Enfranchisement, denial of Indian Status, the Off-Reserve and Non-Status Indian movements

Note: these entries are not a complete history.

Canadian Legislation over Independent Peoples

Act for the Gradual Civilization of Indian Tribes, Canada, June 10 1857

Indian Act, April 12 1876

“An act to amend and consolidate the laws respecting Indians.” – Canada

Indian Act 1985

Indian Act 2010

An Act to amend the Indian Act, Bill C-428, 2014

Introduced by Rob Clarke, M.P. for Desnethé—Missinippi—Churchill River, on June 4, 2012. Bill C-428 received Royal Assent on December 16, 2014. The Act amends the Indian Act by repealing outdated or antiquated clauses and removing barriers to opportunity for First Nations.

Indian Act 2017

Indian Act timeline of amendments re women and children

– from Archive Quarterly – Summer 2024

Assimilation and Denial

“The Indian in Transition” 1964 government pamphlet

A publication of the Government of Canada. Released in tandem with the Hawthorn Report (a study on off-Reserve Status Indians, and exploration of increasing provincial roles in assimilation, service delivery off-reserve, and dispossession from federal obligations.)

The Hawthorn Report 1966 – Part 1a

A federally commissioned study into the statistics of out-migration from Indian Reserves, and reducing federal responsibilities by engaging provincial service and programs such as welfare, housing, etc. An excerpt from page 209:

“It is evident, therefore, that existing trends strongly support the policy of extending

provincial services to Indians providing suitable arrangements can be made with the provinces

and Indians are in favour of such changes. Public and parliamentary support for this policy is

found in the 1946-48 Special Joint Committee of the Senate and the House of Commons

appointed to examine and consider the Indian Act and in the representations made to the

Committee. Strong advocacy of this policy can also be found in the representations before the

1959-61 Joint Committee of the Senate and the House of Commons on Indians Affairs and in the

Committee’s recommendations.1″

Hawthorn Report – Part 1b

An excerpt from the summary:

“In 1847 Commissioners Rawson, Davidson, and Hepburn, in a Report on the Affairs of

the Indians in Canada, submitted to the Legislative Assembly, came to the conclusion “that the

true and only practicable policy of the Government, with reference to their interests, both of the

Indians and the community at large, is to … prepare them to undertake the offices

and duties of citizens; and, by degrees, to abolish the necessity for its farther interference in their

affairs.”

More than a century later, in July, 1964, the Indian Affairs Branch declared that “the basic

objective of the Federal Government in Indian Administration is to assist the Indians to participate

fully in the social and economic life of Canada.”

Something has gone wrong.”

Hawthorn Report – Part 2

1981 Census of Native People in Canada

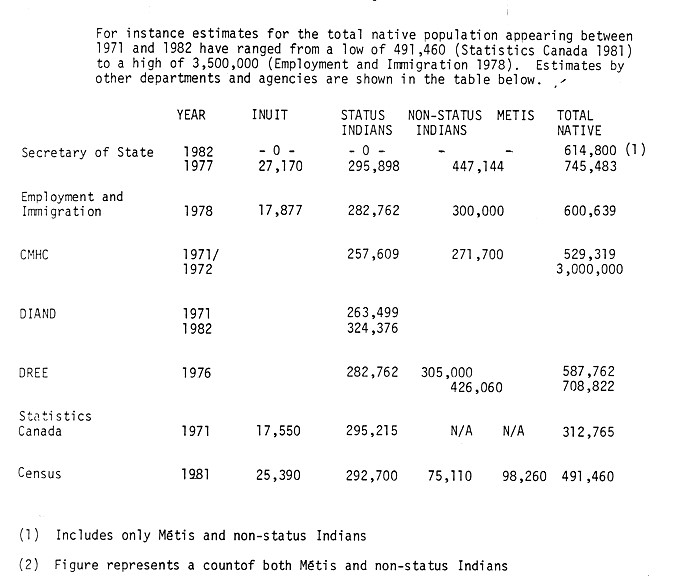

A study commissioned by the Native Council of Canada revealed that the government’s estimations of the populations of Status Indian, Metis, Non-Status Indian, and Inuit Peoples varied by Department, to a gap of 250,000 people in 1971-72. (see image excerpt below).

