Note: These entries are provided in alphabetical order, with International cases by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights below, and International Declarations below.

This is not a complete history. Uploads ongoing, check back.

Cases arising in the British Columbia courts and cases arising in Canadian courts, and International Conventions

R. v. Adams (Thomas Russel) 1984-90

Haida

“I have no option but to find that the defendant was not required to hold an Indian Food Fish Licence for the herring spawn on kelp in his possession and he is therefor entitled to acquittal on both charges.”

Ahousaht First Nation v. Canada (Fisheries and Oceans) 2004-2021

Nuu-chah-nulth

Further amended Statement of Claim, Her Majesty the Queen, 2008. In the Supreme Court of BC.

Case Summary of Federal Court of Canada ruling, 2007. Prepared by Lawson Lundell LLP, July 20, 2007

“The Federal Court of Canada recently released its decision in Ahousaht First Nation v. Canada (Fisheries and Oceans). The court considered an application by 14 First Nations represented by the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council (“NTC”) for judicial review of the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans regarding the implementation of a commercial groundfish pilot plan on the British Columbia coast (the “Pilot Plan”). The NTC challenged the Minister’s decision on the grounds that the Minister failed to fulfil his duty to consult and accommodate the NTC before implementing the Pilot Plan. After reviewing the process leading up to the Plan’s introduction Federal Court dismissed the application, finding that, although the consultation was not perfect, the flaws did not warrant changing the Minister’s decision.”

Ruling. 2009 BC Supreme Court:

“The plaintiffs in this case are the Ehattesaht, the Mowachaht/Muchalaht, the Hesquiaht, the Ahousaht, and the Tla-o-qui-aht, whose territories are located on the west coast of Vancouver Island. This case turns primarily on the claim of these plaintiffs to an aboriginal right to fish on a commercial basis.”

Ruling. 2011 BC Court of Appeal:

“This is an appeal from a judgment of Garson J. (as she then was) who made findings in favour of the plaintiff/respondents of Aboriginal rights and infringements thereof. The reasons can be found at 2009 BCSC 1494. Canada appeals from these findings.”

News from latest court rulings. Ha-SHITH-sa News. 2023, November 17.

“Nuu-chah-nulth-aht filled the Hupacasath House of Gathering on Friday, as the hundreds in attendance celebrated the court-affirmed right of five First Nations to commercially harvest fish from their respective territories.”

Alberta Indian Association et al v Canada

REGINA v. SECRETARY OF STATE FOR FOREIGN AND COMMONWEALTH AFFAIRS,

Ex parte INDIAN ASSOCIATION OF ALBERTA AND OTHERS

1982 Jan. 14, 15, 18, 19, 20; 28

Lord Denning M.R., Kerr and May L.JJ.

Attempting to stop the patriation of a Canadian constitution without any guarantees of the treaties signed by Britain, this case included the Union of New Brunswick Indians, and the Union of Nova Scotian

Indians as co-plaintiffs with the IAA.

in 1980, The application was dismissed by the High Court of Justice, Queen’s Bench Division. The applicants appealed.

This January 1982 judgment was given by the UK Court of Appeal (Civil Division), Royal Courts of Justice, London.

Bear Island Foundation and Temagami v. Ontario

(c.1985) Supreme Court of Canada

Factum of Intervenor NIB-AFN

“The Royal Proclamation applies in the land claim area. It has the force of statute. The onus is on the Respondent to prove abrogation of the procedural requirements enshrined in the Proclamation.”

“There is no case law, except the judgments below, in support of the argument that the procedural requirements of the Proclamation were repealed by the Quebec Act.”

R. v. Bob 1979

St’at’imc

Ruling. British Columbia County Court.

“The accused was charged with unlawfully fishing in contravention of a closure effected under the Fisheries Act and Regulation. The accused claimed he had a lawful excuse to fish because he was fishing pursuant to a reserve right, not an aboriginal or treaty right.”

“The historical background for the Defence… (includes) “Recognition of BC Indian Fish Rights by the Federal-Provincial Commission, prepared for UBCIC 1978. I refer to the instructions given to Dominion Commissioner, Mr. Anderson, dated August 25, 1870: “While it appears theoretically desirable as a matter of general policy to diminish the number of small reserves held by an Indian Nation, the circumstances will permit them to concentrate on three or four large reserves, thus making them more accessible to missionaries and school teachers…”

Calder v. British Columbia 1969, 1973

Following the White and Bob decision, the Nisga’a sought a declaration from the courts that their title had never been extinguished. They said their title continued, as confirmed by the Royal Proclamation of 1763. They excluded private property and areas under provincial license in their claim, and did not challenge the crown’s assertion of sovereignty.

It was an action for judicial recognition that the Nisga’a Nation’s Native, or Aboriginal, land title which had yet not been the subject of treaties with the Imperial Crown, was intact and continued to exist.

At the Supreme Court of Canada, the case was decided by the seven judges on a procedural point, not the substantive issue. The judicial views on title, which were evenly split 3-in-favour, and 3-against, and 1-declining to judge the issue, remained merely opinions.

As a result, most BC judges continue to rely on the BC Supreme Court ruling of 1969 by Justice Gould, quoted below.

Historical background, Paper: “Nishga Land Claim-1873-1973,” by EPMay 1979 SFU

Ruling. BC Supreme Court, 1969

“In this case, crown sovereignty… over the delineated lands came by exploration of terra incognita, no acknowledgment at any time of any aboriginal rights, and specific dealings with the territory so inconsistent with any Indian claim as to constitute the dealings themselves a denial of any Indian or aboriginal title.

“As the Crown had the absolute right to extinguish, if there was anything to extinguish, the denial amounts to the same thing, sans the admission that an Indian or aboriginal title had ever existed.

There is nothing to suggest that any ancient rights, if such had ever existed prior to 1871 and had been extinguished, were revived by British Columbia’s entry into Confederation and becoming subject to the British North America Act, 1867. Action dismissed.” – from Justice Gould‘s 1969 ruling.

Ruling. Supreme Court of Canada, 1973, January 31

“..it is clear that Indian title in British Columbia cannot owe its origin to the Proclamation of 1763,

the fact is that when settlers came, the Indians were there, organized in societies and occupying the land as their forefathers had done.

