These documents are provided as part of the history of interaction between Nisga’a People and the British Empire, through the Hudson’s Bay Company, and subsequently the Colony of British Columbia, and then Canada.

Methodist Missions in North Coast – letters 1884-89 re. Nisga’a.

This 100 page document was addressed to the Superintendent General of Canada, then the equivalent of today’s Minister of Indigenous Affairs, in 1889. It followed up the long-awaited but totally unsatisfactory North Coast Commission, 1888, which local leaders had been assured of addressing their many concerns.

The Methodist letter includes a searing overview from the head of the Mission, as well as lengthy testimony by several of the missionaries who lived in Tsimpshean territory at that time, especially the Reverend Thomas Crosby.

Affidavits concerning the land question – resistance to surveyors and Indian Reserves and encroachment – were translated for Chiefs and Statesmen of the Tsimpshean at Nass, Kincolith, Metlakatla, and also in cooperation with Haida who traditionally fished at the Nass and had their own annual places there. Their testimony clarifies the chain of events, unfulfilled promises, and the exact nature of the Nisga’a offer to settlers and Britain (for trade, mutuality, and peace) in the 1800s.

Witnesses include: Louis Gosnell, Arthur Calder, Chief Legaic, Job Gosnell, Chief Duduoward, Rev. Collison, Chief Herbert Wallace, Richard Wilson, David McKay, Chief Scaban, Chief Ness-Pash, Chief Clay-Tsah, Chief Tat-Ca-Kaks, more.

“The land question is not a new thing. Long before the white man made his appearance in this country our ancestors claimed the land as theirs. God, the Great Father of all the natives, gave it us. When the Hudson’s Bay Company started a trading-post on Naas River and at Port Simpson, they gave many presents to our Chiefs, thus acknowledging that the natives were the owners of the land.” – Statement of Reverend W. H. Pierce, Native Missionary, Upper Skeena.

“If we had not been here what would the Hudson’s Bay Company have come for?” – Letter of Port Simpson Chiefs And Others in Reply to Commissioner Cornwall’s Speech, at close of Port Simpson Meeting. October 20th, 1887.

“As long as I have lived I have seen my people happy in their own way on the land which God gave to our fathers. When the Hudson’s Bay Company came here to trade, nothing was said about land. Other traders also came here to trade.” – Chief Alfred Doudoward, December 3, 1888, Port Simpson.

“Another year a warship came to blow up our village, Metlakahtla. We said all right; we will stand by our land, or die by our land. Three different times war ships came to fight us; but we knew it was our land.” – Paul Legaic, December 3, 1888, at Port Simpson.

“I wish to say that every mountain and every stream has its name in our language, and every piece of country here is known by the name our forefathers gave them. And we are not satisfied with Mr. O’Reilly coming and measuring off our land. We do not understand how he comes to get this power to cut up our land without our being willing.” – STATEMENT OF CHIEF TAT-CA-KAKS. GREENVILLE, Nass River, November 7th, 1888.

“So I am surprised that Mr. O’Reilly, who came here this August, said that we were calling ours which belonged to the Queen. That the land did not belong to us. We have taken the Queen’s flag over us, and honor it. We have taken the Queen’s law to guide us, but when we took the flag and the laws we never had a little thought that in so doing we were giving away our land.” – Statement of George Gibson, Nass River, B.C., November, 1888.

North Coast Commission 1888

PAPERS RELATING TO THE COMMISSION APPOINTED TO ENQUIRE INTO THE CONDITION OF THE INDIANS OF THE NORTH-WEST COAST

Discussions (October 1888, at Kincolith and Port Simpson) and written correspondence between the Chiefs and representatives of the Nass, and two government Commissioners representing Canada’s and British Columbia’s interests in expropriating their lands and negotiating the size and location of Indian Reserves, the placement of Indian Agents, and the Indian Act.

Am-Clamman (sub-chief of Kit-wil-luk shilts) – The land belonged to our forefathers. It is like a long purse full of money, it never fails, and that is why we want to keep it. It belongs to us now, so we don’t want any strangers to get our food away from us, our own land; it has never been done before, any strangers claiming our land.

