginal title.

• The Province has no jurisdiction to extinguish Aboriginal title. The Crown grants of fee simple interest did not displace or extinguish the Cowichan’s Aboriginal title.

*emphasis added

Summary of the Cowichan Ruling, Justice Young

D. SUMMARY OF THE DECLARATIONS

[3724] In summary, I make the following declarations:

• The descendants of the Cowichan Nation, including the Cowichan Tribes, Stz’uminus, Penelakut and Halalt, have Aboriginal title to a portion of the Lands of Tl’uqtinus, the Cowichan Title Lands, within the meaning of s. 35(1) of the Constitution Act, 1982.

• The Crown grants of fee simple interest in the Cowichan Title Lands, and the Crown vesting of the soil and freehold interest in the Richmond Tl’uqtinus Lands (Highways) in the Cowichan Title Lands, unjustifiably infringe the Cowichan Nation Aboriginal title to these lands.

• Canada’s fee simple titles and interests in Lot 1 in Sections 27 and 22 (except those in the YVR Fuel Project lands), Lot 2 in Section 23, and Lot 9 in Sections 23 and 26, and Richmond’s fee simple titles and interests in Lot E in Sections 23 and 26 and Lot K in Section 27, are defective and invalid.

• With respect to the Cowichan Title Lands, Canada owes a duty to the descendants of the Cowichan Nation, including the Cowichan Tribes, Stz’uminus, Penelakut, and Halalt, to negotiate in good faith reconciliation of Canada’s fee simple interests in the YVR Fuel Project lands with Cowichan Aboriginal title, in a manner consistent with the honour of the Crown.

• With respect to the Cowichan Title Lands, British Columbia owes a duty to the descendants of the Cowichan Nation, including the Cowichan Tribes, Stz’uminus, Penelakut, and Halalt, to negotiate in good faith reconciliation of the Crown granted fee simple interests held by third parties and the Crown vesting of the soil and freehold interest to Richmond with Cowichan Aboriginal title, in a manner consistent with the honour of the Crown.

• The descendants of the Cowichan Nation, including the Cowichan Tribes, Stz’uminus, Penelakut and Halalt, have an Aboriginal right to fish the south (i.e., main) arm of the Fraser River for food purposes within the meaning of s. 35(1) of the Constitution Act, 1982.

[3725] Most of the Cowichan’s Aboriginal title lands at Tl’uqtinus were granted away over 150 years ago. Since that time, the Cowichan have pursued the return of their land, first through the JIRC process, causing Gilbert Sproat to write to the Lieutenant Governor in 1878: “The ancient fishing ground on the Lower Fraser of the Cowichan nation … has been sold and now belongs to a white non-resident. What can be done in such a matter?” Although it has taken a very long time, the Cowichan have now established their Aboriginal title to that land. These declarations will assist in restoring the Cowichan to their stl’ulnup at Tl’uqtinus and facilitating the revitalization of their historical practice of fishing for food on the Fraser River and teaching their children their traditional ways. Nevertheless, much remains to be resolved through negotiation and reconciliation between the Crown and the Cowichan.

[3726] Additionally, the determinations in this case will impact the historic relationships between the Cowichan, Musqueam and TFN, and relations moving forward. The fact is all the parties have continued interests, rights and obligations around the south arm of the Fraser River and limited resources need to be shared and preserved.

[3727] Much has been written about reconciliation. The principles of reconciliation defined by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada include the process of healing relationships that required public truth sharing, apology and commemoration that acknowledges and redresses past harms. Litigation is the antithesis of a healing environment as the adversarial system pits parties, and sometimes kin, against one another. Yet at times it is necessary in order to resolve impasses such as those that arose here, halting negotiations. Now that this multi‑year journey has concluded, it is my sincere hope that the parties have the answers they need to return to negotiations and reconcile the outstanding issues.

[3728] The plaintiffs have been successful in this trial and are entitled to their costs. If the parties cannot agree on the scale or apportionment of costs they may apply to the Court for a hearing on the matter.

“B. M. Young, J.”

The Honourable Madam Justice Young