“This is what Indian title means and it does not help one in the solution of this problem to call it a “personal or usufructory right”.

“What they are asserting in this action is that they had a right to continue to live on their lands as their forefathers had lived and that this right has never been lawfully extinguished.” – Justice Hall,

finding in favour of Nisga’a, 1973.

Reference Decision – requests by Nisga’a Tribal Council; former Prime Minister Diefenbaker

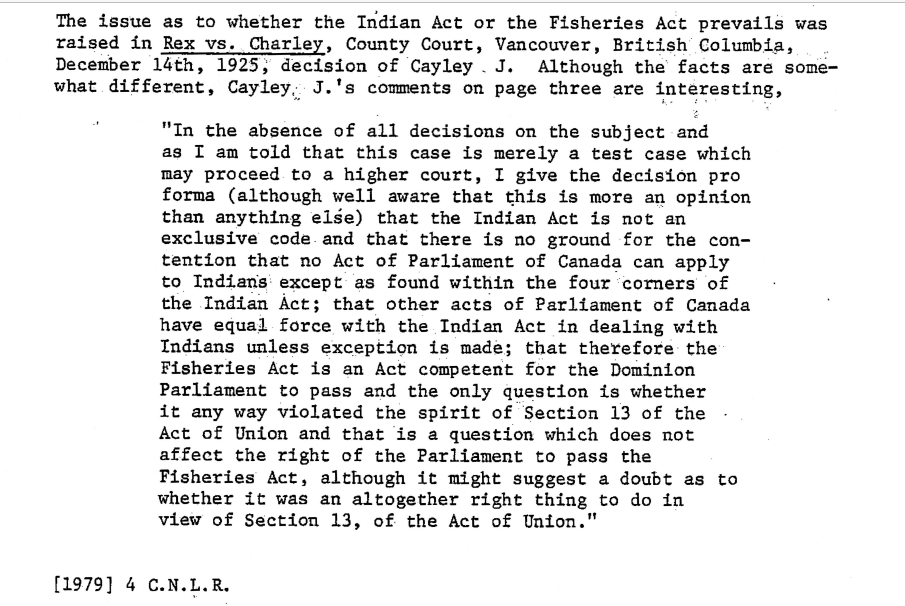

R. v. Charley 1925

Cowichan v Canada 2025

August 7, BC Supreme Court

[1240] I am satisfied that Central Coast Salish and Cowichan customary property law included law regarding proprietary collective ownership of villages. I accept that under those laws, the Cowichan had a recognized proprietary interest in the lands and waters in the vicinity of their village at Tl’uqtinus.

[1599] The SCC has yet to determine whether Aboriginal title can exist in water or land submerged by water.

[1962] As discussed in Part 5, the Cowichan had complained to Commissioner Sproat about a settler’s purchase of the Cowichan fishery. Sproat noted that the owner was absent. In January 1878, Sproat wrote to the Lieutenant Governor of British Columbia about “[t]he ancient fishing ground on the Lower Fraser of the Cowichan nation, where 700 to 1000 Indians have been accustomed to assemble and catch fish for their winter food, has been sold and now belongs to a white non‑resident. What can be done in such a matter?”

[1963] There is no evidence that Sproat investigated the Cowichan complaint at the Lands of Tl’uqtinus, and it was Dr. Brealey’s opinion that he did not.

[1972] Even after the alienation of the village site in the 1870s through issuance of the Crown grants, the Cowichan continued to use and occupy these lands annually while at their fishery on the Fraser River. Sproat documented the Cowichan’s complaint about the sale of their village and their continued occupation of it in a letter to the Lieutenant Governor on January 12, 1878: “… the old fishery station on the Fraser known as the “Cowichan Fishery” and annually used by them from time immemorial in getting fish for winter food, has been sold many years ago. The owner being an absentee, there has been no trouble about the land as yet. About one thousand Indians encamped there last season.”

Daniels v. Canada (Indian Affairs and Northern Development) 2016

Metis and Non-Status Indians

Booklet, “Understanding the Daniels Case” by BC Metis Federation. May 2016

“At its best, the Daniels ruling provides the possibility to “consider” Metis communities as self-determined and self-governing nations with a unique historical connection to the Crown and First Nations.”

Ruling. Supreme Court of Canada, 2016.

Delgamuukw v. The Queen, 1985-1997

Gitksan – Wet’suwet’en

The Gitxsan and Wet’suwet’en House Chiefs, representing 51 Clan land titles and spanning 57,000 square kilometers, sued for recognition of their land titles and their jurisdiction over those lands.

The legal actions that started this case began in 1984, with disputes of logging activity, then an attempt to register claims as property right with the Land Titles registry, in Uukw, 1987.

Over about a year’s worth of trial days, the leaders of the Gitxsan and Wet’suwet’en governments shared their elaborate systems of governance; the histories of their peoples; and the ancient evidences of their connection to the lands. Many Elders also testified.

Ruling. BC Supreme Court, 1991

BC’s Supreme Court Justice McEachern accepted that the appellants’ ancestors lived within the territory, but predominantly at the village sites. He accepted that they harvested the resources of the lands, but only to an extent compatible with bare occupation for the purposes of subsistence.

He saw no system of governance relating to land outside villages. He refused to accept that the spiritual beliefs exercised within the territory were necessarily common to all the people. He was not persuaded that the present institutions of the plaintiffs’ society were recognized by their ancestors.

He said, “they more likely acted as they did because of survival instincts.” He stated that the maintenance and protection of the boundaries were unproven because of intrusions into the territory by other peoples. The oral histories, totem poles and crests were “not sufficiently reliable or site-specific to discharge the plaintiff’s burden of proof.”

The judge did not accept the feast system’s role in the management and allocation of lands.

He concluded, “I cannot infer from the evidence that the Indians possessed or controlled any part of the territory, other than for village sites and for aboriginal use in a way that would justify a declaration equivalent to ownership”.

The BC government’s position was the same as it had been since Calder, and Martin, and everything in between: that there never had been any Gitxsan or Wet’suwet’en title, but, if there had been, it was extinguished by the presence of the crown and the government’s exercise of legislative powers without regard for them.

Ruling. BC Court of Appeal, 1993

Both the Plaintiffs and the Province appealed the BC Supreme Court decision.

