A Timeline of Events: Pacific and Inland Salmon Fisheries west of the Rocky Mountains

This Timeline concerns interaction between Indigenous Peoples and the colonial governments, as well as documentation of the decimation and recovery of salt- and fresh-water fisheries which sustained human civilization in this area since time immemorial.

This collection is currently being uploaded at regular intervals.

Mainstream media content is provided although often inadequate when describing Indigenous matters.

Birkenhead sockeye.

before 185

“Salmon is the lifeblood of the people.”

Pre-1850: Salmon and seafood were the primary and secondary sources of food for most people along the coast and, and salmon for most people in the interior of BC, as well as being a popular form of currency inland. Dried salmon retained its food value for years.

People would catch and preserve at least two years’ supply when runs were strong, as the Fraser sockeye follows a four-year cycle of abundance. Chinook salmon were the most used fish of the interior tribes.

Fishing was done along rivers by weir, gaff, traps and dip nets. Weir fishing has been described as a live, selective fishery, where salmon are blocked below a fence in the river. Fishermen then select males, jacks, or other fish less suitable for reproduction.

The Fraser sockeye population is thought to have been 100 million fish every fourth year on the dominant cycle line, and 30 million in the low years.

Tribes of the lower Fraser relied very much on sturgeon and Eulachon. Eulachon were so abundant, they were fished out of the Fraser, in the strength of their migration to the Chilliwack River, with large rakes – a person could stand in the shallows and sweep the fish up onto the bank.

Societies flourished in every Fraser watershed, mainly due to the abundance of salmon, and along the entire coast. The people provided the first fur traders and explorers with quantities of fish and game and other foods, without which their missions would have been very brief.

1810 – 1880

Hudson’s Bay Company

Hudson’s Bay Company Forts were operating throughout the mainland and on the coast – there were dozens by 1858. They relied on trading salmon for their staff to keep themselves profitable. So many tens of thousands of fish were traded to them, that the Tribes suffered hunger when fish returns were small. But at those times, the Forts wouldn’t trade their supplies of food to Native people.

1832

Extortion at Kamloops

Around 1832, the Tribes who assembled at Pavillion refused to trade fish to Fort Kamloops. In response, the chief trader told them a smallpox epidemic was on its way, and succeeded in trading them 10,000 salmon for the only vaccine available. No epidemic came at that time.

1849

Colony of Vancouver’s Island

Vancouver Island is named an official colony of Great Britain, with the Hudson’s Bay Company as government.

The Company has a mandate to settle British citizens on the Island.

1850

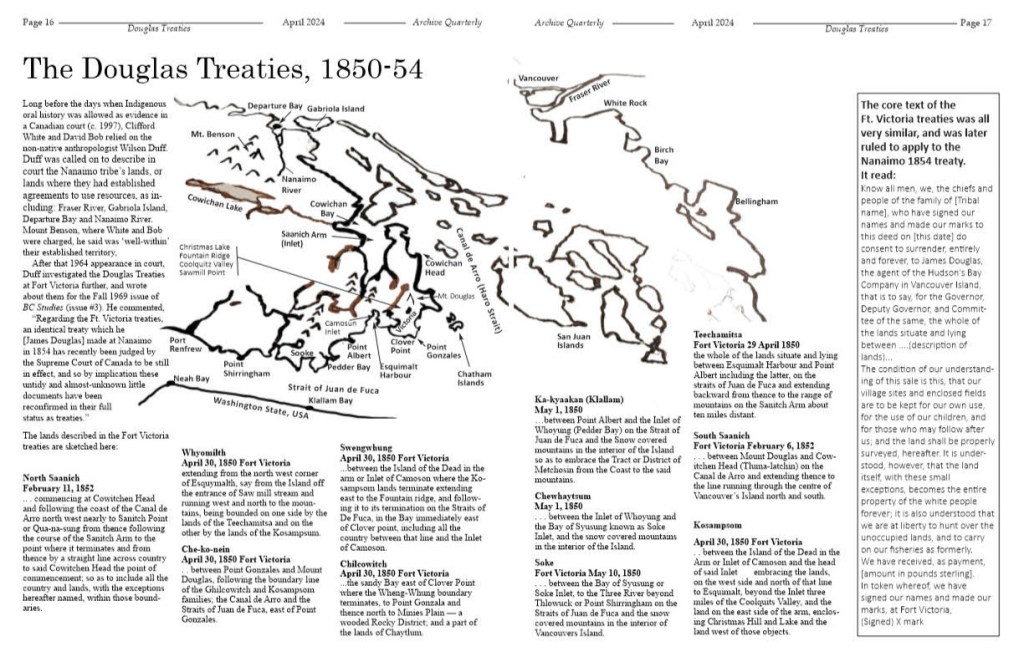

Douglas Treaties at Fort Victoria

Fourteen land-cession treaties were negotiated between several Vancouver Island tribes and HBC under James Douglas. These were not recognized as treaties by government fish and wildlife officers until the case of White and Bob succeeded in Canadian courts in 1964 and 65. The main provision of the treaties was for the hunting practices and fisheries to “carry on… as formerly.”