You saw us laughing yesterday when Neis Puck got up and spoke, because you opened the book and told us the land was the Queen’s and not the Indians’. That is what we laughed at. No one ever does that, claiming property that belongs to other people. We nearly fainted when we heard that this land was claimed by the Queen. The land is like the money in our pockets, no one has a right to claim it.

We all agree with what David said, that we should be paid for our land outside of what we want for ourselves. Kledach and our people are of the same nation, and we talk the same language; but we live further up the river on account of the hunting grounds, fisheries, and berries; but we always come together at Stoney Point to get our small fish, and we eat and drink together. Our houses are there, and what we use for making grease we leave there when we return up the river.

Nisga’a Petition 1913

Presented to the King of Britain’s Privy Council by the Nisga’a’s London lawyers.

Excerpts from Petition:

5. No part of the said territory has been ceded to or purchased by the Crown, and no part thereof has been purchased from the said Nation or Tribe by the Crown or by any person acting on behalf of the Crown, at a public meeting or assembly or otherwise, or by any other person whomsoever.

11. From time to time Your Petitioners have delivered to surveyors of the said Government entering the said territory for the purpose of surveying portions thereof, and to persons entering the said territory for the purpose of pre-empting or purchasing portions thereof under the assumed authority of the “Land Act,” written notices of protest…

Statement of the Allied Tribes 1916

“After the Nishga Petition had been lodged, the London lawyers of the Nishga Tribe received from the Lord President of the Privy Council a letter stating as reason for not referring it to the Judicial Committee the supposed fact that the Royal Commission appointed under the McKenna Agreement was considering the aboriginal claims, which are the subject of the Petition. Soon afterwards the Nishgas presented to the Royal Commission a memorial in answer to which they were informed that the Commissioners were not considering , and had no power to consider these claims.

“Subsequently the Nishga Petition was very fully considered at Ottawa, and as result in June, 1914, the Government passed an Order-in-Council asking that the Indian Tribes accept the findings of the Royal Commission, and agree to surrender their rights if the courts should decide that they have any, taking in place of them benefits to be granted by the Government of Canada. The Nishga Tribe and the Interior Tribes allied with them, were unwilling to accept these conditions, but made proposals of their own, …”

STATEMENT OF NISHGA TRIBE – October 1919

After the Privy Council refused to consider the 1913 Petition, the Nishga stayed in correspondence. The Privy Council had referred Nishga to the McKenna-McBride Indian Reserve Commission of BC and Canada, the “Royal Commission,” which had no mandate except to measure and cut up reserves.

Excerpt from the Nishga reply to the Privy Council:

“Also, we have now taken into account the fact that the Report of the Royal Commission ignores not only our land rights but also the power conferred by Article XIII of the “TERMS OF UNION’ upon the Secretary of State for the Colonies.

Also we have considered the fact that the whole work of the Royal Commission has been based upon the assumption that Article XIII contains all obligations of the two Governments towards the Indian Tribes of British Columbia, which assumption we cannot admit to be correct.

Also we have been unable to find by our examination of the Report of the Royal Commission that by its findings any adequate additional lands are provided for the Nishga Tribe.”

“As the Indians of the Nass Agency requested areas on the basis of 160 acres for each man, woman, and child, and all streams from their source to the peaks of mountains, with 160 acres of land on each side, it has been impossible for me to make any recommendations for these Indians as I considered that they were out of all reason.”

Agent-General Ditchburn, in a letter to BC Minister Pattullo, 1923

Indian Act 1927

After pressing their concerns over the Land Question in 1926, the Allied Tribes and the Nishga Land struggle were shut down by an amendment to the Indian Act in April 1927:

“141. Every person who, without the consent of the Superintendent General expressed in writing, receives, obtains, solicits or requests from any Indian payment or contribution or promise of any payment or contribution for the purpose of raising a fund or providing money for the prosecution of any claim which the tribe or band of Indians to which such Indian belongs, or of which he is a member, has or is represented to have for the recovery of any claim or money for the benefit of said tribe or band, shall be guilty of an offence and liable upon summary conviction for each such offense to a penalty not exceeding two hundred dollars and not less than fifty dollars or to imprisonment for any term not exceeding two months.”