In preliminary procedures, the Province retained new counsel and changed its position on “blanket extinguishment” of Aboriginal rights. The Province’s new position was that some specific Gitxsan and Wet’suwet’en Aboriginal rights continued, to be practiced on unoccupied crown lands.

The BC Court of Appeal ran a very substantial hearing, and gave a 300-page ruling, finding the appellants have unextinguished non-exclusive aboriginal rights.

Both appeals were allowed, pending a period of negotiations, requested by the court, which failed and led to further litigation, and this title case continued to the Supreme Court of Canada for a 1997 ruling.

Ruling. BC Court of Appeal, 1994

In the matter of BC forest managers proceeding with logging and “consultation” instead of negotiating a co-management regime as recommended by the BCCA.

Ruling. Supreme Court of Canada, 1997, December 17.

In 1997, SCC Chief Justice Lamer dismissed the claim to jurisdiction outright.

R. v. Dennis and Dennis

Tahltan

On or about March 11, 1974, at or near mile 3 of the Cassiar Road, Jimmy Dennis, father and son members of Tahltan, one moose was shot for the purposes of providing food for the family.

The Crown argued, as usual, that even if aboriginal rights did once exist in the Indian people of British Columbia, those rights were since extinguished. Judge O’Connor found that the province was not capable of interfering in the rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Ruling. British Columbia Provincial Court, 1974, November 25

R. v. Derriksan

Okanagan

Ruling. (1975) BC Court of Appeal.

“Section 32 of the Regulations which makes special vision for licensing fishing by Indians reinforces the concept that Indians are not otherwise excepted from the Regulations.”

Ruling. Supreme Court of Canada 1976

“[1] LASKIN C.J.C.:—On the assumption that Mr. Sanders is correct in his submission (which is one which the Crown does not accept) that there is an aboriginal right to fish in the particular area arising out of Indian occupation and that this right has had subsequent reinforcement (and we express) no opinion on the correctness of this submission), we are all of the view that the Fisheries Act, R.S.C 1970, c. F-14, and the Regulations thereunder which, so far as relevant here, were validly enacted, have the effect of subjecting the alleged right to the controls imposed by the Act and Regulations. The appeal is accordingly dismissed. There will be no order as to costs.”

Dick v. The Queen

Arthur Andrew Dick was a Secwepemc national, a member of the Alkali Lake Band. He shot one deer to feed himself and the members of his fishing party, camped towards Gustafsen Creek. He was fined $50, and he appealed.

Arthur Dick was acquitted of the charge of hunting one moose on the reasoning that provincial laws of general application cannot be applied to matters that “go to the core of Indianness,” such as fishing and hunting. This adjusted judicial reasons concerning Section 88 of the Indian Act, by identifying the fact that provincial laws about hunting and fishing are not “laws of general application” because Indigenous hunting and fishing would be disproportionately affected in comparison to the “general” population.

Ruling. Supreme Court of Canada 1985

Articles in Indian World 1980 and 1981

R. v. Douglas et al, c.1985

BC Provincial Court

Sto:lo

Defence counsel cross-examination of the crown’s witness, DFO officer Randy Nelson

“Q. In this letter you say: “neither released, so I hit their knuckles and arms harder and harder.” Do you agree with that statement?

A. Yes.

Q. Okay. Now in this letter you talk about Mr. Douglas and that’s Sam Douglas, the accused, right?

A. Yes, Your Honour.

Q. And you say as follows: “My concern …is that the D.F.O. negotiates with this animal, and that he is a representative on the Salmon Commission.” Now when you say “this animal” you’re talking about Sam Douglas, aren’t you?

A. That is correct in that letter, yes Your Honour.

…Q. Next paragraph: “If Mr. Douglas is continued to be met with, I would be most disappointed and would like to know the Department’s reasoning for this. It would make about as much sense as opening a Clifford Olsen Day Care Center.”

A That’s what the letter says, Your Honour.

Q. Now are you telling this Court, that this is humour on your part?

A. Humour… yes.”

Fletcher Challenge v Miller et al, 1991

1991, Oct 21. Supreme Court of BC. (C915008 Vancouver Registry)

Re. Walbran Valley.

Court Transcript. Defendant John Shafer and his Amicus curae, Bruce Clark:

“CLARK: Yes. The position in law is that since there is no treaty for the area in question, the legislature of British Columbia does not have jurisdiction. For the same reason the legislature does not have jurisdiction, this court does not have jurisdiction, because this court derives its jurisdiction under the Supreme Court Act which emanates from that legislature, which itself doesn’t have jurisdiction. …So what essentially we have is this jurisdictional question is genuinely preliminary to everything else.”

“SHAFER: I’m a spokesperson for a native rights organization ca1led Concerned Citizens for Aboriginal Rights. It’s a group of 300 people in Victoria. All of my research and my readings indicated to me that there was — there was a major problem in the province concerning the fact that forest companies and third parties presumed to have the right to plunder unsurrendered native territory and I can see nowhere — in all my readings — I have yet to find a case where you will find an agreement between the native nations asking that Canada or BC rule over them.”

R. v. Gladstone, 1996

Supreme Court of Canada

Heiltsuk

“On or about the 28th day of April, 1988, at or near Vancouver in the Province of British Columbia, did unlawfully attempt to sell Herring Spawn on Kelp other than Herring Spawn on Kelp taken or collected under the authority of a Category J. Licence, contrary to Section 20 ( 3 ) of the Pacific Herring Fishery Regulation and did thereby commit an offence contrary to Section 6l ( 1 ) of the Fishery Act.”

Note – The judges of the BC Court of Appeal had widely differing reasons.

Ruling. BC Court of Appeal 1993, June 25.

Ruling. Supreme Court of Canada, 1996

Guerin v. The Queen, 1984

Supreme Court of Canada

Musqueam

In 1957, the Musqueam people surrendered 162 acres of their valuable Indian reserve lands in order to have the Indian Agent lease it on their behalf. The Agent, however, changed the terms of the lease in finalizing an agreement with the Shaughnessy Golf Club, including the amount of money to be paid for the rent.

Chief Delbert Guerin, and elected Councilors, filed for damages on behalf of Musqueam in 1975, and won the first case in 1979 at Federal Court. They were awarded $10 million in damages.