1866

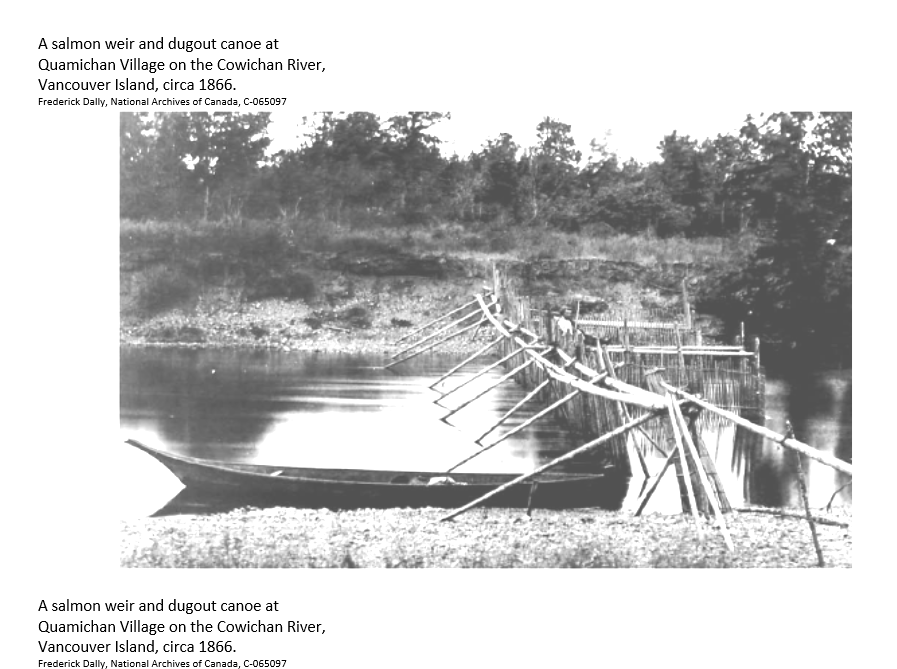

A salmon weir and dugout canoe

at Quamichan Village on the Cowichan River, Vancouver Island, circa 1866.

1893

British Columbia Fishery Commission Report 1892

56 Victoria Sessional Papers (No. 10c.) A. 1893 Printed 1898 . 450 pages

W.M. Smith, Deputy Minister of Marine and Fisheries

“From this small beginning in 1876, the salmon canning industry has grown to the first magnitude, the pack of salmon in the Province of British Columbia in the year 1889 amounting to 419,211 cases, representing a value of $2,414,655. This was the product of thirty canneries, of which sixteen were operating on the Fraser River.”

1907

Dominion – British Columbia Fisheries Commission

By the turn of the 20th century, commercial salmon fleets fishing mixed stocks at the mouth of the Fraser River had brought down the single most productive salmon watershed on the planet. Restrictions on fisheries started with outlawing the terminal fisheries practiced by Indigenous communities in-river: a selective fishery managed by weir systems.

1911

Fort St. James Barricades Agreement of 1911

June 19

“We the undersigned Chiefs… agree that in Pinche Creek and Tacha River, nets shall be prohibited and used only in Stuart’s Lake..

“The Government will be required to furnish one net to each family, length of net to be two hundred feet long and nine feet deep, and twine sufficient to keep them in good repair.” “

1913

Hell’s Gate Slide on the Fraser River

Rail-building crews in the Fraser Canyon are blasting away rock, and it all goes into the river throughout the salmon upmigration. The blasting triggers a slide into the river, indicating the precarious practice.

Catastrophic Hell’s Gate Slide on the Fraser River

The rock slide at Hell’s Gate completely blocks fish passage through the Fraser canyon. The slide was a direct result of CP Rail blasting a path for train tracks, and added to the railway’s dumping of rock into the canyon that had been going on for over a decade. Men worked for weeks to bring salmon in baskets past the slide. The fish backs blackened the river for ten miles downstream.

Seven Chiefs of the Upper Sto:lo take out an advertisement in The Chilliwack Progress, claiming that they would continue to fish while Fisheries attempted to close all fishing in the canyon. They stated, “We also claim that all the fish we catch in the whole season does not amount to the number caught in one day at the mouth of the river by the fishermen employed in catching for commercial use.”