Frank Calder elected MLA, 1949

FRANK ARTHUR CALDER was the First “Canadian Indian” to be elected to any Canadian parliament.

The following from his Autobiography by Edwin Peter May in his 1975 thesis, “The Nishga Land Claim 1873-1973,” at Simon Fraser University.

Personal: Born August 3, 1915, Naas Harbour, Nass River, British Columbia, to Chief Job Clark and Emily Lisk. Adopted and raised by Chief Arthur Calder.

Education: Coqualeetza Residential School. Chilliwack High School – Graduated 1937. Anglican Theological College, University of British Columbia. Graduated in 1946 with a Licentiate in Theology.

BC Government portfolios and campaigns: First elected in 1949 to the British Columbia Legislative Assembly, representing the Constituency of Atlin. Appointed as Minister without Portfolio, 1972-3, in the government of Dave Barrett. Resigned after a minor personal scandal. In the 1975 Provincial General Election, stood as a Social Credit Candidate. Defeated in the 1979 General Election.

Nisga’a Portfolios: Founder and First President of the Nishga Tribal Council, 1955 – 1974. Leader in the campaign to take the Nishga Land Claim to the Supreme Court of Canada, the “Calder Case’ resulting in the split decision of 1973. In 1974 became Director of Land and Resources Evaluation involving the Nishga Land Settlement. Honorary Chief Lissims of the Nishga Tribe.

Native Brotherhood positions: Past Secretary, Business Agent, and Chairman of the Legislative Committee, Native Brotherhood of British Columbia.

Indian Act 1951

The prohibition on lawyers working for Indigenous Peoples is lifted.

Calder v. British Columbia 1969

April of 1969, the Calder case began in Vancouver.

By the time of the BC Supreme Court decision in October, the Trudeau government had already tabled the Policy of the Government of Canada in relation to Indians – the “white paper policy.”

The BC Court of Appeal dismissed the Nishga’a appeal in 1971, and was eventually admitted to the Supreme Court of Canada later that year.

According to Douglas Sanders, one of the lawyers working for David White and Clifford Bob, and then for the Nisga’a,

“The British Columbia Indian aboriginal rights issue was first raised in the courts in Regina v. White and Bob as a defence to a charge of hunting deer out of season, contrary to provincial laws. …The appeal to the British Columbia Court of Appeal was backed by the Native Brotherhood.”

Clifford White and David Bob successfully defended their hunting rights, relying in part on their Saalequin land sale to Hudson’s Bay Company in 1854, Governor Douglas – which was finally recognized by the court as a treaty; and in part on the fact of the Royal Proclamation of 1763, which the judges accepted in their reasons in BC Supreme Court and in the BC Court of Appeal – but the Supreme Court of Canada ignored. Thus, the White and Bob case became the first to introduce land rights, which the Nanaimo defendants argued were the source of their hunting rights, into BC courts.

Sanders continues, describing what happened next:

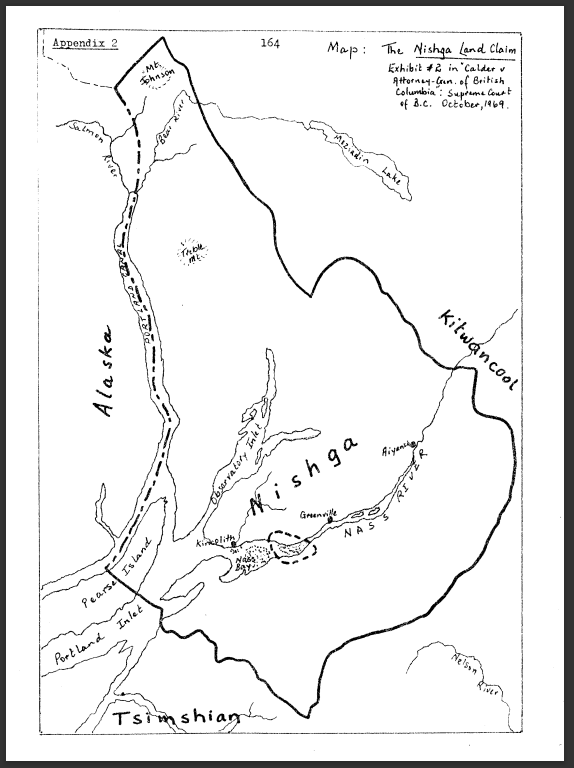

“Another attempt to litigate the land issue was decided upon. Rather than waiting to raise the legal arguments as a defence in a charge of some kind, the Indians would go to court asking for a declaration that their aboriginal rights were in existence. Since it was the Crown in the right of the province which owned the land and natural resources, a claim of Indian aboriginal title was an assertion of property rights against the province. This was so even though jurisdiction over “Indians, and Lands Reserved for the Indians” lay with the federal government. It was Worked out that Frank Calder and the chiefs of the Nishga tribe would sue on their own behalf and on behalf of the members of the Nishga tribe for a declaration that their aboriginal rights to their traditional lands had never been extinguished and continued in force. Historically the Nishga were appropriate plaintiffs. They had been very active in the early assertions of the land claim. Additionally, the area was one with few white encroachments. The case had interesting political implications. Tom Berger, who was now head of the provincial New Democratic Party, the official opposition party, was handling a case for Frank Calder, himself a New Democratic member of the legislature. On the other side was the Attorney-General of British Columbia, a member of the Social Credit cabinet, though the real claim was against the federal government, a party never directly represented in the litigation. Tom Berger did ask Jean Chretien, the Minister of Indian Affairs, to intervene in the case to support the Nishga claim, but the federal government was unwilling to play that role (as it was unwilling to play a similar role, later, in the James Bay litigation).”

- Excerpt from BC Studies, no. 19, Autumn 1973, “The Nishga Case,” by Douglas Sanders

BC Supreme Court ruling 1969

The Ruling:

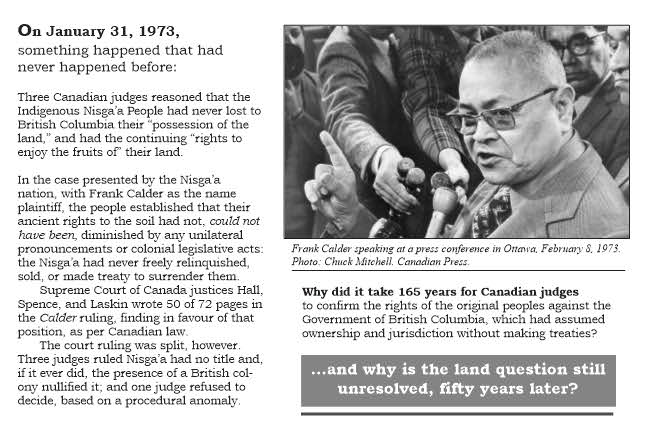

Calder v. BC, Supreme Court of Canada 1973

In the Supreme Court of Canada, the judges agreed in principle that Native title, or Aboriginal title, existed in Canadian law.

The most famous part of the ruling was written by Justice Hall, in favour of continuing Nishga title:

“…it is clear that Indian title in British Columbia cannot owe its origin to the Proclamation of 1763, the fact is that when settlers came, the Indians were there, organized in societies and occupying the land as their forefathers had done.

This is what Indian title means and it does not help one in the solution of this problem to call it a

“personal or usufructory right”.

What they are asserting in this action is that they had a right to continue to live on their lands as their fore fathers had lived and that this right has never been lawfully extinguished.”

HOWEVER – Three of the seven judges ruled that Native title had been extinguished because of the sovereignty of the Imperial British crown. The three judges who ruled in favour of continuing Nishga title, and explained it extensively, argued that a British Sovereign would have to show that they intended to extinguish Aboriginal rights by some act of purchase or legislation, in order for that original title in the land to be extinguished. One judge refused to rule on the issue, and based his opinion on a procedural aspect – the absence of a fiat, or special permission, to litigate against the crown in this way – and so he and the three judges opposed to recognizing Native title and rights formed a majority of the court and threw out the case on this basis.

Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau said, “I guess you have more rights than we thought, when we did the white paper.” A few months after that, DIA Minister Jean Chretien made a Statement on Native Claims in parliament, announcing that the government would accept Aboriginal claims for negotiation and settlement.

The ruling:

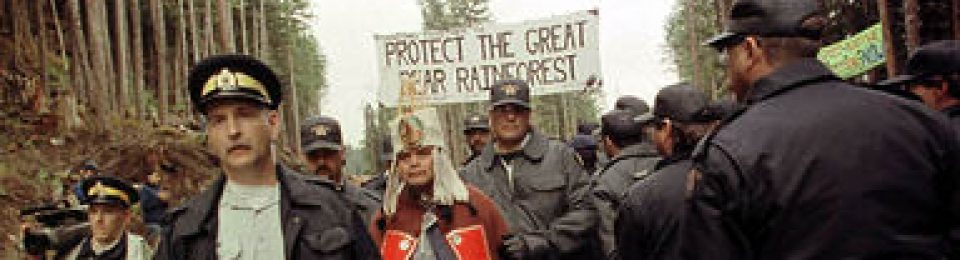

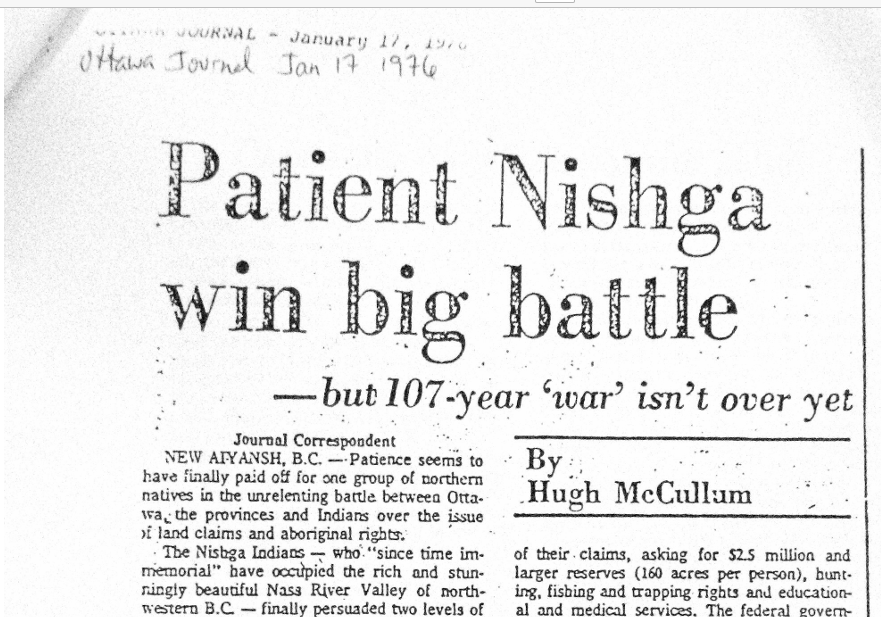

News coverage from the time:

Statement of Canada on Claims of Indian and Inuit People 1973

August 8, Government will negotiate land claims. Jean Chretien addressed the House of Commons with a policy statement: for the first time Canada will negotiate over Native land claims. Chretien referred to, “the Government’s recognition and acceptance of its continuing responsibility under the British North America Act for Indians and lands reserved for Indians.”

In 1973, the population of British Columbia is 2,367,271.