The study also showed that by 1977, the population of Non-Status Indians was almost double the number of Status Indians in Canada.

UNN – Endangered Peoples Presentation to First Nations Summit March 9.1994

Presented by UNN President Dan Smith. “THE FUTURE: The Year 2000. Your grandchild He asked me, who are you, what Nation do you belong to? What did you say? I said I was a citizen of no Nation. I told him that I was a creation of the Indian Act. Stripped of my identity, my birthright and my citizenship because I could not be legally registered as an Indian. I am a by-product of various pieces of legislation and policies that date back to the 1840’s when the British colonial government formally took steps to assimilate and civilize us; to legislate our Nations out of existence.”

1982-87 Canada Constitution – conferences

Introduction

Section 37 of the 1982 Constitution Act required Canada to convene a Constitutional Conference to elaborate the meaning of Section 35 concerning Aboriginal rights. This is because they were not defined, except as “existing.” While the “existing” Aboriginal rights were described in previous constitutional instruments such as the Royal Proclamation of 1763 (which was imported in its entirety into the 1982 constitution), recognition of those existing rights in a positive, descriptive manner was required by Britain’s House of Lords, on assenting to the patriation of a Canadian Constitution.

The First Minsters Conferences were held in 1983, 1985, and 1987. Aboriginal Peoples fully expected to come to a new working relationship with Canada during this process, and arrive at a full recognition of the Peoples’ rights which would be entered in Canada’s constitution by amendment. Only in 1985 were Aboriginal Peoples well-represented at the conferences.

The following documents pertain to that process.

1983

1983 First Ministers Conference – Canada’s background docs

United Native Nations Constitutional Process 1984/85 – Workplan

1985

Canada’s First Ministers Conference on Aboriginal Constitutional Matters – Indian Self-government.

April 2 1985

Verbatim transcript of Morning Sessions. Featuring remarks from:

MR. DAVID AHENAKEW (Chief, Assembly of First Nations); MR. ZEBEEDEE NUNGAK (Inuit Committee on National Issues); MR. JOHN AMAGOALIK (Inuit Committee on National Issues); MR. (SMOKEY) BRUYERE (President, Native Council of Canada); SAM SINCLAIR (President, Metis Association of Alberta); KEVIN DANIELS (Metis National Council); others

Verbatim transcript of Afternoon Sessions. Featuring remarks from:

MR. GEORGE WATTS (Assembly of First Nations); MR. HAROLD CARDINAL (Prairie Treaty Nations Alliance); CHIEF SOLOMON SANDERSON (Assembly of First Nations); MR. HARRY W. DANIELS (Vice-President, Native Council of Canada); MR. ZEBEEDEE NUNGAK (Inuit Committee on National Issues); HON. JOHN CROSBIE (Canada); MR. JIM SINCLAIR (President, Association of Metis and Non-Status Indians, Saskatchewan); MR. LOUIS (SMOKEY) BRUYERE (Native Council of Canada); JOHN AMAGOALIK (Inuit Committee on National Issues); MR. JOE COURTEPATTE (President, Alberta Federation of Metis Settlement Associations, Metis National Council); MR. FRED HOUSE (President, Louis Riel Metis Association, British Columbia); HON. WILLIAM BENNETT (BRITISH COLUMBIA)