The government appealed, taking the position that the Indian Act forms a political obligation to Indigenous peoples generally – not a legal obligation; and that the conditions of the reserve surrender did not form a trustee relationship where the Crown was a trustee, in the private law sense, of the land in the reserve that was leased and whether the amendments to the lease itself were in breach of trust.

It is critical to note here that the Musqueam were specifically denied legal counsel to assist with negotiating the surrender and the lease, and they were denied access to the final lease agreement for about 13 years, almost the full 15-year period before the lease would come up for renewal.

The Federal Court of Appeal overthrew the lower court’s decision which found in favour of Musqueam, in 1982. Musqueam appealed.

The Supreme Court of Canada ruled, in 1984, that Section 18 of the Indian Act recognizes an obligation which “has its roots in the aboriginal title of Canada’s Indians as discussed in Calder v. Attorney General of British Columbia.”

The SCC ruled that federal government, here the Indian Agent, had a duty to act in the best interests of the Musqueam people, and, in order to fulfill that duty, the government Agent had to consult with them to find out what their interests were.

Ruling. Federal Court of Appeal, Dec. 1982

“…there was no breach of trust, that an action will not lie against the Crown for vicarious liability for breach of trust by servants of the Crown, that the respondents’ action is barred by the statute of limitations, and that relief should be refused on the ground of laches.

“For these reasons I would allow the appeal, set aside the judgment of the Trial Division and dismiss the respondents’ action, the whole with costs in this Court and in the Trial Division. The cross-appeal will be dismiss with costs.”

Ruling. Supreme Court of Canada, 1984.

“For these reasons, I would, with great respect to all who hold a contrary view, hesitate to resort to the more technical and far-reaching doctrines of the law of trusts and the concomitant law attaching to the fiduciary. The result is the same but, in my respectful view, the future application of the Act and the common law to native rights is much simpler under the doctrines of the law of agency.

I therefore share with my colleagues the conclusion that this appeal should be allowed with costs.

Appeal allowed with costs.

Case analysis and background.

Haida Nation v British Columbia (Minister of Forests; Attorney General), 2004

Ruling. BC Court of Appeal. 1997, November 7.

“The petitioners claim aboriginal title to a large area of British Columbia much of which is subject to tree farm licence no. 39 (T.F.L. 39) which was originally issued to the respondent MacMillan Bloedel in 1961.

“The preliminary issue of law is : whether the interest claimed by the Petitioners, namely aboriginal title, including ownership, title and other aboriginal rights over all of Haida Gwaii (the Queen Charlotte Islands), including the land, water, flora and fauna and resources thereof, is capable of constituting an encumbrance within the meaning of section 28 of the Forest Act.”

Ruling. BC Supreme Court 2000, November 21.

“The evidence establishes that in September 1998, the Province published updated “British Columbia Consultation Guidelines” governing consultation with Aboriginal peoples concerning their Aboriginal rights and title, for all provincial ministries. Although the guidelines state that “…staff must not explicitly or implicitly confirm the existence of Aboriginal title when consulting with First Nations,”…

Ruling. BC Court of Appeal. 2002, Feb 27.

Case analysis prepared for the Union of BC Municipalities by Bull, Housser & Tupper, Sept 2002

“The BC Court of Appeal delivered a landmark decision regarding the duty of the Crown and third parties to consult with First Nations who have asserted, but not proved, aboriginal rights or title. The order made by the Court was subsequently modified with supplemental reasons delivered on August 19, 2002.”

“The Court of Appeal made a declaration that the Province had in 2000, and the Province and Weyerhaeuser have now, legally enforceable duties to the Haida to consult with them in good faith.”

Ruling. Supreme Court of Canada. 2004

R. v. Jacobs, 1998

Sto:lo

“As the Sto:lo right to procure tobacco for religious, ceremonial and healing purposes has not

been extinguished, the next question is whether it has been interfered with such as to constitute a prima facie infringement of s. 35(1).”

Ruling. Supreme Court of BC, 1998, November 9.

R. v. Jack, 1975-80

Quw’utsun

“Eight Indians within the meaning of the Indian Act and registered members of the Cowichan Indian Band were charged …with salmon in their possession for food. The area where the fishing took place had been closed to all salmon fishing, under the BC Fishing Regulations. It was argued the Terms of Union of British Columbia and Canada had preserved aboriginal rights in Indians to fish for food at any time.

“Held, the accused were guilty. They were unable to show any treaty, statute or agreement having statutory effect conferring upon them the right, or any aboriginal right, to fish as they saw fit in contravention of the Regulations made under the Fisheries Act.” – 1975 decision.

Ruling. BC Provincial Court 1975. May 1.

Ruling. Supreme Court of Canada, 1980

R. v. Jim, 1921

BC Supreme Court

Chief Edward Jim of the North Saanich tribe was caught in possession of deer meat which he had hunted on his Reserve. in the appeal, the conviction of hunting in violation of the provincial Game Protection Act was overturned, since section 91(24) of the British North America Act means matters pertaining to Indians and lands reserved for Indians, is under federal jurisdiction. The judge decided hunting and fishing on reserves, Indian lands, should be regulated by the federal government. The federal government did regulate Aboriginal hunting in other provinces.

Kruger et al v. the Queen

Jacob Kruger and Robert Manuel were “non-treaty Indians” hunting outside the reservation for food in the traditional hunting area of the Penticton Indian Band, of which they were members. They had not applied for a provincial hunting license. That was in September of 1973.

This case was eventually decided in favour of the Province’s right to regulate hunting, and to exclude non-treaty Indians in British Columbia from hunting, except by the rules of the Wildlife Act.

Ruling. BC Court of Appeal, 1975

Ruling. Supreme Court of Canada, 1977, May 31

Case analysis: “Government, Two – Indians, One” Anthony Jordan, Nov. 1978 Osgoode Law Journal

MacMillan Bloedel Ltd. v. Michael Mullin -and- Moses Martin v. The Queen and MacMillan Bloedel Ltd.

Nuu-chah-nulth

Community leaders and protesters intervened to stop logging on Meares Island. Chief Moses Martin and Chief George Corbett put a case against the crown in motion for title of the island. They eventually won an injunction against the logging, and the case has remained adjourned since then.