Nisga’a Declaration 1976

The Calder case had forced the Canadian government to make a new Statement on Native Claims, August 1973, and open the Office of Native Claims. The Nishga premised their entry into negotiations with Canada and BC, with the following declaration:

“In 1969, Nishga Tribal Council agreed in principle with the “statement of the Government of Canada on Indian Policy,” in the face of strong opposition from other Native Peoples across the nation. That agreed principle was incorporated in the policy statement: ‘true equality presupposes that the Indian people have the right to full and equal participation in the cultural, social, economic and political life of Canada.’ Such an agreement in principle, however, does not necessarily mean the acceptance of the steps to implement as suggested by the 1969 Policy Statement. Co-existent with the NTC agreement of the stated principle is also the NTC agreement with the Hawthorne Report, that “Indians should be regarded as Citizens Plus; in addition to the normal rights and duties of citizenship, Indians possess certain rights as charter members of the Canadian Community.”

“Undergirding the whole of the above, is the demand that, as the inhabitants since time immemoriam of the Naas Valley, all plans for resource extraction and “development” must cease until aboriginal title is accepted by the Provincial Government. Also, we, the Nishga People, believe that both the Government of BC and the Government of Canada must be prepared to negotiate with the Nishgas on the basis that we, the Nishgas, are inseparable from our land; that it cannot be bought or sold in exchange for “extinguishing of title”.”

Negotiations begin: January 1976

“I am more than pleased to advise you that for the first time the Province of British Columbia has agreed to meet with the Government of Canada to discuss the concerns of our Indian people. A historic meeting has already taken place between the Federal Minister for Indian Affairs, representatives of the Nishga People, and the Minister of my Government responsible for Native Affairs.” – Lieutenant Governor W.S. Owen, opening British Columbia’s Parliament for the Spring session in 1976, referring to the January meeting.

Nishga request reference decision on Calder 1987

With negotiations stalled for years, the Nishga Tribal Council can’t progress while the Government of British Columbia denies that they have title to their land. The decision was taken at their annual convention:

“WHEREAS in 1973 the Supreme Court of Canada left unresolved the question as to whether, in the eyes of Canadian law, the Nisga’a continue to enjoy aboriginal title to our lands and resources; and

WHEREAS the failure to achieve a resolution of this matter has been and continues to be a serious impediment to the negotiation of a land claims agreement between the Nisga’a and governments,

THEREFORE BE IT RESOLVED THAT this 30th Annual Convention wishes to obtain a speedy resolution by the Supreme Court of Canada of the issue left unresolved in the Calder case; and

BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED THAT this Convention directs the Executive of the Nisga’a Tribal Council to instruct our Legal Counsel to contact the Attorney General of Canada to seek a reference to the Supreme Court of Canada regarding the continued existence of Aboriginal Title.

Passed at a duly convened meeting of the Nisga’a Tribal Council, April 28, 1987.

After several written exchanges and a meeting in Ottawa, the Minister of Justice’s Office flatly refused:

“Other litigation involving aboriginal claims in British Columbia has shown the need for extensive evidence of both historical and current aboriginal use and occupation of lands and resources, as well as past alienations and uses permitted by the Crown adverse to the exercise of aboriginal rights. With respect, I do not agree that these are suitable matters for admissions, especially when it would involve hundreds of square miles and the interests of large numbers of Indian and non-Indian British Columbians.

The potential parties to comprehensive land claims in British Columbia would expect any reference to bring certainty to the currently unsettled issues associated with the claims. As you candidly pointed out during our meeting, current claims negotiations lack an important potential player, namely, the province of British Columbia. As I understand, the Government of British Columbia maintains that if aboriginal title subsists in that province, then all implications, including possible financial implications, lie with the federal Crown. This is not the view of the Government of Canada. I doubt that the outcome of a court reference would significantly affect our respective positions on this fundamental issue. Faced with the problems associated with the proposed reference, particularly the need for extensive evidence, and the risk that it will not significantly advance comprehensive claims negotiations, I am not prepared to recommend a reference as you propose.” – Ray Hnatyshyn, Minister of Justice, House of Commons, Ottawa, Ontario

Lock, stock and barrel. 1982

The Nisga’a Comprehensive Land Claims Framework Agreement was initialled March 20, 1991.

The Report of the BC Claims Task Force was released June 28, 1991.