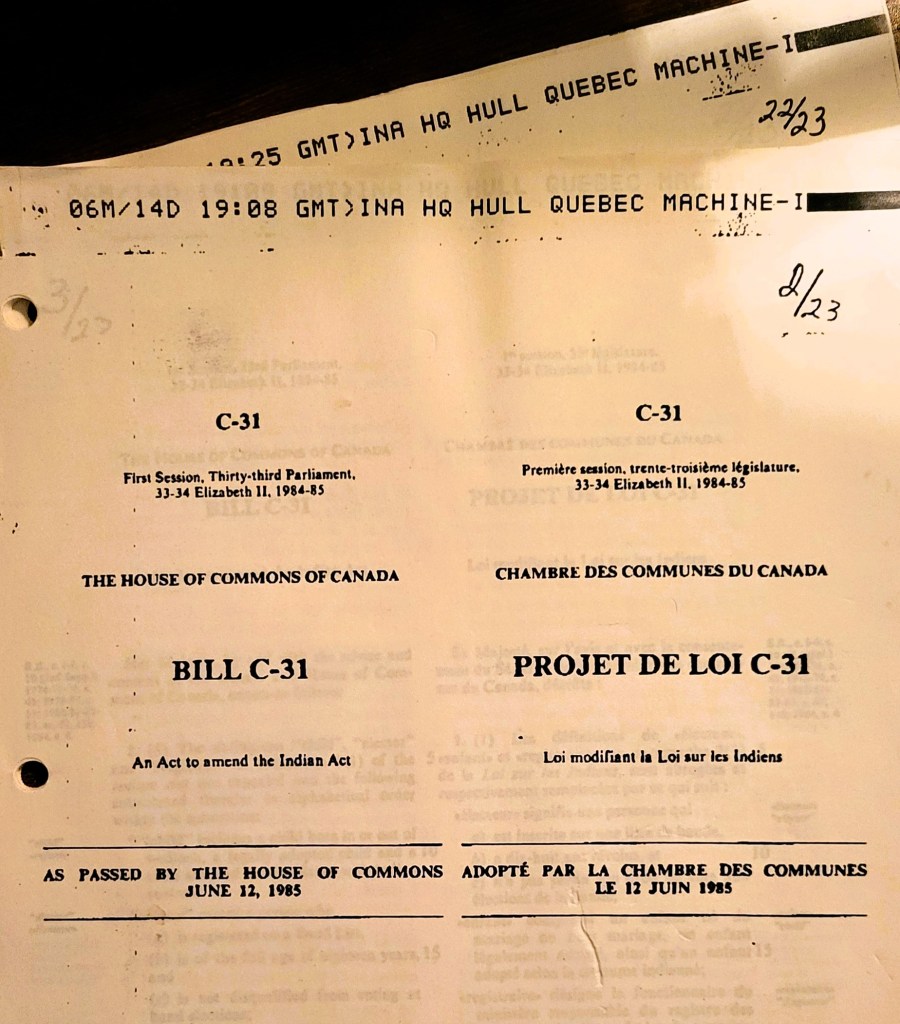

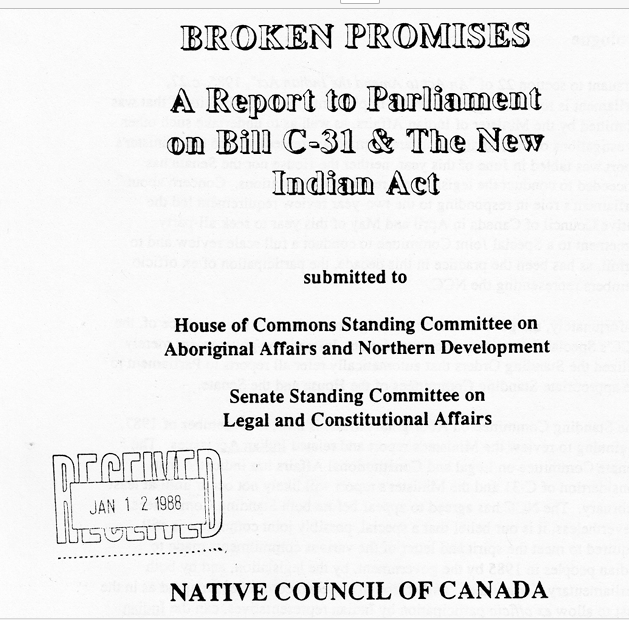

1985 Bill C-31 – An Act to Amend the Indian Act

Introduction to Bill C-31 and reinstatement in the Registrar of Status Indians

Canada invoked its Charter of Rights and Freedoms along with its 1982 Constitution Act. The Charter, to come into effect April 17, 1985, purported to end sexual discrimination in Canada. This had major consequences for the Indian Act, which discriminated severely against women: often preventing them from passing Indian Status to their children, among other disadvantages.