1916

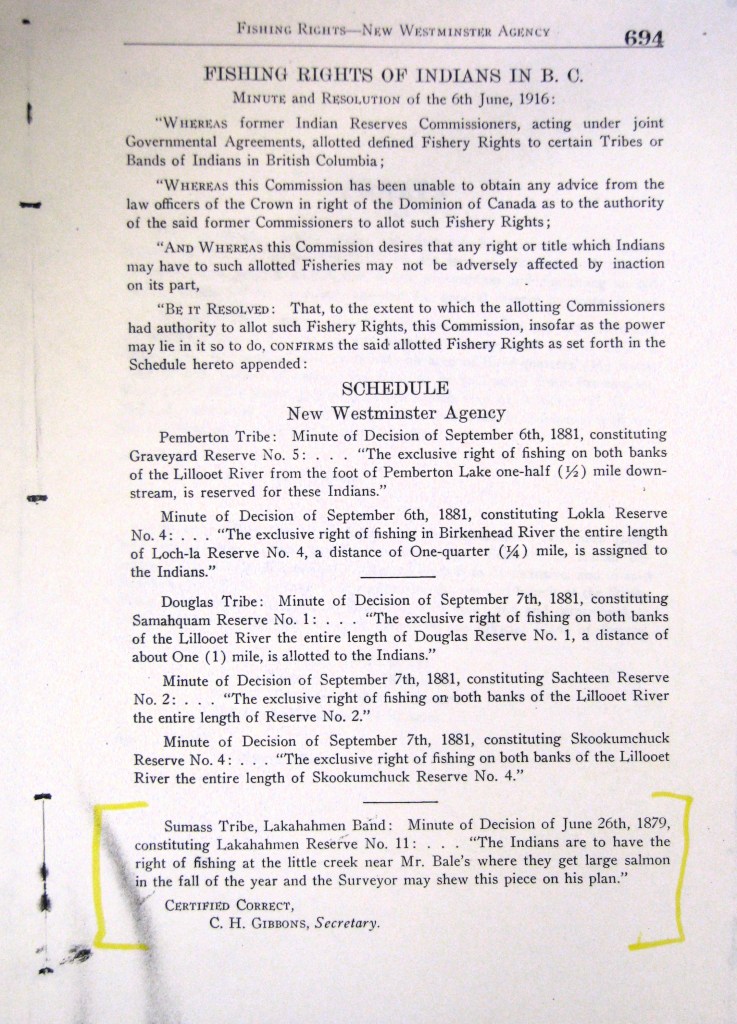

Fishing Reserves – Indian Reserve Commission

The McKenna-McBride Commission, 1914-1916

New Westminster Agency – including Pemberton, Sliammon, Squamish, Musqueam, Tsawwassen, Sto:lo, more.

1931

Native Brotherhood of British Columbia

forms among Haida and Tsimshian, soon extending among more Coastal Nations and eventually including mainland interior tribes. Operating initially to protect Indigenous commercial fishermen’s livelihoods, NBBC evades the Indian Act ban on Indigenous gatherings by prominently displaying British and Christian symbols, and singing Onward Christian Soldiers at the start of every meeting.

After amendments to the Indian Act in 1927 had prohibited gatherings of more than three Native people, and prohibited lawyers from taking Native clients to advance the interests of their Bands, ie, land rights and human rights, the Native Brotherhood formed as a business collective concerned with commercial fishing.

1952

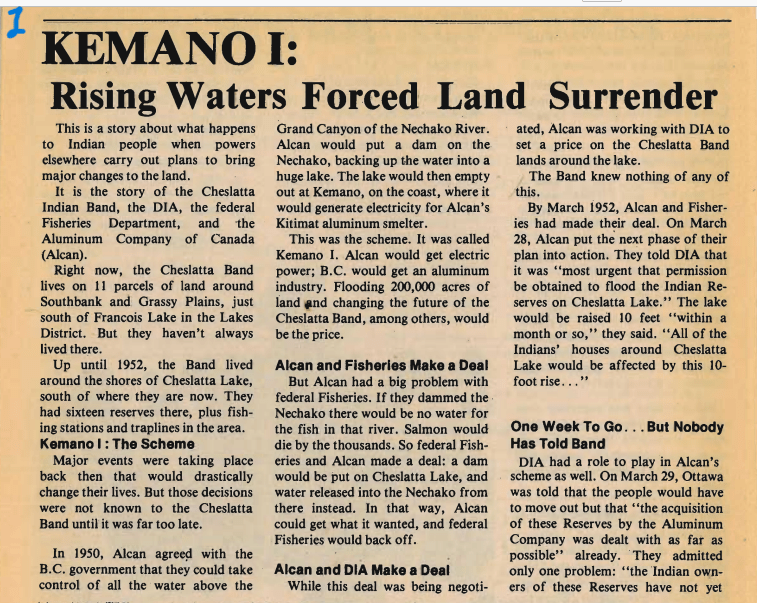

The Cheslatta Dam was sealed across the Nechako River, April 8.

This hydroelectric operation was built to power Alcan’s Kitimat aluminum smelter. The reservoir flooded the Cheslatta People’s sixteen reserves around the shores of what had been Cheslatta Lake, where fishing salmon was a mainstay.

1975

R. v. Jack et. al.

Eight Cowichan people were charged with fishing for food, on the Cowichan River, at a time when DFO had closed the river during a record-low salmon return. They were convicted. They appealed.

They did not rely on any aboriginal title or rights; and they had no treaty rights.

They argued that Article 13 of the Terms of Union (when BC entered confederation with Canada in 1871) protected their right to “a policy as liberal” as previously afforded by the Colony. Before Confederation, the Cowichan’s right to fish without regulation was the Colony’s policy.

They were fighting for standing to invoke constitutional provisions in their defense. The Supreme Court of Canada recognized that, over BC’s objections.

But the Cowichan fishermen’s lawyer made a critical concession: that conservation purposes would govern any Indian fishing rights. …The SCC found “any limitation upon Indian fishing that is established for a valid conservation purpose overrides the protection afforded by article 13,” and therefore no harm had been done to any aboriginal right, so the conviction remained.