Defense of Her Majesty The Queen, 1985 BC Court of Appeal:

Ruling. 1985 BC Court of Appeal, March 27.

“MacMillan Bloedel claims the right to log on Meares Island and says that the defendants unlawfully obstructed its employees when they went to the Island to survey and otherwise prepare for logging. The defendants in this action are the people who prevented MacMillan Bloedel from logging on Meares Island. One of them, Moses Martin, is an Indian. The rest can be described, I think accurately, as protestors.”

“The Plaintiffs’ claim is for a declaration that any authorization purporting to allow logging or to in any other manner interfere with said aboriginal title on Meares Island is ultra vires and of no force and effect. …The Indians wish to retain their culture on Meares Island as well as in urban museums.

The Indians have pressed their land claims in various ways for generations. The claims have not been dealt with and found invalid. They have not been dealt with at all. Meanwhile, the logger continues his steady march and the Indians see themselves retreating into a smaller and smaller area. They too have drawn the line at Meares Island. The Island has become a symbol of their claim to rights in the land.”

Nuchatlaht v. British Columbia 2023

May 11. BC Supreme Court

XII. Conclusion

[495] I conclude the plaintiff has not proved its claim for Aboriginal title to the overall

Claim Area.

[496] That said, when I outlined the areas of occupation, I frequently used the

language “near or adjacent to” reserves or accepted settlements. There may be

areas of sufficient occupation or use that are near the reserves or fee simple land

over which the plaintiff may be able to establish its claim to Aboriginal title. For

example, if there are CMT sites that are adjacent to a reserve, the plaintiff may have

a claim to them and the area between them and the reserve.

[497] However, the claim was not presented in that manner. I do not think it is open

to me to make more piecemeal declarations without hearing from the parties. And

even if that were open to me, I would not have the capability to do so without more

detailed maps showing precise locations along with further submissions.

[498] It may be that this case demonstrates the peculiar difficulties of a coastal

Aboriginal group meeting the current test for Aboriginal title, given the marine

orientation of the culture. For example, there will probably not be trails between one

coastal location and another, given that the means of transport was primarily by

canoe. This may be indicative of the need for a reconsideration of the test for

Aboriginal title as it relates to coastal First Nations. That would be for a higher court

to determine.

[499] If the plaintiff wishes to seek a declaration for smaller areas, it should set a

further hearing to canvass the procedure to be followed. I stress that I am not pre

judging any of the issues or whether a pleading amendment would be necessary. I

am merely leaving it open to the plaintiff to come back before me to canvass these

issues should it wish to do so. I ask that the plaintiff advise me of it’s position on this

within 14 days, or alternatively advise how much additional time it requires.

[500] If the plaintiff does not wish to advance this argument, the order will be that

the action is dismissed.

Oregon Jack Creek v CNR and Pasco v BCAG, 1985-2000

Nlaka’pamux, Secwepemc, Sto:lo

Ruling. BC Court of Appeal. 1985, August 19.

“This was an application by a native band for an interlocutory injunction restraining the C.N.R. from

proceeding with the construction of its twin tracking program along an eight mile stretch of the

Thompson River in the vicinity of the band’s reserve No. 5. In 1923 the C.N.R. was granted a right

of way through the band’s reserve No. 5 for railway right of way purposes. The right of way

subsequently was the subject of a Crown grant to the C.N.R. in 1924.”

Ruling. Supreme Court of Canada. 1989, November 7.

“The plaintiffs’ claim is for declarations, an injunction, and for damages based upon both aboriginal rights and more specific rights arising from the application of the Indian Act.

“Thirty-six Indian Chiefs commenced an action against the Canadian National Railway, alleging that the construction proposed by the C.N.R. in connection with a second track would involve rock fill

encroaching on several areas of the Thompson River bed and the dumping of rocks and gravel, adversely affecting the habitat of the fish in both the Thompson and Fraser Rivers. Each Chief commenced an action on behalf of himself and all other members of his Band. The application to the chambers judge was for leave to amend the style of cause and the statement of claim to advance a claim, not only on behalf of the members of each Band but also on behalf of the members of three Indian Nations. The action is framed as a personal one.”

Motion for a rehearing. Supreme Court of Canada, 1990.

Moved by CNR re Oregon Jack Creek v CNR 1989. Motion dismissed.

Paulette v. the Queen, 1973-77

Northwest Territories, Treaty 8

“In the matter of an application by Chief François Paulette et al. to lodge a certain Caveat with the Registrar of Titles of the Land Titles Office for the Northwest Territories.” 1973. Reasons for Judgement of the Honourable Mr. Justice W.G. Morrow, Supreme Court of the Northwest Territories:

Six weeks after the Calder decision in the Supreme Court of Canada, On March 24, 1973, sixteen Indian chiefs of the Northwest Territories claimed an interest in an area comprising some 400,000 square miles of land located in the western portion of the Territories, and presented a caveat for registration under the Land Titles Act. After nearly six months of legal procedures in the Supreme Court of the Northwest Territories, the Honourable Mr. Justice William G. Morrow ordered and adjudged on September 6, 1973:

1. I am satisfied that those who signed the Caveat are present-day descendants of those distinct Indian groups who, organized in societies and using the land as their forefathers had done for centuries, have since time immemorial used the land embraced by the caveat as theirs.

2. I am satisfied that those same indigenous people as mentioned in (1) above are prima facie owners of the lands covered by the caveat — that they have what is known as aboriginal rights.

3. That there exists a clear constitutional obligation on the part of the Canadian Government to protect the legal rights of the indigenous peoples in the area covered by the caveat.

4. That notwithstanding the language of the two Treaties [8 and 11] there is sufficient doubt on the facts that aboriginal title was extinguished that such claim for title should be permitted to be put forward by the caveators.

5. That the above purported claim for aboriginal rights constitutes an interest in land which can be protected by caveat under the Land Titles Act.

Paulette et al v. R. (1977) 2 S.C.R. 628

(1976) 2 W.W.R. 193 (NWT – Court of Appeal) Reversing 42 D.L.R. (3d) 8

Related proceedings (1973) 39 D.L.R. (3d) 81 (Fed. Crt.)