BC Politicians Q&A on negotiations with Nisga’a, 1994

From the Ministry of Aboriginal Affairs, Honourable John Cashore, July 7, 1994:

9. Have you considered the tax base generated by the resource industries in the claim area which provides direct benefits to all Canadians, and how this base may be affected by land claim settlements?

– …one of the Province’s principal objectives in these negotiations is that aboriginal resources and revenues be taken into account in future funding arrangements for aboriginal governments, just as they are for municipal governments.

– Most of this tax base rests on crown land which was never legally obtained, by treaty or by war, from the aboriginal people who occupied it for centuries before European settlement. The whole point of land claims is to create some certainty and ownership and development of this land.

Nisga’a ratify Final Agreement, 1999

An excerpt from the Agreement:

MODIFICATION

- Notwithstanding the common law, as a result of this Agreement and the settlement legislation, the aboriginal rights, including the aboriginal title, of the Nisg̱a’a Nation, as they existed anywhere in Canada before the effective date, including their attributes and geographic extent, are modified, and continue as modified, as set out in this Agreement.

- For greater certainty, the aboriginal title of the Nisg̱a’a Nation anywhere that it existed in Canada before the effective date is modified and continues as the estates in fee simple to those areas identified in this Agreement as Nisg̱a’a Lands or Nisg̱a’a Fee Simple Lands.

BC Legislative debate: the Nisga’a settlement 1998-99

The BC New Democratic Party was in power for the first treaty west of the Rocky Mountains to be signed with the Province of BC.

BC politicians from other parties did not trust the NDP to guard their interests – and those of their constituents. The televised CPAC debate in the BC Legislature, January 18-20, 1999, shows the results that Canada and BC believed they had secured in the Agreement – and a total lack of interest in whether the Final Agreement was fair, equitable, or sustainable for Nisga’a people.

“The intention and purpose of negotiating treaties is to exhaustively codify rights… to exhaustively define and limit rights as modified by Nisga’a. To make sure our treatment exhaustively sets them down and then we put the law on it for certainty.” …”This is not really a nation. All I care is what limitations, restrictions, restraints upon their rights are.” – BC Minister of Attorney General and Minister for Human Rights Ujjal Dosanjh.