British Columbia Provincial Court, Heard Prov. J., 1 May 1975

Indians — Treaty Indians fishing for food in restricted area — Absence of aboriginal rights — Guilty on charge under the Fisheries Act, R.S.C. 1970, c. F-14, s. 19.

“Eight Indians within the meaning of the Indian Act and registered members of the Cowichan Indian Band were charged under s. 19 of the Fisheries Act. It was admitted they fished for or had salmon in their possession for food purposes. The area where the fishing took place had been closed to all salmon fishing by order under the British Columbia Fishing Regulations. It was argued the Terms of Union of British Columbia and Canada had preserved aboriginal rights in Indians to fish for food at any time.”

“Held, the accused were guilty. They were unable to show any treaty, statute or agreement having statutory effect conferring upon them the right, or any aboriginal right, to fish as they saw fit in contravention of the Regulations made under the Fisheries Act. Although in former times there may have been a policy allowing considerable freedom of action that does not create legal rights which can be relied upon when the authorities decide different policy considerations must be applied because of a change in the situation.”

The Jack case, as decided above, was appealed and a new decision was made in the Supreme Court of Canada, 1980.

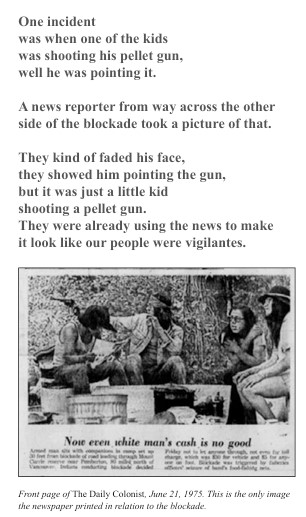

Lillooet Lake Roadblock, 1975

when DFO officers raided the Elders’ fishing spot and cut their nets to protect a commercial

Chinook hatchery that supplied Birkenhead stock to fish farms around the world.

Alvin Nelson, Wenemqen of Tilalus, Lil’wat, spoke to Archive Quarterly about his memories of the 1975 roadblock.

Stumps washed up on the shore of Lillooet Lake where the old people used to use gill nets in the deep water. Extensive clearcut logging on steep slopes further up the valley has led to major erosion and slide events, creating a new bank of accreted land which extends into the lake where the best net fishery used to be.

Survey of Native Rights as they relate to Fish and Wildlife Protection in British Columbia

By K. Krag, Protection Services – Enforcement Section, Report for BC Fish and Wildlife Branch, Department of Recreation and Conservation, August 1975

1979

R. v. Bob

“The charge arose out of an incident July 17, 1978, when Lillooet arose Indians defied a 2-day closure on the Stuart Lake run by the Department of Fisheries. Bradley Bob, fishing on the Bridge River Band side of the river, happened to be the one charged. On the Fountain Side, Victor Adolph Junior was charged on the same count, though his charge as well as seven other Lillooet area Indians will be determined by the outcome of the Bob case.”

Dipnetting for salmon at the Bridge River fish rocks on the Fraser River, where the Bob case (above) originated.

These salmon are landlocked. They are commonly called “Kokanee” salmon. These fish spawn hundreds of feet below the surface, and then float to the surface. The winds across the lake blow them in to shore, in mid-winter – a perfect time for fresh fish!

1983

Peters v. British Columbia

BCSC .1983canlii348

The petitioners are members of the Ohiaht Indian Band living on its reserves in the

Barkley Sound area on the west coast of Vancouver Island. They say that, from time

immemorial, an important part of their diet has been clams gathered from a beach on

Santa Maria Island, which is a short distance offshore from Vancouver Island, close to one

of the band’s reserves. The respondents Dunsmore have applied to the minister under the

Land Act, R.S.B.C. 1979, c. 214, to grant a licence to use the foreshore of that beach for

the purpose of using it as an experimental area for commercial clam production through artificial feeding. Such use, the petitioners say, would prevent the band members from

using the beach as they always have and would interfere with their traditional form of

conservation, i.e., never taking so many clams as to deplete the stocks. The right to use

the beach in that way is asserted to be an aboriginal right within the meaning of s. 35(1) of

the Constitution, which the petitioners expect will be identified and defined by the

conference to be held pursuant to s. 37 and thus will, beyond question, then be protected

by the Constitution.

Report from the Indian Fishery Working Committee

INTRODUCTION

At the Native Brotherhood of British Columbia’s 1982 Annual Convention, a resolution was passed by the delegates calling for the Brotherhood to host a Conference of all B.C. Tribal Councils and Independent Bands to discuss the recommendations of the Pearse Report for the Indian fisheries and to seek a process for Indian people to achieve their goals in the pacific fisheries.

The Aboriginal Council of B.C. offered to best the Conference, with the Native Brotherhood’s agreement, and the meeting was held May 26 and 27, 1983 in Vancouver, B.C.

Issues relating to the Pearse recommendations, the Constitutional process and the relationship between Coastal and Interior bands were discussed at the Conference, and a draft proposal was developed, “Proposed Negotiating Process for an Interim Solution for Management of the Indian Fisheries.”