The Attorney General of Canada intervened in this case, suing Judge Morrow of the original NWT court. An injunction against Morrow was created, that he could no longer have anything to do with the case.

Finally in the Supreme Court of Canada, with a full bench of nine judges, the court ruled simply that there was no instrument in the existing Lands Act of the Northwest Territories that could accommodate the caveat requested by the Chiefs. The case was dismissed.

R. v. Sparrow, 1984-1990

Musqueam

“The appellant, Mr. Sparrow, a member of the Musqueam Indian Band, was apprehended on March 30th, 1984, fishing with a 45 fathom net in Canoe Passage, part of the Fraser River Estuary which is within Musqueam tribal territory.

He was fishing under the Band’s Food Fishery License, which permitted the use of drift nets not exceeding 25 fathoms in length.”

1985 County Court ruling, Vancouver 1985, December 20.

Case comment by Ratcliffe and Co., prepared for the BC Aboriginal Peoples Fisheries Commission, 1986, October.

Factum of the Attorney General of British Columbia, 1986. On appeal to the BC Court of Appeal.

“The issue for determination in this case, like Derriksan, supra, and R. v. Kruger and Manuel, is not

the existence or extinguishment of aboriginal rights, but the extent to which such rights, if they exist, may be subject to regulation.”

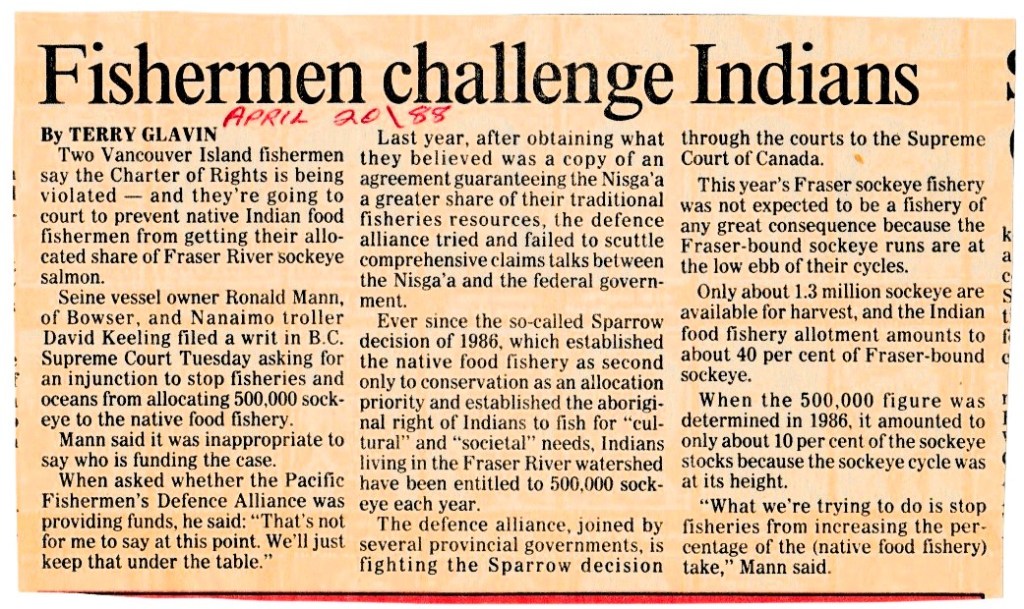

1988 News re. the 1985 decision:

Ruling. Supreme Court of Canada, 1990, May 31.

“The appeal and cross-appeal are dismissed. The constitutional question should be sent back to trial to be answered according to the analysis set out in these reasons.”

The Musqueam right to take salmon for food was judicially recognized. They were the only other Indigenous group to have this recognition, other than those with 1850-54 treaties on Vancouver Island.

R. v. Smokehouse, 1996

Sheshaht and Opetchesaht

Ruling made simultaneously with R. v. van derPeet and R v. Gladstone, in a trilogy decimating fishing rights and reversing the previously established burden on the crown to prove that they had “extinguished” an Aboriginal right; shifting that burden to Aboriginal parties to prove they had such a right at the time of the British crown’s assertion of sovereignty – about 1846.

Ruling. Supreme Court of Canada, 1996.

“Case law on treaty and aboriginal rights relating to trade supports the making of a distinction between the sale, trade and barter of fish for, on the one hand, livelihood, support and sustenance purposes and for, on the other, purely commercial purposes. The delineation of aboriginal rights must be viewed on a

continuum.

“The facts did not support framing the issue in terms of commercial fishing.”

Skeetchestn v BC (Registrar of Land titles), 2000

Secwepemc

Ruling. BC Supreme Court. January 20, 2000.

“The appellant Indian Band appealed from two decisions of the Registrar of Land Titles refusing to register first, a certificate of pending litigation and second, a caveat. Both appeals pertain to an Aboriginal title claim made by the Band against approximately 1000 acres of land known as the 6 Mile Ranch.”

Action dismissed.

Taku River Tlingit v. Redfern 2002

Case summary of the BC Court of Appeal ruling, 2002. Prepared by Pape and Salter.

“This is another wonderful victory for the Taku River Tlingits. It affirms the decision of the Supreme Court of British Columbia that set aside the Project Approval Certificate granted to Redfern. lt also fully supports one of the major arguments that the Taku River Tlingits put forward – that the government has fiduciary duties towards Aboriginal people when it is making decisions that will affect their way of life or Aboriginal rights.”

Ruling. Supreme Court of Canada, 2004.

Thomas v. Rio Tinto Alcan Inc.

Saik’uz and Stellat’en

Ruling. BC Court of Appeal. 2024, February 26.

“Remedy on appeal:

- The plaintiffs have an Aboriginal right, as claimed, to fish for food, social, and ceremonial purposes in the Nechako River watershed; and,

- As an incident to the honour of the Crown, both the provincial and federal governments have an obligation to protect that Aboriginal right.”

Tsilhqot’in Nation v. British Columbia (Minister of Forests) 1989-2014

The first ever declaration of Aboriginal title on the ground was made 41 years after Calder, in Tsilhqot’in. The Tsilhqot’in established Aboriginal title in the Xeni Gwetin community’s claim area. The court undertook substantial developments in describing Aboriginal title.