Lhuuxon v. BC 1999

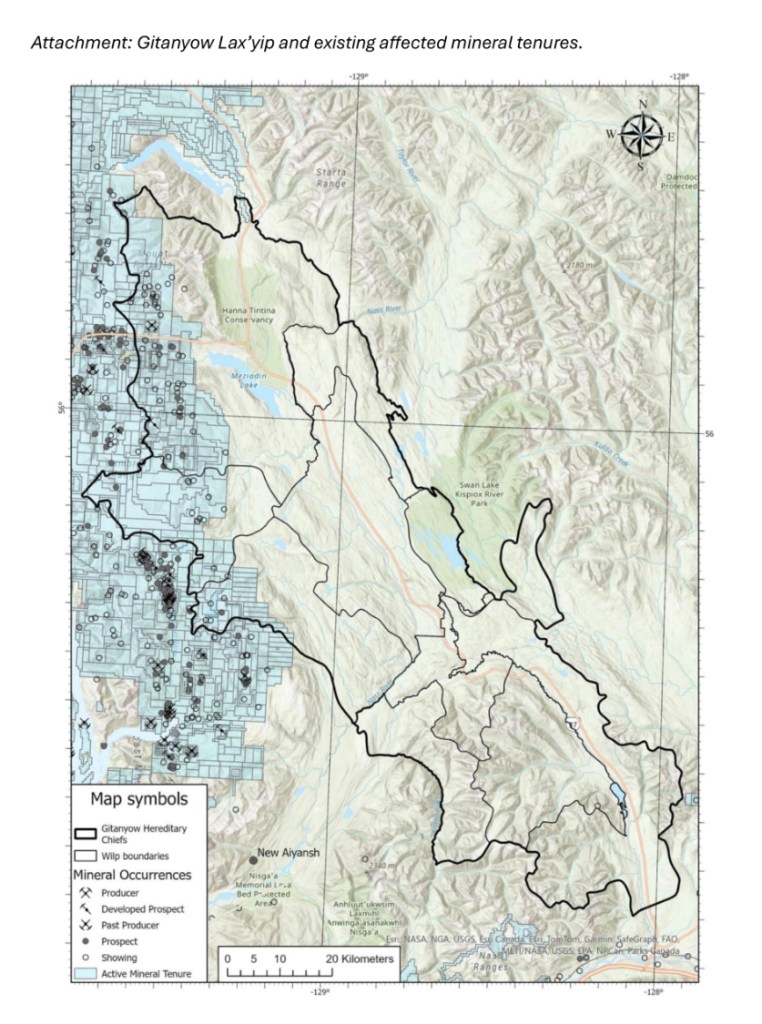

When the BC Treaty Commission adopted its terms of reference, it included a restriction that negotiations could not proceed to Stage 4 unless shared territory with Indigenous neighbours had been discussed and agreements made.

When Gitanyow entered negotiations under the BC Treaty Commission, BC had already been negotiating interests shared by Nisga’a and Gitanyow (among others), exclusively with Nisga’a. When the Agreement in Principle was announced, Gitanyow hereditary chiefs went to court for a declaration that the Province had to negotiate in good faith. They did not get one, and the BC court said:

[73] I decline at this stage to determine in a detailed way the content of the Crown’s duty to negotiate in good faith.

[75] In the result, the plaintiffs will have a declaration in

the following terms:

The Crown in Right of Canada and the Crown in Right of British Columbia in undertaking to negotiate with the Gitanyow within the framework of the British Columbia treaty process and in proceeding with those negotiations are obliged to negotiate in good faith with the Gitanyow, and all representatives of the Crown in Right of Canada and the Crown in Right of British Columbia are bound by such duty.

The Ruling:

Campbell et al. v. British Columbia, 2000

As soon as it was ratified, members of the provincial Liberal party, in Campbell et al. v. British Columbia, took BC to court over the Nisga’a Final Agreement. The applicants argued that any right the Nisga’a nation had prior to Confederation was extinguished and not preserved by the Constitution Act 1982. They claimed that it would introduce a third order of government in Canada, which would be unconstitutional.

However, the Nisga’a Agreement did no such thing, it merely incorporated the Nisga’a Tribal Council into a corporate structure with the powers of a municipal government, and in some cases it had attributes of a regional-district. The decision, however, provided an immediate judicial interpretation of the first-ever BC treaty. Campbell et. al. lost their case in BC Supreme Court, where the judge reasoned:

“The Nisga’a treaty did not purport to revive extinguished aboriginal rights. The Nisga’a had never previously ceded their rights or lands to the Crown. The right to self-government not having been extinguished, was expressly preserved by section 35 of the Constitution Act.”

32. The Treaty marks the first occasion upon which the Nisga’a have agreed to any specified impairment of those rights. Chapter 2, Section 24, states that the Nisga’a Nation’s aboriginal rights and title, as they existed before this Agreement took effect, continue “as modified” by the Agreement.

The Ruling:

The Liberals were then voted in to power in BC in 2001, and the plaintiffs in Campbell et al (Gordon Campbell, Michael deJong, and Geoffrey Plant) did not pursue their case against BC – as they now formed the government and became, themselves, the Premier, Attorney General, and Minister of Finance of British Columbia. Plant was appointed Minister responsible for Treaty Negotiations, on top of being Attorney General, and he oversaw the province-wide British Columbia Treaty Referendum in Spring of 2002.

The Agreement had been finalized for $80 million in capital transfer, over twenty years; 8% of their claimed land base, and a few side deals which included road improvements (that would be used by non-Nisga’a industries), a school, and a health station.

The agreement was signed on 27 May 1998 by Joseph Gosnell, Nelson Leeson and Edmond Wright of the Nisg̱a’a Nation and by Premier Glen Clark for the Province of British Columbia. Then Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development Jane Stewart signed the agreement for the Canadian federal government on 4 May 1999.

With more to come, news and events in the 25 years since the treaty was ratified.