1985

Pasco v. Canadian National Railway Co.

BC Supreme Court

This was an application by a native band for an interlocutory injunction restraining the C.N.R. from

proceeding with the construction of its twin tracking program along an eight mile stretch of the

Thompson River in the vicinity of the band’s reserve No. 5. In 1923 the C.N.R. was granted a right

of way through the band’s reserve No. 5 for railway right of way purposes. The right of way

subsequently was the subject of a Crown grant to the C.N.R. in 1924.

For most of its length one side of that right of way was formed by the high water mark of the river. The widening of the railroad bed in that stretch to accommodate a second track involved the replacement of rock fill between the existing mainline and the river. Since the fill would encroach upon the river bed in several locations, the band contended that such encroachment would interfere with their traditional fishing methods and the supply of fish. The band opposed the C.N.R.’s construction on the ground that their property right in the river itself and the bed thereof would be affected, and that under the terms on which British Columbia joined Confederation it had been agreed that the customary fishing grounds of the natives would be preserved. The band also asserted aboriginal title to the river fisheries.

1986

BC Aboriginal Peoples Fisheries Commission

Minutes of AGM, October 1986

Discussion of fishing charges, on-reserve fishing bylaws, the Sparrow case, more.

Indian Reserve Boundary Review

A re-assessment by federal departments of Justice, Transport, Indian Affairs, Fisheries and Oceans, Attorney General, and others, in an attempt to quash on-reserve fishing bylaws.

Identification of “navigable waters” as “provincial highways” through Indian Reserves: if a stream is navigable by canoe.

Inter-departmental communications, 1986. 30 pages.