Beginning in 1989 as litigation to stop logging in the Brittany Triangle, Chief Roger William of Xeni Gwetin was the name plaintiff for the community. The “William” case continued to the Supreme Court of BC in 2007, where Justice Vickers made a ruling which identified “Aboriginal title” as encompassing large tracts of land, and not just site-specific ‘postage stamp title’ such as fishing spots and hunting blinds. The BC Court of Appeal threatened to retreat from that position, but it was upheld in the Supreme Court of Canada in 2014.

Ruling Supreme Court of Canada 2014

Appellants Factum (Tsilhqot’in; Xeni Gwetin) Supreme Court of Canada 2013

Respondents Factum (Her Majesty the Queen) Supreme Court of Canada 2013

Commentary on Tsilhqot’in Nation v. BC, SCC 2014, by First Peoples Law; Center for Constitutional Studies;

Osler Law Group; Legislative Assembly of BC; Can Lii Connects

Ruling BC Supreme Court 2007

Press Release 2007 by Tsilhqot’in counsel, Woodward and Company

UUKW ET AL. v. THE QUEEN ET AL.; MARTIN ET AL. V. THE QUEEN ET AL.; PASCO ET AL. v. CANADIAN NATIONAL RAILWAY COMPANY ET AL.

Ruling on procedure. BC Court of Appeal. 1986, July 22.

The plaintiffs in each of the these actions appealed from the pre-trial order of Chief Justice

McEachern (reported supra, p.146) wherein he held, inter alia, that the three actions be tried together and by the same judge.

“The Chief Justice had not been informed that the factual foundation in respect of aboriginal title was not the same in each of the three actions. Aboriginal title must be determined on a case-by-case basis.”

Wewaykum v. Canada

Memo re. the crown’s position on when Indian Reserves in BC were made. 1988

“It is fundamental to our defence in Roberts that the two reserves in question be determined by the Court to have been allocated to the Cape Mudge Band prior to 1900. On the other hand, the interests of the Crown in the Gitksan Carrier and Pasco actions would no doubt be better served by a ruling that reserves in British Columbia were not created until at least 1930 because there will then be available a stronger argument that provincial legislation has effectively extinguished certain aboriginal rights insofar as reserve lands are concerned.” February 3, 1988

Rulings:

West Moberly v. BC, (Ministry of Energy, Mines and Petroleum Resources)

Ruling. BC Court of Appeal, 2011, May 25.

“Appeal by the province from an order declaring it in breach of its duties to consult and accommodate West Moberly First Nations concerning decisions made by government officials at the request of First Coal. Two of the decisions amended existing permits to allow First Coal to obtain a 50,000 tonne bulk sample of coal and to engage in a 173-drill hole, five-trench Advanced Exploration Program. The third decision permitted First Coal to cut and clear up to 41 hectares of woodlands to facilitate the Advanced Exploration Program. First Coal’s proposed exploration activities were located 50 km from the Moberly Lake Reserve, within a traditional hunting area.”

The province “based its concept of consultation on the premise that the exploration projects should proceed and that some sort of mitigation plan would suffice. However, to commence consultation on that basis does not recognize the full range of possible outcomes, and amounts to nothing more than an opportunity for the First Nations “to blow off steam”.”

R. v. White and Bob

Snuneymuxw

Clifford White and David Bob were charged under the BC Game Act, for having six deer in their possession, fourteen days after the close of hunting season. They were convicted by a Magistrate on September 25, 1963, and each ordered to pay $103, or serve forty days in jail.

The men were both Snuneymuxw citizens, who had sold land to Governor James Douglas in 1854, and reserved certain rights, in a treaty. Their hunting rights had been preserved there against change.

The men retained legal counsel – Tom Berger of the Thomas Hurley firm, and appealed in County Court. They were acquitted March 4, 1964. The reason for their acquittal was twofold: “prohibitions of the Game Act, against the hunting of deer during the closed season, do not apply to native Indians, descendants of certain Nanaimo tribes, who hunt on unoccupied lands in an organized district, such lands not being within a reserve but being lands conveyed to the Hudson’s Bay Co. by ancestors in the tribes.

The BC government appealed the ruling that confirmed the Nanaimo treaty rights, or the aboriginal hunting rights, and released Messrs. White and Bob. The BC Court of Appeal dismissed the government’s appeal on December 15, 1964.

The Province then appealed directly to the Supreme Court of Canada, which granted them leave to appeal, on April 5, 1965, on the following questions of law:

Was the operation of the Game Act, in the circumstances of the charge, excluded

a) by reason of the existence of a treaty within the meaning of Section 87 of the Indian Act, or

b) by reason of aboriginal hunting rights enjoyed by the Respondents and recognized by a Royal proclamation issued in 1763 and otherwise?

Ruling. BC Court of Appeal, 1964

Ruling. Supreme Court of Canada, 1965

Respondents Factum (White and Bob) to Supreme Court of Canada, on appeal from the BC Supreme Court.

Yahey v. British Columbia, 2021

Blueberry River First Nation, Treaty 8

Ruling. BC Supreme Court, June 29, 2021.

“The Plaintiffs submit that a number of key species are in decline within the Claim Area, most notably caribou, moose, and furbearers, including marten and fisher. They submit that industrial development within the Blueberry Claim Area has either caused or contributed to these declines.”

[1879] As Blueberry puts it in their reply submissions: “This is not a case where there is a single mechanism, or law that infringes the right – it is the cumulative effect of oil and gas and forestry authorizations in the context of existing private land, agricultural and hydro-electric authorizations, which result in the infringement…” Blueberry adds that it is the “accumulated effects of the discretionary decision-making” under various statutes that it says has led to the unjustified infringement of its rights. I agree.

[1880] I have concluded that the provincial regulatory regimes do not adequately consider treaty rights or the cumulative effects of industrial development.

Declarations

1984

Significance of Indian Consent UBCIC 1984

Regarding the patriation of the Canadian Constitution and the mandated First Ministers Conferences

Excerpt: What we must ask ourselves in 1983 is why is Canada sitting down with the Indian people in spite of the powerful Position she seemingly has. Looking at the Royal Proclamation and the Constitutional Accord, both these documents were forced by Indian Nations.