Bill C-31 was understood to address this kind of discrimination, to bring the Indian Act into conformity with the Charter, as well as reinstating tens of thousands of people who had not been, and could not be, registered as Status Indians for a complex web of “reasons” – all of which come back to Canada’s ongoing attempt to dispossess Indigenous Peoples of their land and rights, in this case, by refusing recognition of the individuals themselves. These further reasons are discussed in depth in the presentations shown here.

The federal government’s “consultation process” concerning the legislation was dismal. At the end, on March 20, 1985, the parliamentary Standing Committee actually cut off the speakers list addressing Bill C-31 because the vote on the Bill was occurring that afternoon.

Huge efforts, resulting in clear, consistent and actionable recommendations by dozens of organizations and Native communities from coast to coast to coast had been provided to the Standing Committee. They just were not heeded. On June 12, 1985, a totally inadequate Amendment to the Indian Act was legislated: it caused about as many new problems as it had been created to solve. For one thing, it now refused recognition of Indian Status as a function of Indian Band membership.

Inequalities and inadequacies related to citizenship in Indigenous Nations persist to this day, with Canada refusing to recognize the internationally protected right to self-determination, and only recognizing the federal Registrar as the authority on Indian Status. These injustices are present throughout each version of the Indian Act, some of which are provided on this page for reference.

The following documents pertain to the brief process during which Bill C-31 was tabled, discussed, and legislated; and then to the fallout that ensued.

Analysis of the 1984 draft Act to Amend the Indian Act

Commissioned by Peter Manywounds, Deputy to the National Chief of the Assembly of First Nations

Excerpt:

“On April 17, 1985, s.15 of the Charter comes into force and there is a consensus that this will expose the discriminatory provisions of the Indian Act to a successful legal challenge. The previous Liberal government did not want to face the uncertainty resulting from a judicial ruling…

“With less than seven months to go until the April cut-off date, it is essential that the AFN develop and quickly implement a strategy so as to ensure that the fundamental principles it espouses are reflected in any new legislation.”

Indian Act Draft Amendments – AFN & NWAC 1984

This doc is a working draft being prepared as a recommendation to the government of Canada for revision of the Indian Act. The “Act to Amend the Indian Act,” passed in1985, did not include many paragraphs of this proposed text. The “Act to Amend” was intended to remove discriminatory provisions before the April 17, 1985 deadline – at which time the Canadian Charter (part of the 1982 Canada Constitution) would come into effect.

Dene Nation to Canada re. Bill C-31

1984 memo: “…we are concerned that the legislation should provide that reinstatement be accompanied by the ability of bands to access an increased land base.”

AFN resolution to “remove discrimination”

May 1984, Edmonton

““Whereas the Federal Government has, over the past century, imposed citizenship termination and restrictive policies on our tribal nations without our consent; …”

1985

Parliamentary Standing Committee on Indian Affairs – Bill C-31, An Act to Amend the Indian Act

The following documents are part of direct presentations to and meetings of the Parliamentary Committee on C-31

United Native Nations Presentation to the Standing Committee, March 1985

Legislation of Bill C-31

With virtually no reflection of the recommendations made by Indigenous organizations.

Changes to Band Membership and Right to Register, August 1985

After the changes of Bill C-31 were legislated in a change to the Indian Act, reinstating tens of thousands of enfranchised Non-Status Indians and their families, the Department of Indian and Northern Affairs released a handbook on new Indian Act rules about Band membership.

Bill C-31 dislocated the right to register individuals as Status Indians from Indian Band authority.