BC Aboriginal Peoples Fisheries Commission – Review and Report on BC Aquaculture

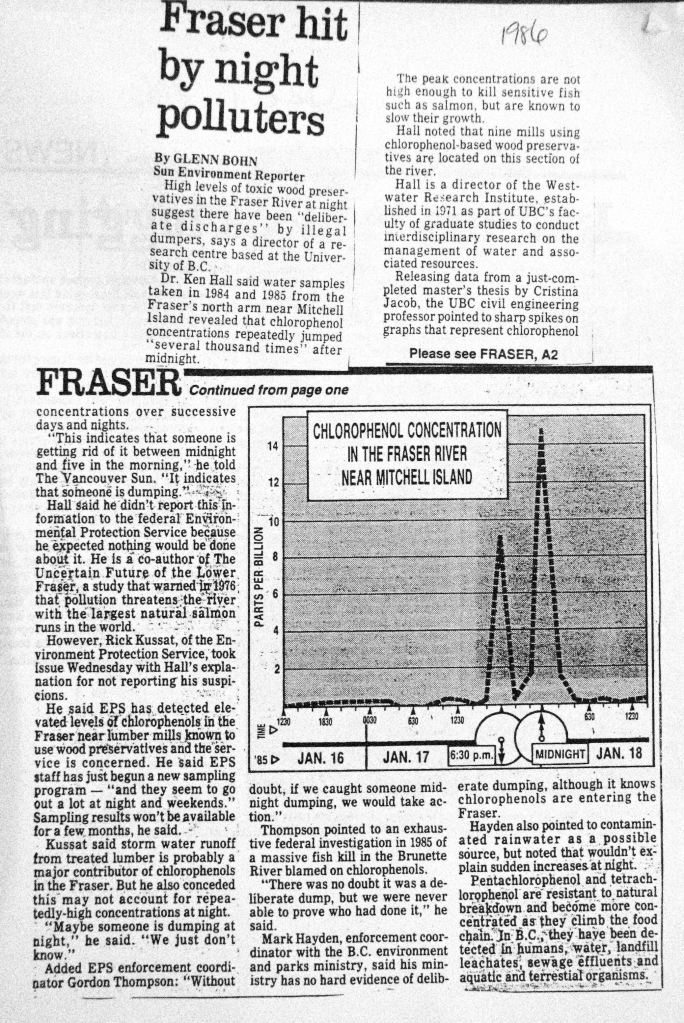

Night Pollution from Pulp Mills into Fraser River

1988

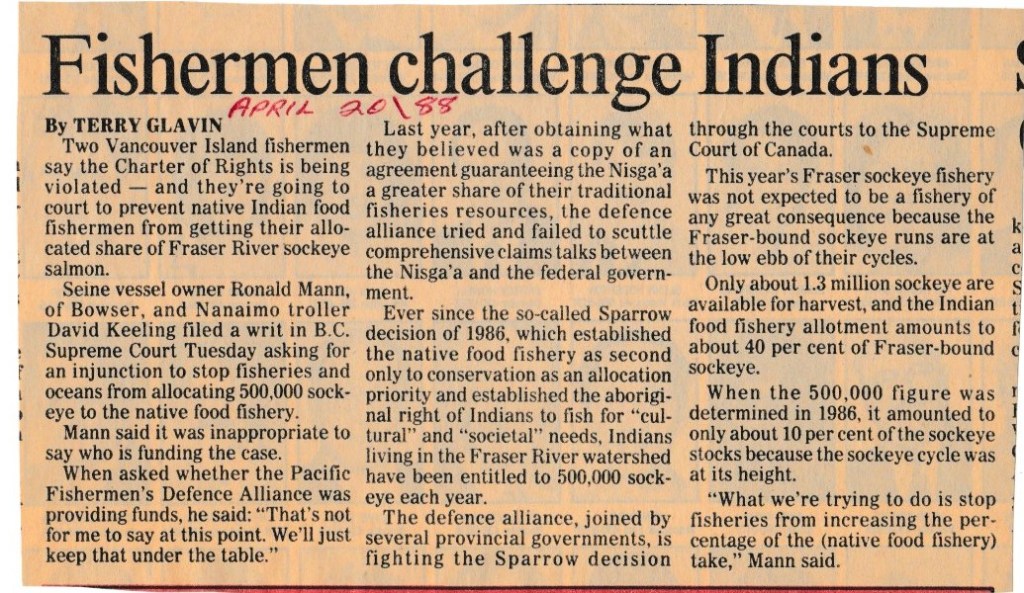

The Vancouver Sun: “Fishermen challenge Indians”

by Terry Glavin, April 20, 1988

Re. Sparrow decision

1989

Inter-Tribal Fishing Treaty

of Mutual Support and Understanding

The originating Parties to this Treaty shall be the following Indian Tribal Nations:

Cariboo Tribal Council; Carrier-Sekani Tribal Council; Chilcotin Ulkatcho-Kluskus Tribal Council; Kootenay Indian Area Council; Lillooet Tribal Council; Nicola Valley Indian Administration; Nlaka’pamux Nation Tribal Council; Okanagan Tribal Council; Sto:lo Nation Society; Sto:lo Tribal Council; Shuswap Nation Tribal Council. Each Tribal Nation represents the interests of its membership for the purposes of this Treaty.

Takla Lake, in the Stuart Lakes system

1990

R v Sparrow

1990 decision Supreme Court of Canada

Ronald Sparrow of Musqueam was fishing with a wider net than government regulation allowed. He was charged in 1984, and convicted in a BC court where the judge ruled he had no treaty rights, so Section 35 did not apply to him or protect an Aboriginal right to fish.

He appealed, maintaining that his Aboriginal right to fish cannot be infringed by provincial or federal legislation. However, his lawyers conceded in pre-trial motions that “conservation” takes priority over any kind of fishing, as had just been contemplated in the Cowichan fishing case, Jack, 1979.

The court now found a general principle: that infringement of Aboriginal rights can be justified, if there is a valid crown objective.

Sparrow’s conviction was set aside; his appeal was dismissed; and the case was sent back to trial, to answer the question of whether the government legislation could be justified in its infringement of his Aboriginal right, according to the new test the court defined. There was no re-trial.

Still, in an improvement from the see-saw of food gathering rights recognized and then denied in hundreds of provincial and federal courts, the SCC determined that Aboriginal rights to fish for food, social and ceremonial purposes are recognized, without a treaty.

Since the province had for a century criminalized native people for fishing for food, previous courts had held that this right was extinguished.

In Sparrow, the ruling reads:

“The test of extinguishment to be adopted, in our opinion, is that the Sovereign’s intention must be clear and plain if it is to extinguish an aboriginal right.”

And, “Historical policy on the part of the Crown can neither extinguish the existing aboriginal right without clear intention nor delineate that right.”

And, “The constitutional nature of the Musqueam food fishing rights means that any allocation of priorities after valid conservation measures have been implemented must give top priority to Indian food fishing.”

And then, “Aboriginal rights can be infringed with “justification.” And, “The phrase “existing aboriginal rights” in S. 35 of the Canadian Constitution, 1982, must be interpreted flexibly so as to permit their evolution over time.” And, “Aboriginal rights will be proven on a case-by-case basis.”

The Vancouver Sun: Confrontations feared over fishing rights

May 19, 1990

The Vancouver Sun: Court ruling brings peace, fisheries official claims

By William Boei, August 5 1990

1992

Managing Salmon in the Fraser. Report to the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans on the Fraser River Salmon Investigation.

Peter H. Pearse.

“In the summer of 1992, early runs of sockeye salmon reached their spawning grounds in the upper reaches of the Fraser River in much smaller numbers than expected, giving rise to considerable anxiety and debate.” With Dr. Peter Larkin for scientific and technical advice.

1995

R. v. Jack, John and John

Cars, boats, retired BC ferries, and other garbage can be found dumped along the banks of the Fraser River throughout the lower reaches. Photos: Kerry Coast