The problem for the Indian Nations is that the Land Claims Process is still the most active policy of Canada to obtain our consent for extinguishment of title. Once we agree to this process, participate in it and sign an agreement, we have strengthened Canada’s belief that this is the route to go and give her the incentive to pursue this Policy with increased vigour. So far the Indian Nations have participated in negotiations through this process, but Canada cannot yet point to any Indian Nation’s consent for Canadian ownership of the land. Once she has achieved consent even if it is Nation by Nation and not all at once, she will have met international standards for acquiring right to occupancy and title to land. This is the leverage of the Indian Nations in 1983.

… What do we do now? What are we prepared to negotiate and on what basis will we legitimize this process? Will we, for example, negotiate to be a part of Canada’s Constitution or do we negotiate the same terms of the Royal Proclamation of 1763?

For Indian Self-Government to be entrenched and demonstrate Indian consent, Canada must develop negotiations with the Indian Nations and somehow at the end of it show Indian Nations agreeing to the legislation. What is the form this will take?

1984

World Council of Indigenous Peoples

Declaration of Principles

RATIFIED BY THE 4th GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF THE WORLD COUNCIL OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLES, PANAMA, SEPTEMBER 23-30, 1984

1. All human rights of indigenous people must be respected. No form of discrimination against indigenous people shall be allowed.

2. All indigenous peoples have the right to self-determination. By virtue of this right they can freely determine their political, economic, social, religious and cultural development, in agreement with the principles stated in this declaration.

3. Every nation-state within which indigenous peoples live shall recognize the population, territory and institutions belonging to said peoples.

1988

Universal Human Rights – Aboriginal Dialogue

Conference by United Native Nations, AMSSA, UBCIC, BC Human Rights Coalition, Gitksan and Wet’suwet’en Tribal Council, May 27-29

Featuring transcripts of presentations by Rosalee Tizya, UBCIC secretary; Chief Don Ryan, Gitksan-Wet’suwet’en Tribal Council President; Chief Ron Ignace, Skeetchestn of Secwepemc; Lavina White, Haida; Chief Ruby Dunstan, Lytton of Nlaka’pamux; George Watts, Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council; Professor Michael Jackson, UBC school of Law.

1993

1993 Draft Universal Declaration on Rights of Indigenous Peoples

The UNDRIP went through several incarnations. It started as a project of the Working Group on Indigenous Populations. That Working Group became the Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, and the PFII brought the UNDRIP to completion. The Draft below was produced during the WGIP days.

The doc below is a screenshot of a UN ECOSOC page. It gives a background on the development of the WGIP and UNPFII.

1994 Study on Treaties and other Constructive Arrangements between Indigenous Peoples and States.

SOVEREIGNTY PEOPLES INFORMATION NETWORK 1994

Lawrence Pootlass, Headchief NUXALK NATION (The House of Smayusta)

William Ignace SCEWEPMEC NATION

Harriet Nahanee PATCHEEDHT NATION

Lavina White HAIDA GWAII NATION

James Louie LIL’WAT NATION

Glen Douglas, Jeannette Armstrong, Bob Campbell SUKINAKAIN NATION

Pierre Kruger SINIXT

Delegation to meet with and present written submission to

Alfonso Rodriguez Martinez, member of the Working Group on Indigenous Populations, Special Rapporteur for the Study on Treaties and other Constructive Arrangements between Indigenous Peoples and States. In Seattle, Washington September 1994

1997 Confederated Native Court v. Canada and USA

IN THE MATTER OF court jurisdiction under natural law in and over the unceded Indian territories of the Hudson, St. Croix, Chaleur Bay, Ottawa and lower St. Lawrence River Drainage Basins and Estuaries;

AND IN THE MATTER OF court jurisdiction under international and constitutional law’s confirmation of natural law pursuant to Magna Carta, 1215, Sublimus Deus, 1537, Statute of Frauds, 1670, Mohegan Indians v. Connecticut, 1704, Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, 1831, Regina v. Cadien, 1838, and the Convention for the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, 1948.

MOHEGAN COURT, PASSAMAQUODDY COURT, MI’GMAQ COURT AND ALGONQUIN COURT

Excerpt: UPON TAKING judicial notice of the suppression and genocide of the native people caused by the prematurely assumed jurisdiction of the newcomer courts, and in accordance with the accompanying reasons for judgment, this native court declares:

1. Court jurisdiction prima facie territorially is vested in the native courts and precluded from the newcomer courts; and …

2006 APPLICATION FOR A CONSTITUTIONAL DECLARATION OF JURISDICTIONAL LAW ALONE

Tthowgwelth and Toanunck, Applicants, versus

Supreme Court of Canada and Supreme Court of the United States, Respondents.

To prevent the genocide-in-progress in North America from continuing contrary to Article 2(b) of the Convention for the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, 1948, in virtue of the Respondents’ judicial inactivity refusing to address the Constitution Ac| 1867, $109 and the Constitution, 1789, Article l, $2,12, clause l.

Note: the attached motion was subsequently filed in New York, USA, and Valletta, Malta.

2010 “Fight for Our Rights”

Solutions Based on Indigenous Inherent Rights

Prepared for Kukpi7 Wayne Christian for the Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs Annual General Assembly, September 15, 2010

Excerpt:

Our indigenous knowledges are critical for all humanity and this will come to light through

our abilities to renew alliances formed by our ancestors or create new alliances to meet the

pressures of today. We propose the following solutions for “fanning the embers of our

Allied Nations”:

- Convene Indigenous Peoples and Nations to discuss alternatives based on existing

or new political alliances and protocols; - Learn from our alliances in the past such as the efforts put forth by the Allied Tribes;

- Develop coalitions with others that respect our inherent jurisdiction, right to self‐

determination as peoples, and need for constitutional, law and policy reform; and - Peace Making between Indigenous Peoples based on our Indigenous laws and

protocols and indigenous treaties to address issues between our Peoples and build

stronger Indigenous Alliances

Inter-American Court of Human Rights

Organization of American States, Americas regional forum of the United Nations

Lil’wat presentation at UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, 2011

Re. the Lil’wat Petition to IACHR: “Canada has no jurisdiction” (Edmonds v. Canada, Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, 2007)

2009

HUL’QUMI’NUM TREATY GROUP v. CANADA

Report on Admissibility October 30, 2009

2014

Edmonds v. Canada

Report on Admissibility by the IACHR