1991-92 Charlottetown Constitutional Amendment

Introduction

With the failure of the First Ministers Conferences of the 1980s to positively identify the Aboriginal rights mentioned in the 1982 Constitution Act, Section 35, two new rounds of constitutional amendment began. The first, the “Quebec Round” led to the Meech Lake Accord which was filibustered by Elijah Harper in 1990, and there met its end. Quebec’s constitutional status has still not been reconciled. The second, the “Aboriginal Round,” was supposed to positively enshrine the right to self-government (not to be confused with Indian Status and Bill C-31).

A unanimous amendment was achieved by the First Ministers (Premiers of the provinces and territories), the federal government, the Assembly of First Nations / National Indian Brotherhood, the Inuit Tapiri, the Metis, and the Native Council of Canada / Congress of Aboriginal People. This amendment was put to a referendum. At the last minute, the rules of voting-in the amendment were altered, and the amendment did not pass the new formula for ratification. the Charlottetown Accord, as this round was known, failed.

The following documents pertain to development of the Charlottetown Accord and the objective of enshrining Indigenous self-government in the Canadian Constitution.

Native Council of Canada Constitutional Review Commission

1992

“Identity Rights and Values” Conference Toronto 1992

Ron George, President, Native Council of Canada, to the Policy Conference on “Identity, Rights and Values, ” Feb . 6-9, Royal York Hotel, Toronto. 1990. Speaking notes.

Excerpt: “The Native Council of Canada welcomes this long-overdue opportunity to find our place within Confederation. And as we have said over and over again, our participation in the mainstream of this country must be based on our inherent rights to self-government. participation also requires our full consent. A lot has been said lately about how Canada’s Aboriginal peoples are asking to be given Our inherent right first, and then explain what it means later. This is not quite true. If it helps, let me tell you now what we mean by the word “inherent, ” before it threatens people like the word “distinct” has threatened some people with regard to Quebec society. What we mean by our inherent right to self-government is very simple. By “inherent, ” we mean our rights are inherited. Our rights come from our ancestors, the Creator, from the land itself. Our rights are our inheritance. Unlike non-native Canadians, our rights do not come from European sources.”

News Articles re. Indian Status

Provincial and Territorial Organizations – memos 1980s

Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples 1990-96

With the failure of Bill C-31 and the First Ministers Conference, and the dubious parameters of the Charlottetown Accord…

…there was a lot of leftover momentum which Indigenous organizations, from coast to coast to coast, had gained in unifying and organizing in good faith to hold their place against Canada’s attempt to assimilate them and their lands as part of confederation – without their participation in the process.

The opportunity of the new Constitution led nowhere, except to distract and divide leadership on the ground, and now roadblocks and resistance which had appeared throughout the 1980s led to a trans-continental well of support for the Mohawk people at Kahnawake when they stood their ground against desecration at Oka. Actions to disrupt the colonizing and extractive development of Canada were widespread, and the platform of betrayal, political bad faith and refusal of recognition, racist violence, inequality, displacement, environmental devastation, and denial of title and rights had grown to epic proportions.

In 1990, the Canadian government called for a Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. Its mandate was weak. It eventually produced some thousand recommendations. The following papers were contributed to the process, among thousands, but they are here to illuminate specific issues.

Papers prepared for RCAP:

1995

“Current practice in financing Aboriginal governments: An overview of three case studies prepared for the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples.”

Focusing on the United Native Nations, Kativik Regional Government, and Siksika Nation.

Prepared by Macqueen Public Policy Analysis and Communications, For the Institute of Intergovernmental Relations, Queen’s University

1993

Committee on Aboriginal Health, British Columbia Medical Association

June 3, 1993 Presentation to RCAP in Vancouver

“The BCMA believes the land issue must be settled. …The most cogent reason for this is the poor health status of aboriginal people. … The BCMA believes there is a clear link between physical ill-health, psychiatric ill-health and loss of self respect and identity, both personal and culutural.”

RCAP’s Final Report, in its many volumes, are available online.

Off-reserve voting and elections

1999

The Corbiere decision, Supreme Court of Canada, 1999

This decision restored the right of people “not ordinarily resident on reserve” to run for office and vote in band elections.

Corbiere (Batchewana) decision: AFN response plan