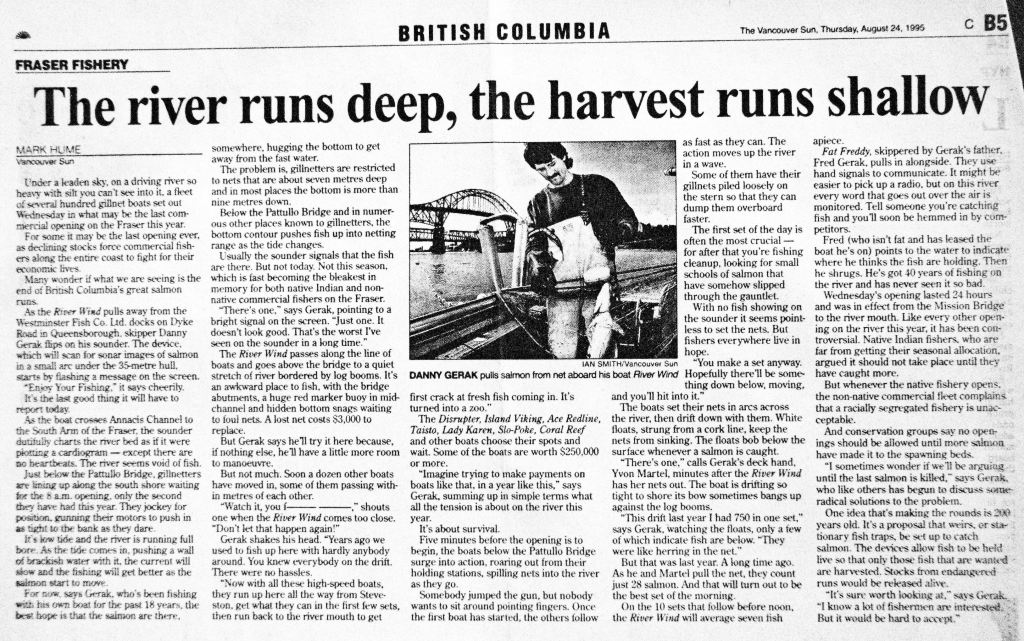

The Vancouver Sun: River runs deep, harvest runs shallow

August 24

1996

The van derPeet trilogy

At the Supreme Court of Canada, the following three cases were decided together on August 21, 1996.

Together, they are known as the “Van der Peet trilogy.”

R. v. Gladstone

““…confirming the existence of an aboriginal right of the Heiltsuk to sell herring spawn on kelp for sustenance purposes.”

Aboriginal rights to sell fish allow for subsistence harvest, enough to buy bare necessities. When subsistence rights are limited by government closure, the people should be compensated.

R. v. NTC Smokehouse

A question of the Opetchesaht and Sheshaht right to sell their salmon to the NTC Smokehouse Ltd. seafood company drove this case to the Supreme Court of Canada. Commercial fish sale is not an Aboriginal right for these people.

R. v. van derPeet

Mrs. van derPeet, a Sto:lo woman, sold ten salmon to a family friend. She was charged with illegally selling fish, contrary to state legislation. She argued that she had a right to sell the fish, for $10 each, as a form of food, social, and ceremonial uses – the household she sold the fish to was part of her social network.

The Supreme Court justices said they must determine the precise nature of the claim being made, taking into account such factors as the nature of the action said to have been taken pursuant to an aboriginal right, the government regulation said to infringe the right, and the practice, custom or tradition relied upon to establish the right.

They decided: “an aboriginal right must be part of a practice, custom or tradition which was an integral part of the distinctive aboriginal society claiming the right, prior to contact with Europeans.”

1998

The Standing Senate Committee on Aboriginal Peoples

to examine and report upon Aboriginal self-government. OTTAWA, November 4, 1998

WITNESSES:

Christine Hunt, First Vice-President, Native Brotherhood of British Columbia

Greg Wadhams, Namgis First Nation

Victor Kelly, Spokesperson, Allied Tribes Tsimshian Nation

Chief John Henderson, Campbell River First Nation, Kwakiutl District Council – “It is a sad day when the people in your villages come to you because they cannot pay their mortgages. I am the leader of a proud people. It is difficult for them to belittle themselves by going to the welfare system, after they have sustained themselves all these years up until now. The dilemma has hit us hard.

“Policies put in place by the Department of Fisheries and Oceans, as well licensing programs, are divide and conquer tactics hat give one group of people a right over another group of people. Yet, we are the same nation. That is wrong.”

2004

Sto:lo Commercial Fishery

The Abbotsford Times, August 3

2008

Fraser River Salmon Conservation and FSC Management Approaches meeting,

DFO and First Nations, Richmond BC, April 3 2008.

DFO Presentations: Les Jantz, 2008 Fraser Sockeye; Barry Rosenberger, DFO responses; Paul Kariya; Barry Huber

Discussion:

“We’re just fishing for unemployment stamps now.” – Chris Cook

“The test fishery will deliver some 42,000 fish as private property to non-First Nations before First Nations priority needs are met. We propose that First Nations become the test fishery, counting those fish in their allocation, and DFO pay them to provide the data.” – Ken Malloway

“Does DFO plan to require on-board cameras to address high-grading in Area F troll and sport vessels?” “ There are no plans for cameras but discussions are going on regarding monitoring standards…”

“After all these problems have been created by others, DFO sends us off to meetings to come up with a fix. You’re killing us.” – Stan Hunt

“We’re hearing it’s about conservation, but First Nations are taking the biggest hit, while sport fishermen don’t even report their catches.” – Arnie Lampreau

“We know government wants to modify and extinguish our traditional right. So what is meant by “sharing principles”? All the principles are already in the Fisheries Act.” – Dan Smith

“How are we supposed to live? We are cut off from our traditional fishery while DFO allows sport fishermen to fish from the Queen Charlottes right up the Fraser River snagging fish from stocks that are in trouble.” Gerald Roberts

CN derailment at Lytton during the summer salmon runs

At the confluence of the Thomson and Fraser Rivers, the railway bridge collapsed and several train cars were swept into the Fraser. Food fishing was suspended for the week while fish downstream were tested for coal residue, spilled from the train cars.

2009

Pilot Sales Program – Economic Opportunity Fisheries

2010

Paddle for Wild Salmon

Biologist Alexandra Morton rafting down the Fraser River. Arriving at Jericho Beach in Vancouver, the hundreds of people on the “migration” campaign marched to the Cohen Commission of Inquiry into the Fraser Sockeye Collapse of 2009, downtown. Photo by Kerry Coast.

Pink salmon ascending at the Bridge River near Lillooet.

2011

Lax Kw’alaams Indian Band v. Canada

TSIMSHIAN at the Supreme Court of Canada

The community spent one year in trial and a million dollars aiming to prove their continuing right to commercial harvesting and sale of “all species of fish” within their traditional waters.

They showed the only Reserves made out for them were located at their fishing places, on the salt water. They showed that eulachon grease was key to their commercial and cultural economy.

The courts refused their evidence and did not find any liability on the part of the government to protect the Lax Kwalaams village mainstay – on the coastal waters, where their reserves are – except to allow a communal fishing license for food, social and ceremonial purposes.

The judge stated that, “the Coast Tsimshian were not a trading people.”

2017

Lax Kw’alaams turned down a $1billion offer from Petronas to build a Liquified Natural Gas terminal in their waters.

“The salmon is worth more than that to our people,” said community member Eric Gray.

2019

The Nass Region ~ Snapshots of Salmon

Population Status, TECHNICAL REPORT · 201

2020

‘Namgis First Nation v. Canada

(Minister of Fisheries, Oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard, and Mowi Canada West Ltd. (formerly Marine Harvest)

Federal Court of Appeal

In 2017 Namgis people carried out an occupation of a fish farm resulted in court injunction to remove them from their occupation of the fish farm site, where Namgis said they have jurisdiction.

“I am not moving until my chiefs are satisfied that this salmon farm Licence of Occupation has been cancelled,” said Chief Ernest Alfred, “I am fighting for my life”

He stands in solidarity with his neighbours in Kingcome Inlet, whose territory covers the Broughton Archipelago. The Musgamagw Dzawada’enuxw have said “NO!” to salmon farms for over 30 years, served the industry with multiple eviction notices and were sued by Marine Harvest for boarding a nearby farm in 2016.

2021

Nuu-chah-nulth v. BC

Originating in the Ahousaht Indian Band action, and set back to re-hearing by a subsequent precedent in Lax Kwalaams, this case proceeded to win recognition of Aboriginal rights to fisheries on a commercial scale.

At the outset, the Plaitiffs explained, “After years of frustrating and unproductive fisheries negotiations at the Treaty table, Nuu-chah-nulth Chiefs decided to take their fight to the Canadian courts to prove their fishing Titles and Rights.”

Although the ruling did not break through the “frozen right” condition established in van der Peet, the people were able to prove a traditional commercial practise.

The court suggested that Aboriginal rights to a commercial fishery exist aside from treaty or title.

During the many stages of this case, as early as 1983, Nuu-chah-nulth attached a title claim to their pleadings. It was stripped from the case and set aside to be tried separately.

2023

Nuchatlaht v. British Columbia

NUU-CHAH-NULTH

BC Supreme Court

The Nuchatlaht were accepted by the BC Supreme Court Judge as the proper rights holders in the area. However, the judgment departed from the new precedent in Tsilhqot’in, 2014, where a continuous area was declared Aboriginal title lands. The BC court regressed to accept the longstanding Crown argument that Aboriginal title must mean “small spots” of settlement and continuous occupation – even in the face of government policy that caused widespread dispossession and displacement.

The Nuchatlaht claim here is to an island. They showed themselves to be the continuous and exclusive

designers, occupants, and rights-of-use holders to all the coastal landings to access the island – but the judge found there was a lack of evidence like trails and landmarks to prove exclusive Aboriginal title within the island.

The judge said that Aboriginal title does not cover water, and the test for Aboriginal title in coastal areas may need to be adapted. The judge offered to review specific sites and potentially declare small-spot title. The Nuchatlaht are appealing.

2024

Thomas v. Rio Tinto Alcan

2024 BCCA 62

Saik’uz and Stellat’en First Nations sought a judicial declaration to provide protection against the harm that the hydroelectric Kenney Dam operated by Rio Tinto Alcan has on the Nechako River, fish, and their Aboriginal rights. In a unanimous decision, the B.C. Court of Appeal found that both the provincial and federal governments have a fiduciary duty to protect the two Nations’ Aboriginal rights from the ongoing harm that the dam causes.

“1. The plaintiffs have an Aboriginal right, as claimed, to fish for food, social, and ceremonial purposes in the Nechako River watershed; and,

2. As an incident to the honour of the Crown, both the provincial and federal governments have an obligation to protect that Aboriginal right.”